Changing the story on careers in rural Minnesota

For decades, the narrative speaking to rural high school students has been that to succeed, they must leave. But what if we could do something about that?

August 2019

By Kelly Asche, Research Associate

For a printable version, click here.

All Articles in this Series:

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 1 – the data

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 2 – resident recruitment

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 3 – engaging populations with high barriers to employment

Check out our explainer video, “Why do we have a rural workforce shortage” for a quick overview of this research.

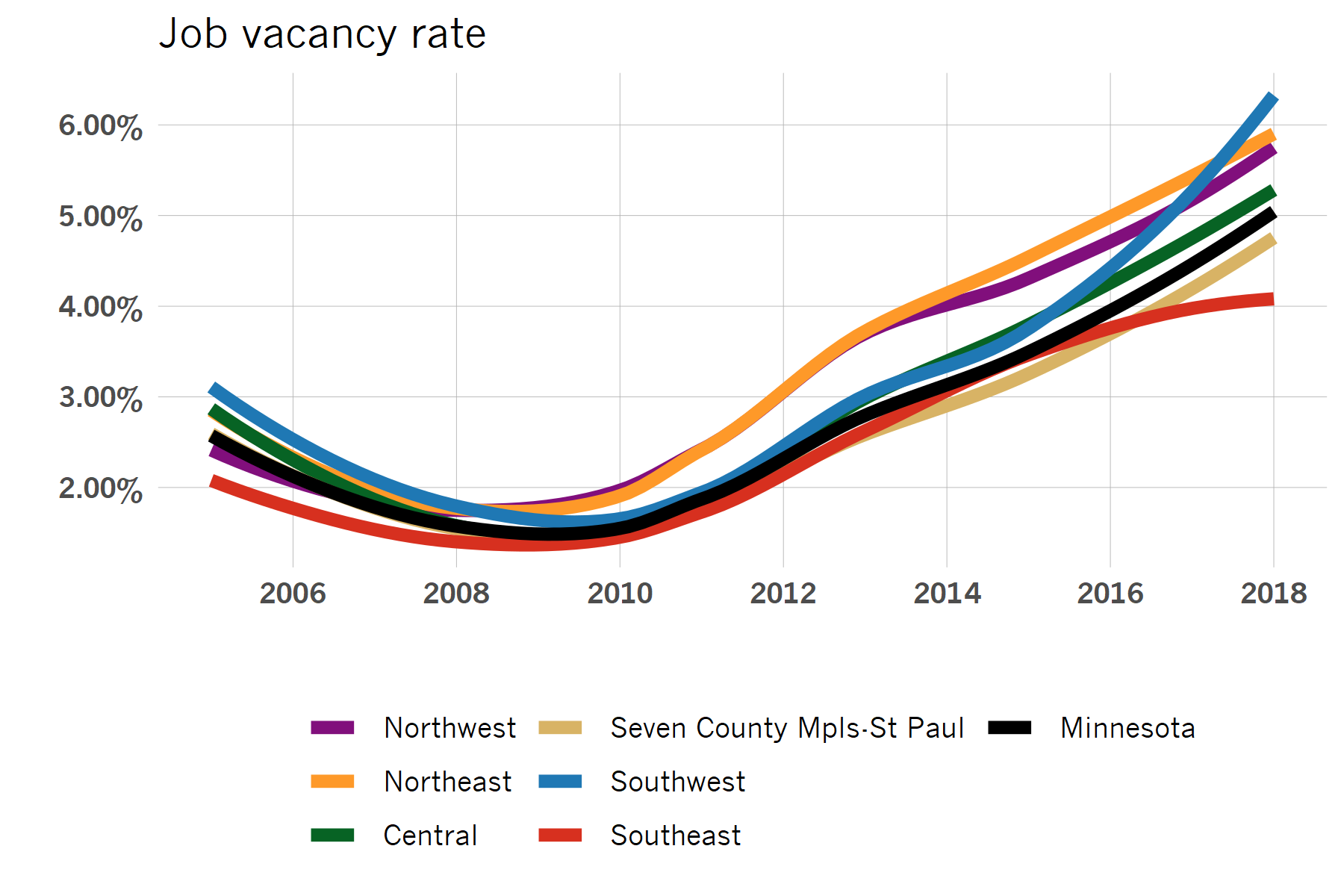

As the demand for workers increases in Greater Minnesota, employers and workforce development organizations are increasingly examining why so many young people leave rural regions after high school despite growing local opportunity. In part 1 of our research this year on the workforce shortage, we highlighted the growing number of job vacancies in Greater Minnesota (Figure 1).

