Engaging populations with high barriers to employment; Greater Minnesota feels left out

April 2019

By Kelly Asche, Research Associate.

For a printable version, click here.

All Articles in this Series:

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 1 – the data

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 2 – resident recruitment

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 4 – changing the narrative for high school students

Check out our explainer video, “Why do we have a rural workforce shortage” for a quick overview of this research.

As employers hit the end of what’s known as the “slack in the labor force”—that percentage of the population ages 18–64 not participating in the workforce—they are running up against something new: engaging with and recruiting workers from groups of people living in particular circumstances that make it difficult for them to hold jobs. It is not that these potential workers are unwilling to work, but that they are struggling with high barriers to employment that must be addressed if they are to enter the workforce and be able to stay there.

Addressing these barriers often means connecting the potential worker with services to help them with things like housing and child care. The difficulty employers, workforce trainers, workforce officials, and policymakers are coming up against, however, is that the idea of wrapping these services in with workforce training is a new concept, one that comes with extra costs, and attempts to come up with a means of paying for this new system don’t always work out as intended.

Through interviews with nearly 30 businesses and workforce development organizations, we reviewed these barriers to employment and how they affect someone’s employability from both the worker’s and the employer’s standpoint. We also took a look at a potential problem with the way programs meant to help people overcome these barriers are funded in Greater Minnesota.

Workforce training: The new reality

The familiar workforce training model is one based on a problem of too many workers for too few jobs. The unemployed workers coming to workforce development organizations (WDOs) for help have in the past generally been people who lost a job and needed help, usually in the form of retraining, to get connected with a new job. WDOs form the network of entities, both public and private, around the state that provide services and training laid-off workers need to get re-employed.

Since the Great Recession, however, circumstances have taken an unprecedented turn: Due to demographic forces, we now live in a model of too many jobs for too few workers. Instead of workers coming in looking for help finding a job, businesses are now coming to workforce development organizations looking for help in attracting workers.

