From chasing smokestacks to chasing people – the new mission of rural communities

March 2019

By Kelly Asche, Research Associate.

For a printable version, click here.

All Articles in this Series:

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 1 – the data

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 3 – engaging populations with high barriers to employment

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 4 – changing the narrative for high school students

Check out our explainer video, “Why do we have a rural workforce shortage” for a quick overview of this research.

For years, the focus for economic development policy has been about “jobs, jobs, jobs!” Now, businesses and workforce development organizations are saying, “People, people, people!” Communities in Greater Minnesota are now recognizing that strategies focused solely on recruiting and retaining jobs have to change.

As baby boomers retire and population projections show a decline in the workforce over the next 20 years, rural regions in Minnesota are looking increasingly for ways to draw people into their regions. But there are significant challenges in implementing this work in Greater Minnesota.

Rural leaders are finding that people recruitment initiatives are complex and require a central organization—and the level of resources—that can muster and direct a large number of players, many of whom haven’t typically collaborated before and come from across a large geography.

And on top of all this, the leaders of these initiatives have to fight a stubbornly ingrained negative narrative about rural areas held not just by those on the outside looking in but by rural residents themselves.

Leavers and returners

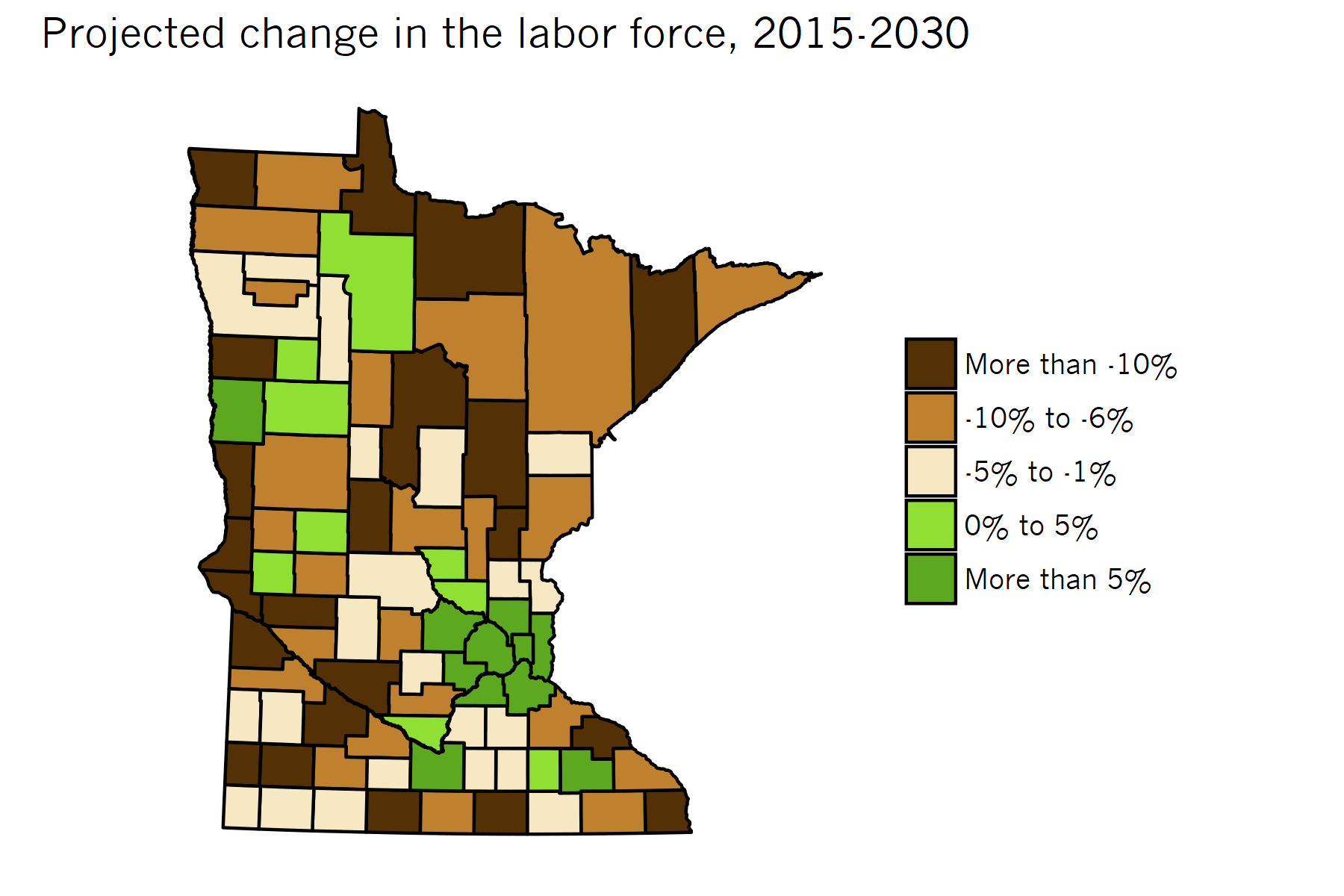

In the first part of our series on the workforce shortage[1], we reviewed what’s going on with job vacancies around the state. The data is clear: the workforce shortage has arrived in Greater Minnesota, and it’s projected to get worse. The Minnesota State Demographic Center is projecting that if trends don’t change, the number of people in the labor force will decrease significantly in counties across Greater Minnesota. Of the state’s 87 counties, 67 of them are projected to have fewer people in the labor force by 2030 than today, and all of those counties are located outside of the Twin Cities seven-county metro (Figure 1).