Business owners and economic developers are scrambling harder than ever to find workers to avoid cutting production. Jessica Miller, a regional workforce strategy consultant for the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED), sees the challenge employers are up against, not only to attract workers into their regions, but also to keep the high school students already there from leaving.

“Businesses and organizations have started to take notice of the high school narrative that [says] there are no opportunities for them in their region.”

To combat this narrative, employers and regional organizations are working together to open high school students’ eyes to a world they may have never before considered.

The real influencers in students’ lives

The long-held perception among students in rural areas that to get ahead after high school, they must move away is no surprise to rural residents.

What is surprising is that according to research, most students, given the choice, would prefer to live in their hometown or at least their home region—if they thought they could.

So where does this idea come from, that youth must leave their rural communities in order to succeed? There has been a large amount of research on just this question over the years. It appears to come down to a handful of primary influencers: immediate family, formal advisors, and experience.

A strong influence that’s often overlooked comes from family, and in particular, parents. Despite what parents may think, they have a significant amount of influence over their teenagers’ decisions, especially when it comes to their futures. As a result, the value that parents in rural areas place on attaining a higher education degree combined with what they believe to be a lack of economic opportunities greatly increases the likelihood that the child will leave (Kirkpatrick, Elder, & Stern, 2005).

Employers and organizations in Minnesota are finding this out firsthand. According to Miller, from DEED, when AGCO, a worldwide farm implement manufacturer in Jackson, MN, hosted students in their facilities, their goal was to highlight the sophistication of their manufacturing process and to overcome the common misperception that their industry was dirty. The AGCO hosts quickly realized, though, that although the students were excited about the possibilities, their parents, who weren’t on the tour, were not. So they shifted their strategy to bring in parents with the students so they can see it for themselves, together.

Another source of influence in students’ perceptions are formal advisors—teachers, guidance counselors and college admissions officials. Although these individuals typically have less influence on a student’s perceptions of local and regional opportunities, they can play a significant role in how parents perceive opportunities for their children. One study showed that guidance counselors, college admissions officials and teachers ended up making a compelling case for kids going elsewhere for higher education when they discussed the decline of the rural economy with parents. More employment possibilities, better pay, and greater flexibility appeared to resonate strongly with parents, especially with rural parents of first-generation college-goers (Tieken, 2016).

The strongest influencers on students are hands-on experiences that let them see actual careers, allowing them to imagine themselves in those jobs and giving them concrete ideas to aspire toward. According to a study out of Pennsylvania State University, “Youth who believed that there are enough jobs here for those who want them and who like their current community were less likely to identify aspirations of living in another place or to be uncertain of their residential aspirations” (McLaughlin, Shoff, & Demi, 2014).

This idea is confirmed by folks on the ground.

“When we conduct our ‘get-to-know-you’ survey at the beginning of the year,” says Tyler Gehrking, facilitator for the Kandiyohi County Creating Entrepreneurial Opportunities (CEO) program, “90% of the students reported that they don’t see themselves living here, but by the end of the program, the statistics are the complete opposite.”