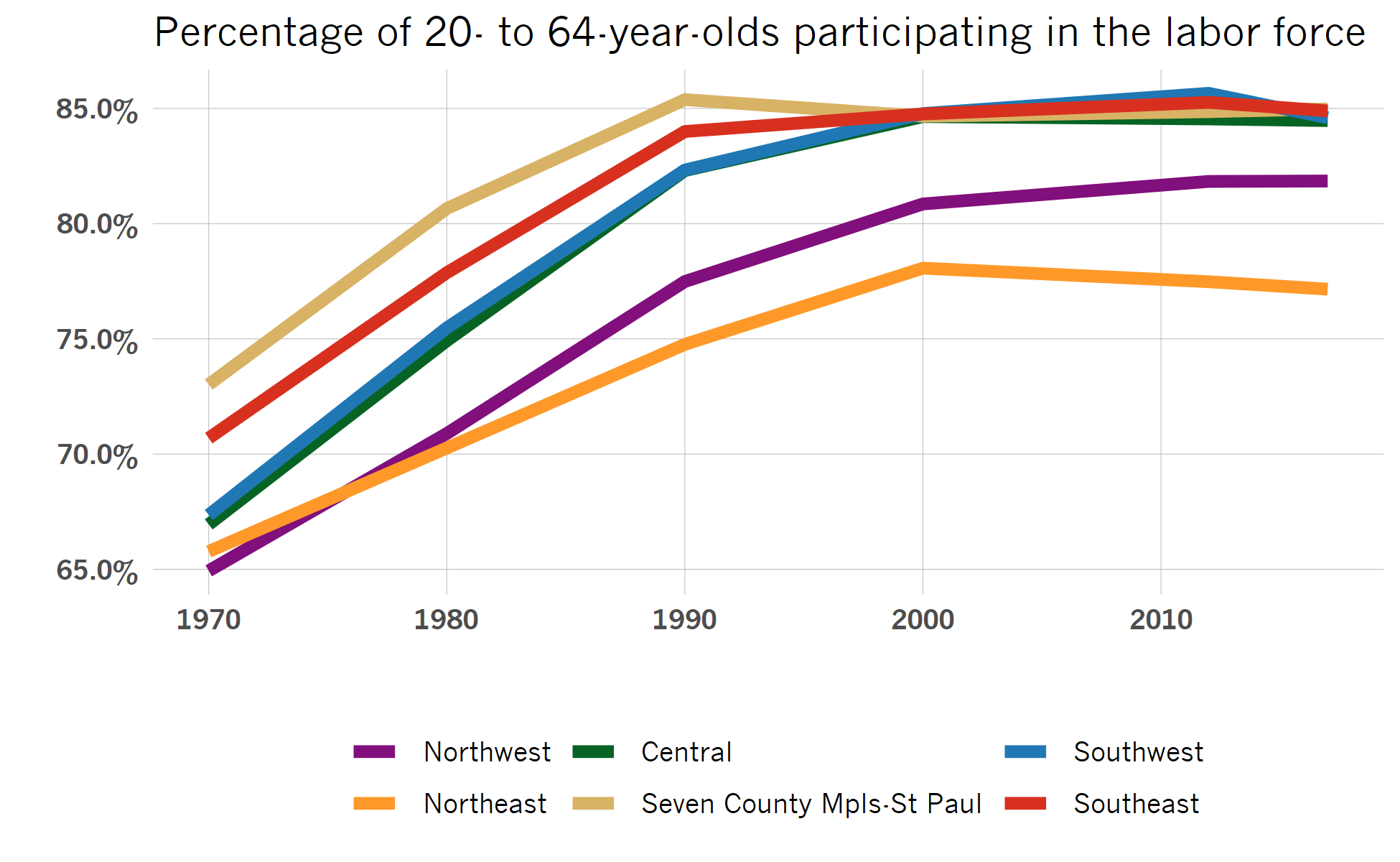

Between 1970 and 2000, the percentage of the workforce-age population (defined here as 20- to 64-year-olds) participating in the labor force increased significantly. As Figure 1 shows, some regions of the state maintain a very high participation rate, while some are lower, but all the curves have flattened out, indicating that some type of resistance is keeping the remaining percentage out of the workforce.

That resistance, employers are finding, is in the form of high barriers to employment, life circumstances that make it difficult for someone to get and hold a job. People can fall into one or a combination of categories:

- Individuals with disabilities

- Individuals with criminal backgrounds

- Immigrants and refugees, and

- Individuals in dire financial circumstances.

To be able to succeed, people with high barriers to employment need an additional level of support not usually necessary for an average worker who has been laid off.

What are high barriers to employment?

Employers have taken steps to smooth the path to employment for potential workers. Since the recession, employers have been progressively lowering the education and experience requirements for their open jobs in an effort to attract workers. Employers are also providing applications in multiple languages and in different formats, conducting “stay interviews” (think exit interviews but asking employees why they stay), and really studying what will help keep the worker turnover down.

Such strategies only go so far, however. As the pool of applicants shrinks, employers are increasingly looking toward segments of the population they haven’t engaged with much yet—populations with high barriers to employment. For workers, these barriers combine to interfere with day-to-day tasks we take for granted:

- Transportation: Access to reliable transportation can be a consistent problem for individuals, not only for getting to work, but also to trainings and other programs intended to help them find employment.

- Child care: Access to child care is challenging for most Minnesota parents, but the shortage of providers makes it even more complicated for certain groups, particularly in Greater Minnesota, including immigrants and refugees looking for culturally appropriate child care or a single parent in poverty, for whom finding affordable child care can be very difficult.

- Housing: Finding consistent, reliable, affordable housing can be a major barrier to anyone looking for work all over Minnesota. For people who need special accommodations for a disability, someone with a criminal record, someone who doesn’t speak English, or someone with a very low income, finding housing can be especially problematic.

- Health care: Lack of insurance or even a nearby clinic or hospital can mean prolonged absences due to illness, coming to work sick, absences for staying home with sick children, and overall poor health.

- Required absences: Persons may come to a job with obligations they have little to no control over, such as attending court-ordered counseling or reporting to a parole officer on a regular basis.

- Substance abuse: Although opioid addiction is a critical issue, just as concerning is the increasing use of and addiction to meth and other drugs[1] around the state. A common complaint heard from employers is the inability to find a worker who can pass a drug test.

All of these issues work together to create a complicated web of recurring situations preventing people from getting and sticking with a job. For example, workforce development organizations in northeastern Minnesota developed a 240-hour fast track training program for welding to help fill positions for area businesses. The twenty slots filled up immediately, but in the end half of those individuals didn’t finish the program due to ongoing struggles with substance abuse, finding daycare, and/or reliable transportation.

