Three quarters of high school students say they would like to stay in their town if they could find a well-paying job there. Yet a majority of them head off to college after graduation, not aware that Greater Minnesota is well positioned to provide students with the jobs they are interested in and passionate about. It’s time to change that.

By Luke Greiner, Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development

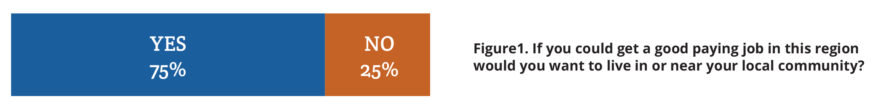

The perceptions of rural youth matter, particularly how they perceive their local communities and the economic opportunities that await them after graduating high school or college. Given the narrative and statistics we usually hear, it may be surprising to know that students say they would favor staying in their local communities if they were able to secure a “good paying job.” Seventy-five percent of students surveyed in southwest Minnesota indicated they would stay in their local area if they had an acceptable job prospect (see Figure 1).

That so many youth in rural areas would prefer to stay in rural areas is excellent news for rural communities and companies. The challenge, though, is educating students and parents about the real opportunities that exist right in their local economy. What happens when a student goes off to college and comes back to find that relatively few jobs require college? Does the wage they are willing to work for change after the investment of higher education?

Because most rural areas haven’t been able to count on an in-flow of new residents to increase the workforce in their communities, the employers of Greater Minnesota depend largely on residents who are already living there, especially a steady flow of students out of local high schools. This is especially true in counties where, despite still having more births than deaths, they have had a steady population loss since the 1950s due to out-migration.

Using survey data from DEED’s participation in the Southwest Minnesota Career Expo, we can gain valuable insight into the perceptions of the next generation of workers. The survey is offered annually to roughly 2,000 tenth-grade students in southwestern Minnesota. It’s likely that the views of these students and who influences them are similar for students across Minnesota.

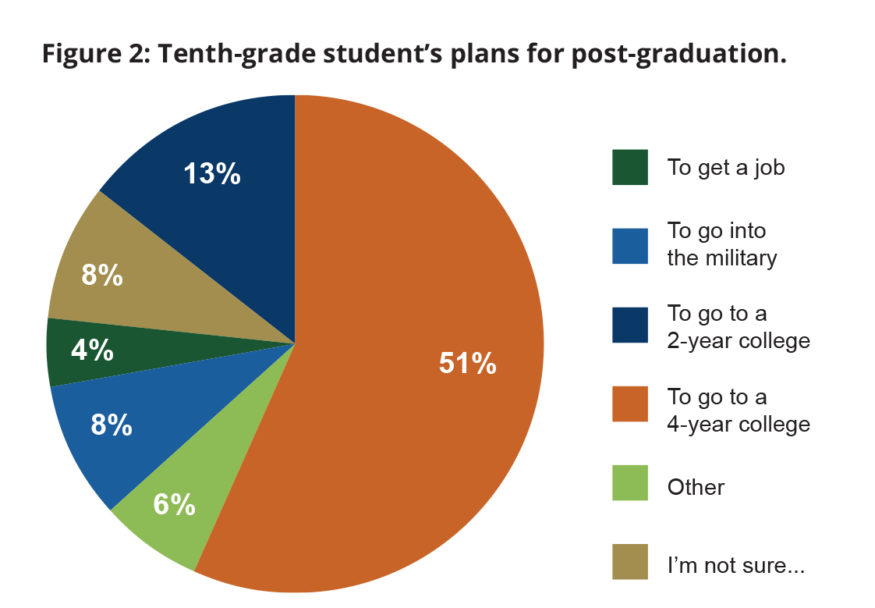

When tenth-grade students were asked what their plans were after high school:

- 61% indicated that they plan to go to a university.

- Almost one in twelve said they plan to go into the military, yet statistics show that only about one in one hundred actually do.

- Only 6% planned to join the workforce right after high school, yet the state’s longitudinal education data show that 26% actually end up doing so.