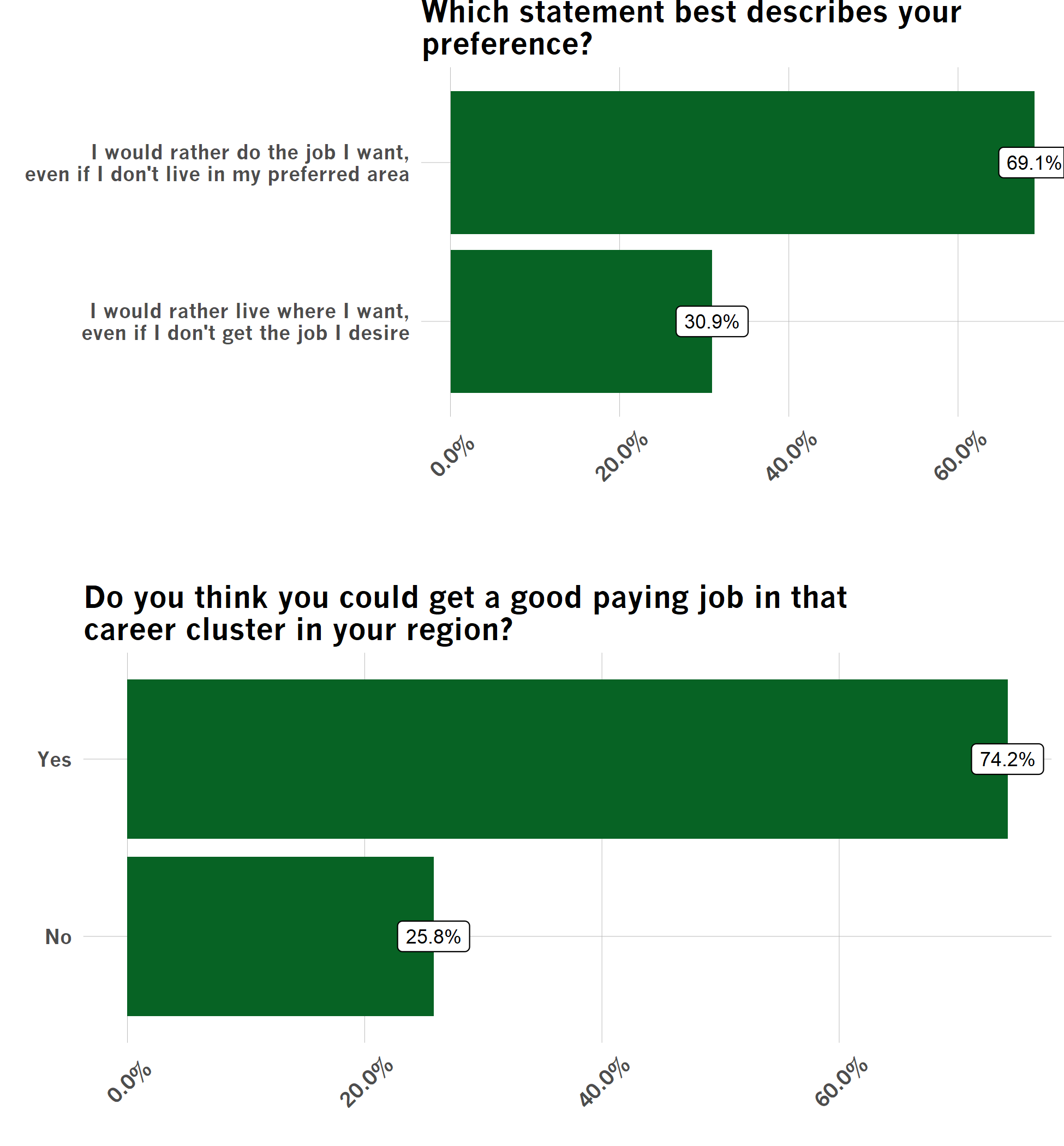

With all of these sources of influence, what do students in Minnesota actually think? Luke Greiner, a labor market analyst for DEED, was able to extract a snapshot of what students were thinking about in terms of their career interests, residential preferences, and whether they believed that they could find opportunities in their desired careers. In the fall of 2018, they surveyed over 700 tenth-graders from southwest Minnesota and found that although a majority of students (70%) said they would choose the career they wanted over living in the place they preferred, 74.2% of the students also believed they could find a well-paying job in their desired career field in the region (Figure 2). (Check out Labor Analyst Luke Greiner’s blog post providing all of the results from the survey.)

Figure 2: Nearly 70% of over 700 high school students from southwest Minnesota said they would choose a job they want over living where they want. Luckily, 74% of the students also believed they could find a well-paying job in their desired career in the region. Source: MN DEED Student Survey, Southwest Career Expo in Worthington and Marshall

The fact that so many students believe they can find a well-paying job in the region is encouraging for all of Greater Minnesota. It means that students aren’t necessarily buying into the dominant narrative that they have to leave to have the career they want. As demographic research suggests, this snapshot doesn’t mean the trend of losing young people after graduation is going to reverse completely, and there are many forces at work to influence students’ lives. However, these statistics do indicate that the efforts to change the perceptions held by students and their parents is, at the very least, planting a seed.