“Several students had their cars break down,” says Heath Boe, a rural workforce coordinator for the Northeast Minnesota Office of Job Training. “They didn’t have money and so [they] had to wait for a friend to fix it for them. Without public transportation, there was just no way for them to get to the trainings.”

Managers at JBS Pork in Worthington took the initiative to overcome the language barrier causing difficulties for many workers at their facility. Len Bakken, Director of Human Resources at JBS, estimates that over fifty languages are spoken in JBS work places. To communicate necessary safety and training information, they installed kiosks showing informational videos in every language spoken there.

“We’ve invested a lot of money, time, and other resources, not only for job training and communicating safety information, but also into integrating these populations into the community,” Bakken said.

Barriers also come from the business side, which fall under a couple of themes:

- Fear of the unknown, and

- Perceptions held by employers about people dealing with high barriers.

These themes are familiar to Tammy Biery, the leader and facilitator for the Immigrant Employment Connection Group in St. Cloud. When the group started, Biery expected most of the work would involve focusing on educating and connecting their East African refugee clients to employment opportunities.

She realized, however, that some of the larger barriers to employment for this population came from the employers in the form of false perceptions and lack of information.

“We quickly learned that we needed to educate employers to help them understand the culture, dispel some myths, and get them comfortable with the idea [of having Somali employees],” Biery said.

In 2015, Biery and her organization helped one local Somali elder put on a job fair for his community, only to find out afterward that employers ended up not hiring anyone even though they needed workers. It turned out that employers were concerned by the unknowns of working with people from a culture they considered very different from their own and by stories floating around the community that turned out to be inaccurate concerning things like prayer time, washing traditions, and handling of certain foods, Biery said.

Perceptions are a problem for individuals with criminal histories as well. Mark Schultz, labor analyst for the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development (DEED), created a three-hour training to help employers and others understand the issues that go with hiring people with a criminal background. The first hour of the presentation is dedicated to busting myths.

“Many businesses may have the perception that ‘criminal’ equals ‘bad employee,’ and that is far from the truth,” says Shultz.

Employers do need to understand that a person with a criminal background does need some flexibility in his or her schedule to be able to coordinate any legal responsibilities that go along with release, such as reporting to a parole officer.

Kate Erickson, housing coordinator for the Minnesota Department of Corrections, says she’s getting more calls from employers than ever before about hiring people coming out of prison, but she has to tell them that hiring is just one small piece of the employment puzzle.

“Many individuals who have recently been released from incarceration and have been out of the workforce for a long period of time have a lot of other pieces in their lives that need to line up,” Erickson says. “Housing stability, attending mandatory meetings, counseling and battling addiction, and coordinating with social workers are all different pieces that require flexibility among employers.”

For people in extreme poverty, life situations that would cause minor problems for a typical household can create serious consequences.

As Traci Tapani, co-president of Wyoming Machine Company, explains, “When bringing on new employees that experience barriers to employment, many times these people are in dire straits financially and are one unfortunate life situation away from being broke.”

An article from the Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation provided results from a survey of employers to determine the primary reasons why an employer would be reluctant to hire someone with disabilities (Table 1). Even though the research focused specifically on people with disabilities, replacing the word “disabilities” with phrases like “criminal history,” “language barrier,” and “extreme poverty” would provide similar results.

|

|

Reason |

|

1 |

They (employers) are worried about the cost of providing reasonable accommodations so that workers with disabilities can do their jobs. |

|

2 |

They don’t know how to handle the needs of a worker with a disability on the job. |

|

3 |

They are afraid they won’t be able to discipline or fire a worker with a disability for poor performance because of potential lawsuits. |

|

4 |

They can’t ask about a job applicant’s disability, making it hard to assess whether the person can do the job. |

|

5 |

They are concerned about the extra time that supervisors or co-workers may need to spend to assist workers with disabilities. |

|

6 |

They are worried about other costs, such as increased health insurance or worker’s compensation premiums. |

|

7 |

They are afraid workers with disabilities won’t work up to the same standards as other employees. |

|

8 |

They rarely see people with disabilities applying for jobs. |

|

9 |

They believe that people with disabilities can’t do the basic functions of the jobs they are applying for. |