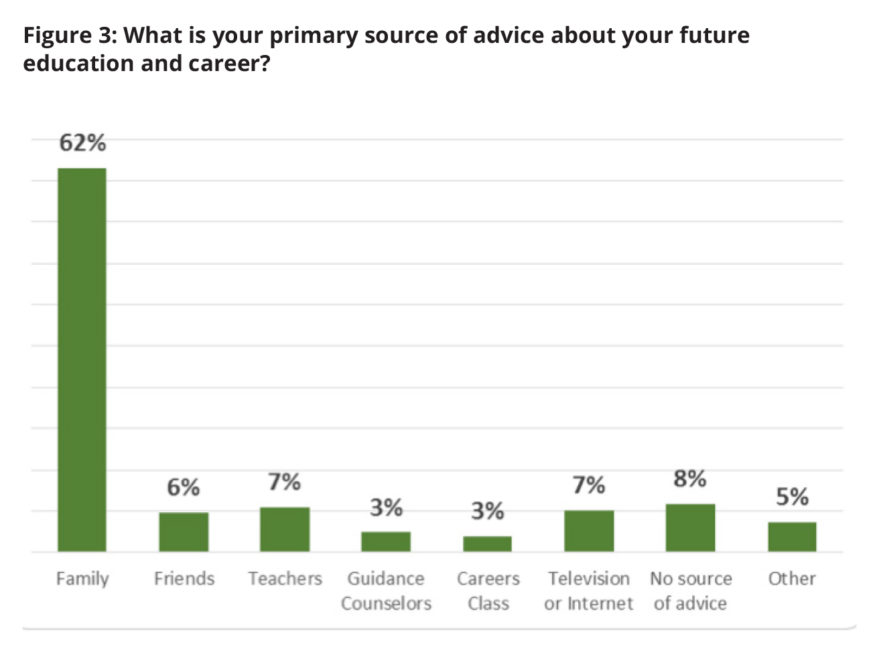

There are many factors that students consider when deciding on their future education or career path, but one influencer really stands out: their parents.

Figure 3 shows how nearly two thirds of students are relying on family to help inform their education and career decisions. This strong correlation between family (parents’) guidance and student plans highlights a possible disconnect between actual opportunities that exist in Greater Minnesota and what parents think is the best way for their child to achieve success.

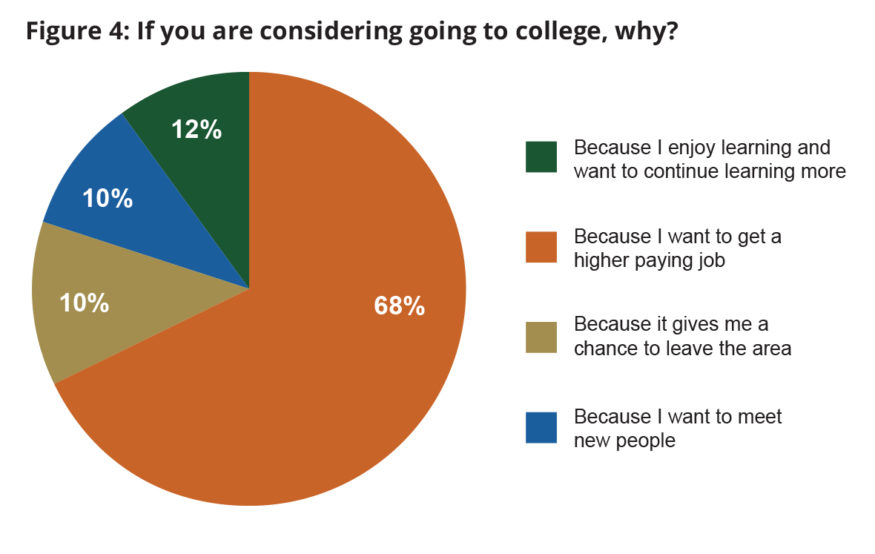

Enrolling in college can be an excellent way to achieve a successful career, and clearly students (by way of parents) also strongly perceive college as a way to get a higher paying job.

Two thirds of students who responded said they were primarily interested in college to boost their earning potential. It’s likely that this response reflects their parent’s views on the benefits or necessity of college to get a good job (see Figure 4).

Make no mistake, the data clearly support numerous benefits of college that many graduates enjoy. Enrolling in college, particularly a four-year institution, however, is not the only or best option for every student.

Roughly 69 percent of jobs in Greater Minnesota do not require education beyond a high school diploma. A significant number of these jobs are in entry-level occupations with low pay and low or no educational requirements. For many new workers, though, these entry-level jobs represent the first step in gaining valuable skills that enable upward progression to better, higher paying jobs. Furthermore, Minnesota has roughly 230,000 jobs with a median annual wage greater than $50,000/year that do not require college. And employment projections for future jobs show similar educational demands, meaning that in at least the next decade we shouldn’t expect this to change.

Lack of college is also not always synonymous with low skill. Many of the well-paying jobs in Greater Minnesota that typically do not require any type of higher education do require a specific skillset gained through apprenticeships or on-the-job training.