A resurgence in engaging youth in Greater Minnesota of local opportunities

Convincing students to live and work in a place they’ve been told they’re better off leaving requires collaboration among many players. Employers, workforce development organizations, school districts, higher education institutions, local, regional, and state government agencies and other non-profits are all committing to these efforts in Greater Minnesota.

One of the more significant developments over the last few years discussed by folks in the field is engagement and support from area businesses and employers.

“Businesses have recognized the need to touch base with students much earlier than after they graduate high school,” says Tyler Gehrking, facilitator for the Kandiyohi County CEO Program.

Creating Entrepreneurial Opportunities focuses on entrepreneurial thinking, teaching students not just how to think creatively, but how to put that to work by starting their own businesses. Versions of the program have been developed in Kandiyohi County, the Staples-Motley, Wadena-Deer Creek and Pillager school districts, and the Wright Center in Buffalo. Students are mentored by local business owners, tour various employers in the region, and learn important people skills that aren’t typically taught in school. By the end of the year, students have started their own businesses and are getting a sense of the work and leadership needed to sustain them.

Employers in turn aren’t just engaged with the students, they also underwrite the costs for the program. In the Brainerd-Central Lakes area, regional restaurants and resorts have developed the ProStart program in area high schools, providing the expertise and financial resources to address their shortage of staff for positions from chefs to restaurant managers. The program consists of a two-year curriculum teaching culinary techniques and management skills, providing real-life experience working in area restaurants.

Minnesota used to have over sixty career and technical programs. Now, after years of shutting them down, they’re experiencing a resurgence in Greater Minnesota. LYFT Pathways is an initiative in southwest Minnesota funded by the state legislature to provide technical assistance, facilitation, and grants to build programs where at least two school districts and one business are working together to develop curriculum around skills needed for a specific industry that has been identified as “in need.”

“Vocational education used to be a big thing in schools,” says Tom Hoff, Career and Technical Project Coordinator for LYFT Pathways. “Over the past thirty years, it has been dismantled, especially in small schools. But there is definitely a lot more conversation and interest in providing this type of education for students.”