Providing a network of services

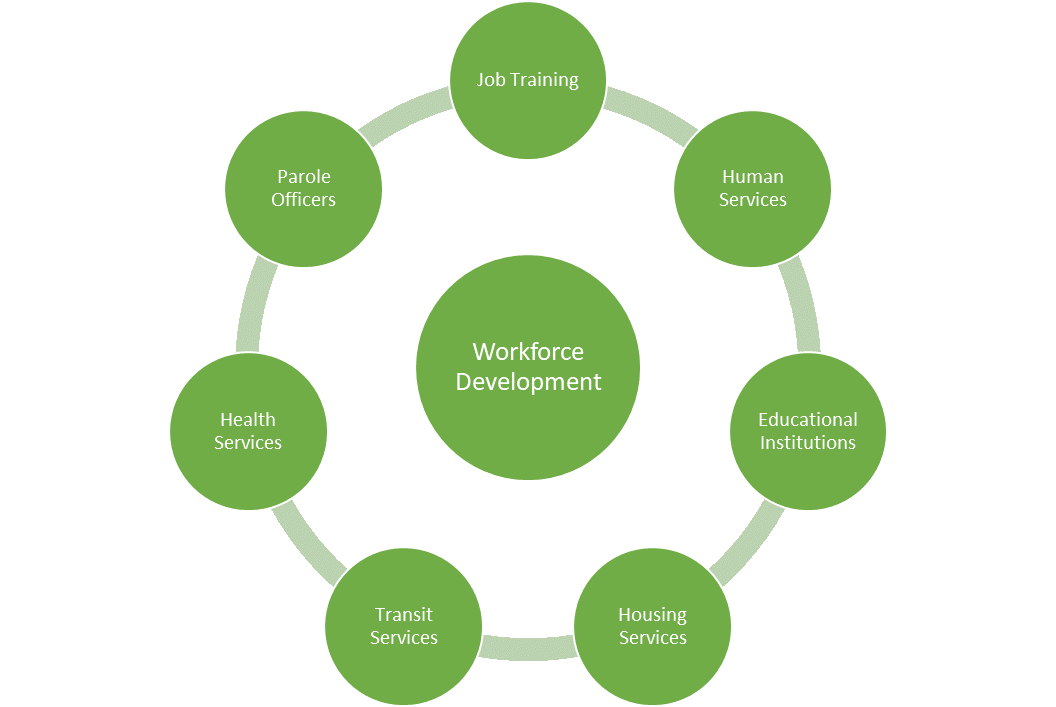

For all of these reasons, serving individuals with high barriers to employment is becoming increasingly about providing a holistic set of services that until now haven’t typically been included in workforce development programs.

Beyond training people in specific job skills, WDOs are now partnering with more state and local agencies and community organizations to build networks of support services for individuals with high barriers to employment (Figure 2).

But while the need for services is growing in both the Twin Cities and Greater Minnesota, delivering these services in rural areas tends to be more difficult and more expensive compared to delivering them in the Twin Cities, and workforce development professionals feel there is a lack of understanding among state agencies in St. Paul about the differences.

Due to low population density, many workforce development organizations serve very large regions. For example, the Workforce Development Boards in Greater Minnesota each serve seven or more counties, regions that can take three to four hours to drive across. Organizations try to provide as many in-person access points as possible across their regions but doing so substantially increases the cost of providing services, and while organizations are looking at providing more resources online, access to broadband can be a challenge for the populations they are serving, too.

In southwestern Minnesota, three workforce centers serve fourteen counties, says Carrie Bendix, executive director of the Southwest Private Industry Council.

“Clients must travel further to access programming, and especially with the limited access to public transportation out here, access to any in-person services isn’t anywhere near the same [cost] as it is in the metro,” Bendix says.

They have to be very strategic to be cost-effective about how and where services are provided in rural areas since workforce development organizations serve populations that tend to be dispersed across a region and not concentrated in one place, as in densely populated urban areas, says Bendix.

Paying for it all

According to the workforce development professionals we interviewed in Greater Minnesota, despite the higher costs to provide services and support programs in rural areas, they perceive the system set up to distribute state funds to worker programs works to Greater Minnesota’s disadvantage.

Funding for the many workforce programs in Minnesota comes from multiple streams, which can make it a challenge to calculate the cost per participant for most of the programs. The programs that serve people with high barriers to employment, however, are funded mainly through three sources: the federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), which goes directly to the Workforce Development Boards, grants from the Minnesota Job Skills Partnership Program (MJSP), and a funding stream in DEED’s budget known as the State Adult workforce fund.