With so many students planning on going to college and relatively few jobs requiring it, it seems reasonable to suspect that well-intentioned parents might be overlooking excellent opportunities right in their own backyard that could possibly lead to a successful career for their student. Rural Minnesota has excellent jobs for workers of every educational background, something for everyone if you will, but communities miss out when the perception is that only a sliver of the jobs in the area are deemed “good.”

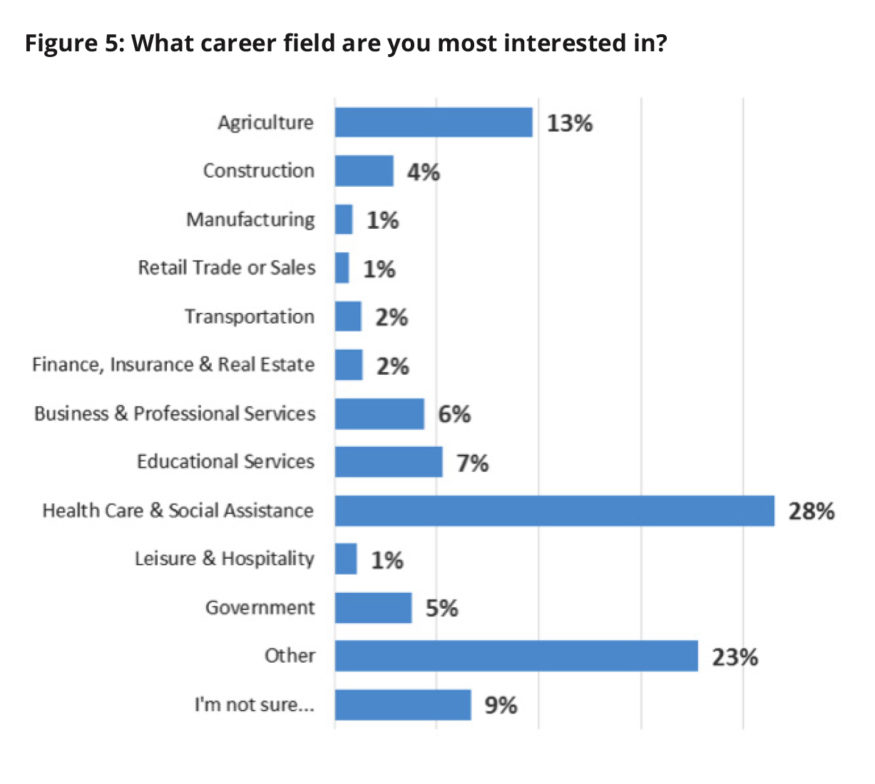

Greater Minnesota is well positioned to provide students with the jobs they are interested in and passionate about. Over one-quarter of students indicated that they were interested in health care and social assistance, which happens to be the largest employing industry in Greater Minnesota, representing 19% of all jobs. There is also an abundance of highly in-demand agriculture jobs that have high wages and low educational requirements in many rural areas. Getting Greater Minnesota youth to better understand the best path to the jobs they are interested in can help businesses attract talented employees and help students better prepare for the job they desire.

So how well do the plans of tenth-grade high school students in Greater Minnesota represent what high school graduates actually end up doing?

With a full two-and-a-half years left of high school at the time of the survey, it’s no surprise that many students do end up changing their minds and pursuing other paths after high school. Looking back at how the class of 2016 enrolled in higher education in the fall after graduating high school:

- 27% enrolled at a four-year school

- 23% enrolled at a two-year school

- 17% enrolled in higher education outside of Minnesota.

- 26% started working without enrolling in higher education (class of 2015)

We know that over a quarter of high school graduates join the workforce after high school without any higher education. This is problematic not because they aren’t going to any college, but rather because it’s possible they haven’t been preparing for the vast majority of jobs that require nothing more than a high school diploma but do require skills. Only 6% of tenth-grade students indicated in the surveys that they plan to join the labor force after completing high school. If that’s the case, how well do those who changed their plans from going to college to not going to college know the labor market or what skills employers are looking for?

Again, just because a particular job doesn’t require college doesn’t automatically mean it’s low-skilled and low pay either. Not everyone is qualified for these jobs. Becoming successful without college in Greater Minnesota takes careful and intentional planning to become successful, just like it does for college.

Success rates for Greater Minnesota’s students and the regional economies across rural Minnesota can improve by aligning educational programing to economic demand. How students perceive their own local community and the job opportunities it has for them is critical to retaining and attracting qualified workers. With record numbers of job openings and a declining labor force in many rural counties, Greater Minnesota can’t afford the misperception of its economic opportunities.

Luke Greiner is DEED’s regional analyst for central and southwestern Minnesota.