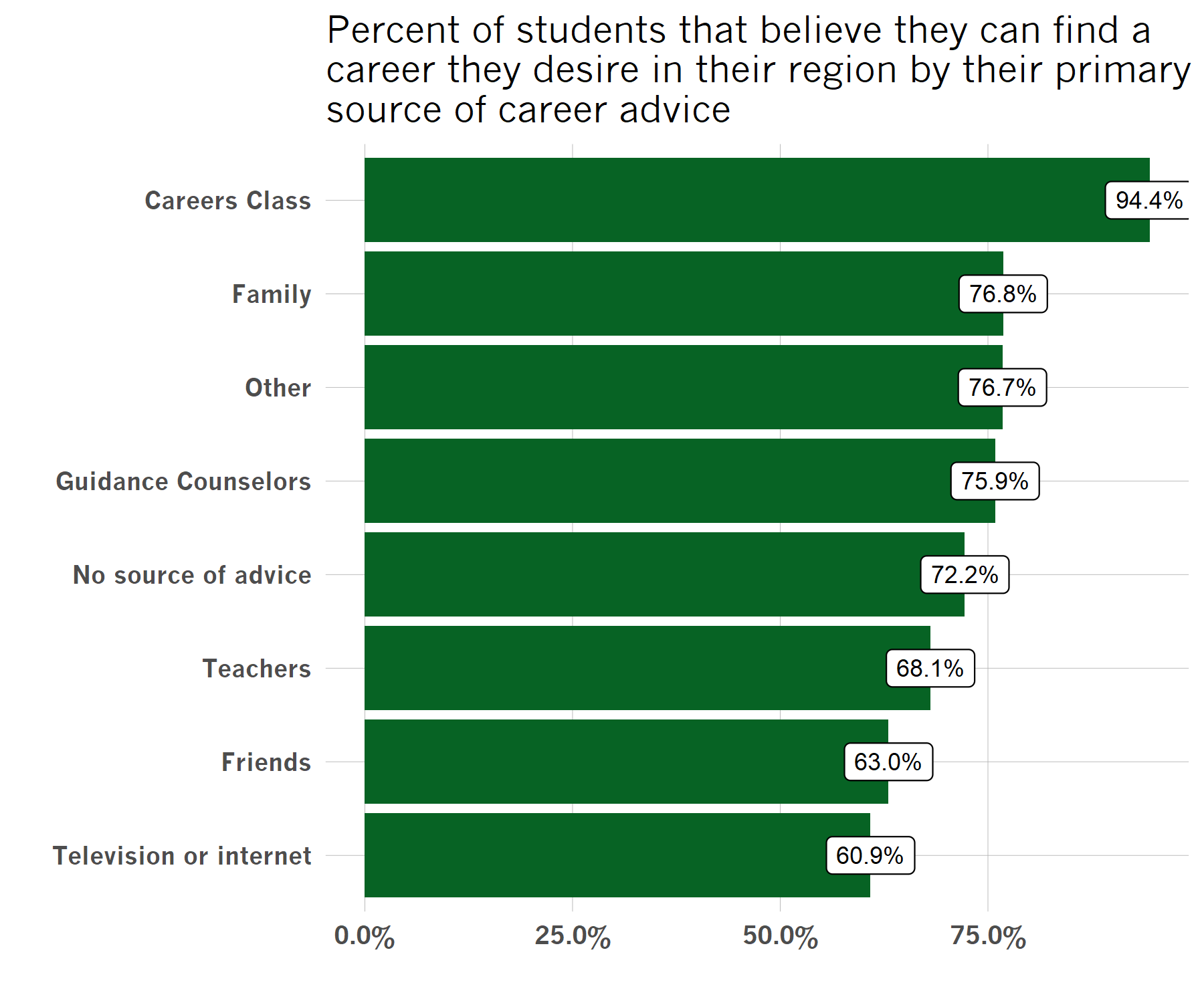

DEED’s survey of high school students is showing that the way in which these programs immerse students in careers and opportunities in the region may be having a significant impact on the current outmigration of young people from rural areas.

In the 2018 student survey, the 700 or so students participating were asked where their primary source of career advice came from. Only 18 students said that primary source was their career exploration class, but of those 18, 17 then responded that they believed they could find the career they wanted in their home region (Figure 3), demonstrating the kind of impression these career development programs can make.

Figure 3: 94% of students who said that their career exploration course was their primary source of advice believed they could find work in the career they want in the region in which they reside. Source: MN DEED Student Survey

So far, LYFT Pathways has been able to fund the development of 30 programs across southwest Minnesota and is projected to serve over 1,000 students, a tremendous change from two years ago. Other similar career and technical education programs exist, such as Bemidji Career Academies and Bridges Career Academies and Workplace Connection in north central Minnesota.

The longest-running technical and career education institution in the state is Wright Technical Center, located in Buffalo. CEO Mark Lee says the program’s ability to survive for so long is due to its funding structure. Instead of school districts paying per each student that attends, they use a blended model, where each of the eight school districts involved pays a share of the costs based on the percentage of juniors and seniors at their schools in addition to the number of their students who attend the center.

“School districts that used to pay only a per-pupil fee [found that] when no students attended, then that school didn’t pay anything,” he explained.

There are many other ways in which employers, organizations and government agencies are partnering to engage high school students, such as apprenticeship and pipeline programs aimed at providing real-life, on-the-job experiences for students. And like AGCO’s strategy to involve parents, these efforts are aimed at not only engaging students, but also providing parents, local leaders, and entire communities with information that helps to change the narrative on where opportunities for their children lie.

Barriers

Our interviews with program leaders revealed a few barriers the state could address to ensure these efforts to build an engaged local workforce continue. Many of the barriers revolved around cost. Career and technical education programs are expensive in terms of facilities, teachers, and transportation. Currently, school districts are expected to cover some of the costs for these programs while other organizations such as LYFT Pathways provides grant funding. There is concern, though, that if this supplemental funding didn’t exist, many of these programs wouldn’t survive financially.

Transportation: “LYFT Pathways currently provides funding, so the only cost to the school districts is the transportation, which can also be quite high. Without the LYFT dollars, I’m not sure the program works from a financial sustainability standpoint,” said Lakeview Public School superintendent Chris Fenske.

Tom Hoff, career and technical project coordinator for LYFT Pathways, agrees that one of the largest barriers and a unique issue for shared career and technical education programs in Greater Minnesota, is the distance between partnering schools. In the hybrid instructional model used by CTE partnerships, the students travel a couple days a week for center-based instruction, then participate in community or online experiences the other days.