WIOA was originally created by the federal government to fund workforce development programs at the state level, including the dislocated worker program. Minnesota is unique in that it provides additional, supplemental funding for programming. It does so by charging a fee to all businesses in the state, which then goes into the Workforce Development Fund. The intention of the two funds is to support programs that help workers find jobs during economic hard times.

Because dislocated worker programs aren’t needed that much during times of very low unemployment, such as now, the money is diverted into other programs within workforce development (labeled as State Adult workforce fund). This includes paying for programs providing help to workers with high barriers to employment.

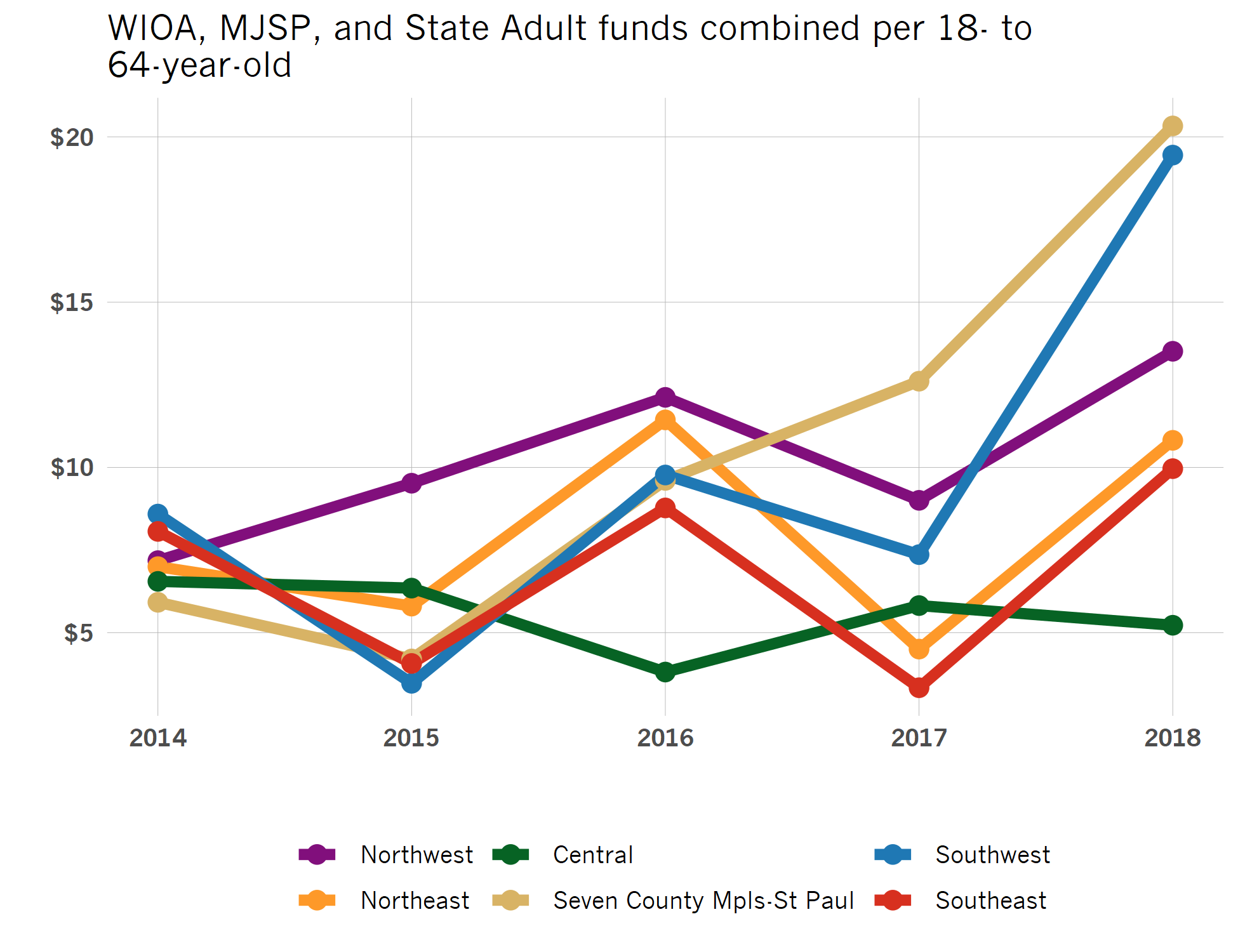

Figure 3 shows that since 2014 the combined amount of WIOA, MJSP and State Adult workforce funding each region has received per workforce-age resident has diverged quite a bit. In 2018, the Twin Cities metro area received $20.33 per 18- to 64-year-old compared to $19.45 in the southwest and $5.22 in central Minnesota.