“On days that they travel, the school has to either provide transportation (some do) or receive parent permission for students to transport themselves. At this time, there is no state funding to cover the additional transportation costs for center-based instruction,” Hoff said.

Instructors: Contributing to the cost issue is the shortage of teachers who focus on these technical skill areas. Currently, for these programs to qualify for Perkins V funding, a principal source of federal funding to states for career and technical education programs, the teacher must have a Minnesota Secondary Teaching license. However, the only place these programs can often find instructors with the necessary technical skills is at technical colleges, and faculty members there rarely meet the licensing requirement. As a result, the program cannot get state approval that would open up access to Perkins funding.

State graduation requirements can also get in the way of student participation in these programs. Currently, many of these programs don’t count toward state math or reading requirements needed for graduation. Supporters of these career and technical education programs fear that this “either-or” situation puts a limit on students’ options to explore careers.

Build Dakota Scholarship Program

But just as community leaders are starting see success in convincing students to stay in their home regions, another hurdle has cropped up.

Like Minnesota, South Dakota has been grappling with a workforce shortage, not only in their growing metropolitan regions, but in rural South Dakota as well. And similar to Minnesota, conversations about the issue focused on the lack of people entering the skilled-labor industries.

The result of South Dakota’s discussions is Build Dakota Scholarship, a program that provides students entering South Dakota tech schools an opportunity to graduate with no debt and a job in a high-demand field. The program receives major funding from the Denny Sanford Foundation and the state of South Dakota. Its stipulation is that the scholarship recipients commit to living and working in South Dakota, in their field of study, for three years following graduation.

According to Deni Amundson, program manager for Build Dakota Scholarship, the most surprising result of the program has been the engagement and support of the businesses and communities.

“When the program first started, the intention was to give 300 scholarships per year for the first five years, and then drop down to 50 per year” so the program could sustain itself off the initial endowment, Amundson said.

“However, we didn’t realize the success we would have in finding industry partners that would contribute to the funding, and we are very confident that we will be able to provide even more scholarships than initially expected.” Through the program, South Dakota employers and even communities will interview and hand-pick students they want to sponsor through the course of their higher education and employ afterward.

What has leaders in southwest Minnesota apprehensive is that this scholarship program is open to in-state and out-of-state students. Although only 10 to 25 of the 300 scholarships each year have gone to Minnesota students to attend schools and work in South Dakota, Bruce Bergeson, director of the Minnesota Valley Career and Technical Education Collaborative, says he is hearing more and more students indicate that they plan on going to South Dakota after graduating high school. That has him concerned.

“As we develop programs to expose more students to technical education and careers, we may end up losing those students to South Dakota for the free tuition,” Bergeson said in an email interview. “State leaders need to know that not only are we having to recruit (heavily) our students into technical career paths in hopes of plugging the employee shortage, but we are also fighting a battle with other states who seem to be better armed at getting our students into their schools and committed to working in their state.”

Recommendations

Schools, businesses and workforce development organizations are not sitting around when it comes to engaging high school students and working to reverse the negative narrative that says opportunity lies outside of their communities. Many programs and strategies being tried in rural areas are producing results, but there remains concern over their long-term sustainability. Following are some recommendations:

- The cost of transporting students to programs and work sites can be the biggest barrier for rural school districts. Supporting transportation costs for school districts that participate in—or want to participate in—career and technical education collaborations would be a valuable area to explore.

- Can these various programs (CTE, CEO, etc…) be tweaked so that they contribute to students’ graduation requirements? Right now, if students have to choose between exploring local, high-demand careers and taking courses that meet graduation requirements, they must choose the graduation requirements.

- Due to the teacher shortage, it is extremely challenging for career and technical education programs to find teachers that meet the state’s secondary teaching license requirements, which puts these programs at risk of losing out on Perkins funding. Can changes be made to allow school districts more flexibility in hiring instructors so that they can access Perkins funding?

- While Build Dakota may seem like another obstacle in the ongoing battle for workers, the program could be looked on as a model for a similar program here in Minnesota, where we already have an impressive infrastructure of higher education institutions and K-12 schools. We also already enjoy a high rate of cooperation between businesses and workforce development programs, and we have many philanthropic organizations with a history of investing funds in promising long-term projects. Is Minnesota ready for a similar model?

[crpd_nested_box]

All Articles in this Series:

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 1

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 2

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 3

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 4

[/crpd_nested_box]