Data: MN DEED Employment and Training Resources Report Card | U.S. Census Bureau, Population Estimates

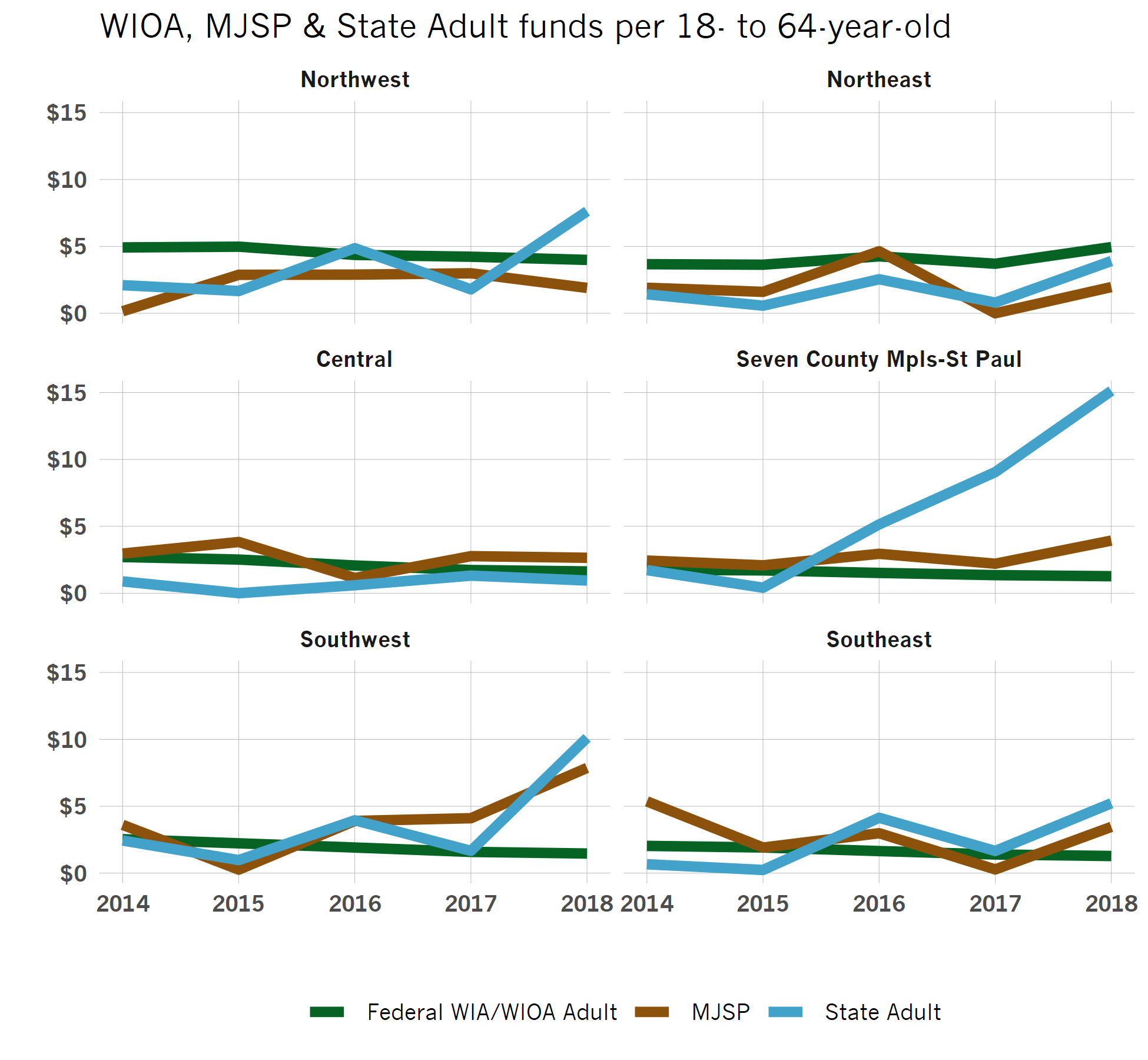

Charting each funding source separately (Figure 4) shows the federal WIOA funding staying fairly stable or even trending downward in each region. Funding for MJSP is dependent on whether a region is awarded a grant, such as Southwest in 2018. The real change, however, has happened in the last few years to the State Adult workforce funding. Between 2016 and 2018, State Adult workforce program funds have gone from averaging $5.14 per 18- to 64-year-old to $15.13 in the Twin Cities region. In Greater Minnesota, the state program funding averages in 2018 ranged from $10.12 in the southwest to $0.95 in central Minnesota.

Data: MN DEED Employment and Training Resources Report Card | U.S. Census Bureau Population Estimates

State Adult funds are disbursed to regional programs through two methods: direct appropriations and competitive grants.

Direct appropriations: In 2017 and 2018, direct appropriations in the State Adult fund awarded over $26.5 million to twelve organizations serving the Twin Cities metro, $1.8 million to three groups serving both the Twin Cities and Greater Minnesota, and $1.6 million to four organizations based only in Greater Minnesota (Table 2). See appendix A for the list of organizations.

|

Region |

Number of organizations/programs funded |

Funding Amount |

|

Serving Twin Cities only |

12 |

$26,475,000 |

|

Serving Twin Cities and Greater MN |

3 |

$1,843,000 |

|

Serving Greater Minnesota only |

4 |

$1,585,165 |

Competitive grant funding: Workforce development organizations also feel left out as more funds are disbursed through a competitive grant system, typically via DEED. The workforce development professionals in Greater Minnesota interviewed for this study don’t object to a competitive grant system since it can spur innovation and new ideas, but they are concerned that the unique logistical issues many workforce development organizations in Greater Minnesota face when providing services were not taken into consideration when the priorities and eligibility point system for the application process were developed.

One of the first issues many workforce developers in Greater Minnesota brought up is that their programs can’t be compared to Twin Cities organizations on the basis of cost per person served. Dense population—more clients within a smaller service area—means Twin Cities-based organizations will almost always be more competitive in terms of return on investment per client. Grant processes that give priority to proposals with higher ROI will immediately put most workforce development organizations in Greater Minnesota at a disadvantage.

In addition, some of the grants have required or incentivized applicants to develop programs using a “cohort model”—grouping together clients who enter and work through the program at the same time, similar to a class of students in a school.

This model essentially disqualifies smaller organizations in Greater Minnesota: with the smaller numbers of enrollees spread across a larger region at any one time, it’s simply impractical and therefore financially unfeasible to depend on this kind of model, says Kiki Anderson, executive director of the Northwest Private Industry Council.

Lastly, there was extra focus on diversity in the last round of grants, particularly the diversity of an organization’s board of directors. While all the workforce development professionals interviewed believe diversification to be vitally important, many organizations didn’t even apply for these particular grants, assuming they would be disqualified because of a lack of diversity on their boards. Putting together a diversified board in Greater Minnesota outside of the larger population centers is difficult enough, but the requirement causes a particular problem for Workforce Development Boards, where nearly all their board members are prescribed in federal legislation. Considering Greater Minnesota’s small minority population outside of urban areas like Rochester or St. Cloud, finding people of color to fill a specific role on a board can be very challenging.

Looking ahead

By and large, workforce development organizations in Greater Minnesota know they have the tools and programs to help people with high barriers to employment. They are forging new partnerships and collaborating more than ever with other entities to help workers with high barriers to employment get the help they need to make it in the workforce. But with recent changes in how program funds are distributed, there is a pervading feeling that the cards are stacked against rural regions.

As Minnesota employers struggle to find workers and the state considers the ramifications of the workforce shortage on the overall economy, two suggestions would be for state policymakers and agencies to take a closer look at how many people are served by these various programs and the cost to serve them, and then to review how funds for workforce development activities are distributed to ensure they are being spread across the state in a manner that is proportionate to regional needs.

[1] https://www.ruralmn.org/its-an-addiction-crisis/

[crpd_nested_box]

All Articles in this Series:

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 1

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 2

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 3

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 4

[/crpd_nested_box]