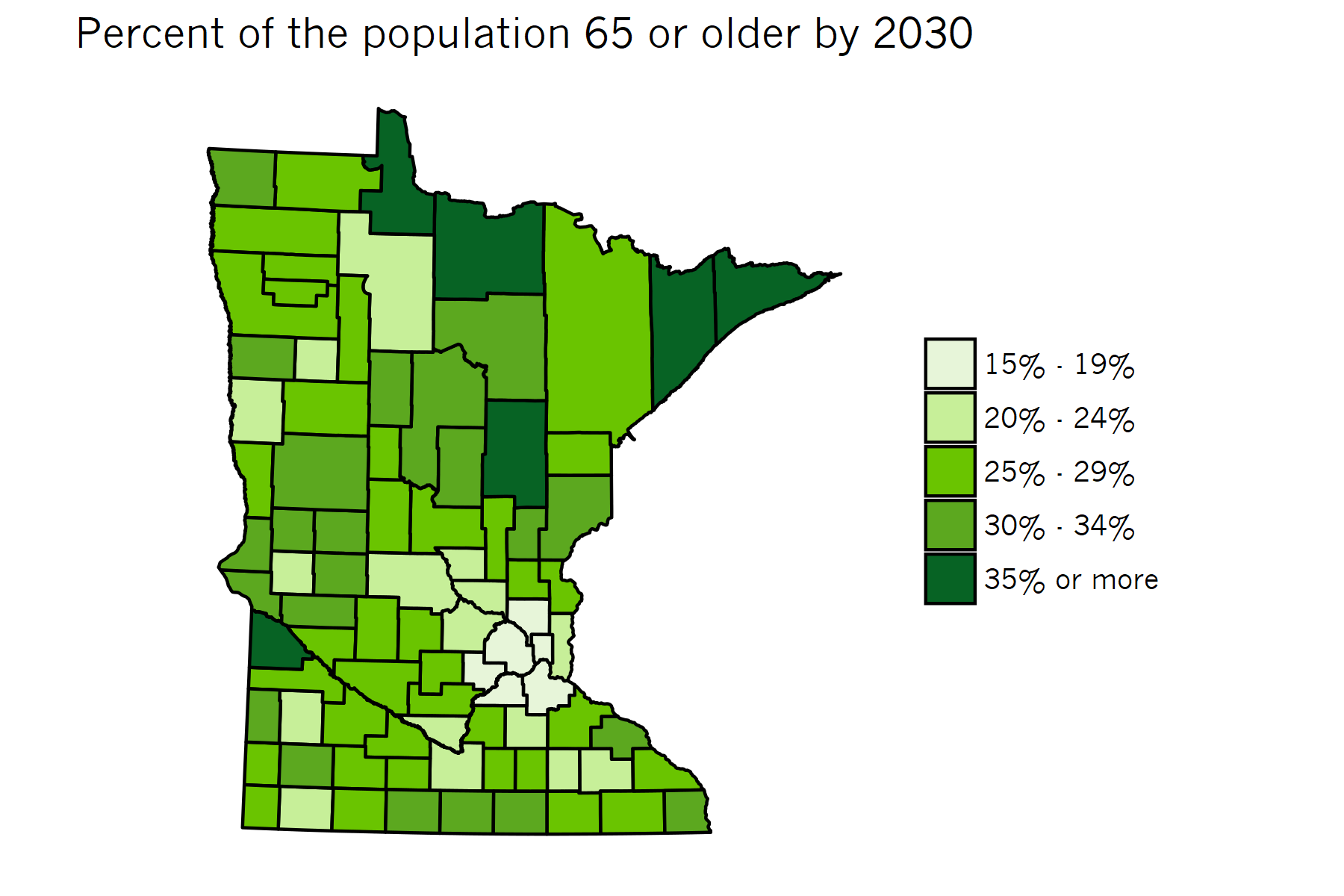

This projection is based on a double whammy of demographic change and migration trends:

- Greater Minnesota’s population tends to be older, meaning a larger-than-average share of the population is exiting the labor force over the next decade (Figure 2); and

- 20- to 29-year-olds, part of the population meant to replace retiring baby boomers, tend to leave Greater Minnesota.

But while these patterns and projections look dire for Greater Minnesota, a movement is forming among community and economic development organizations who believe they can turn this trend around.

The basis for their optimism is research out of the University of Minnesota Extension Center for Community Vitality known as “The Brain Gain.”[2] This trend counters the “Brain Drain” trend that has come to define rural areas by challenging the long-held belief that rural communities must keep their young people in place. The research shows that although 20- to 29-year-olds leave many rural regions, there is a corresponding boomerang of people in their 30s and 40s who migrate into rural areas.

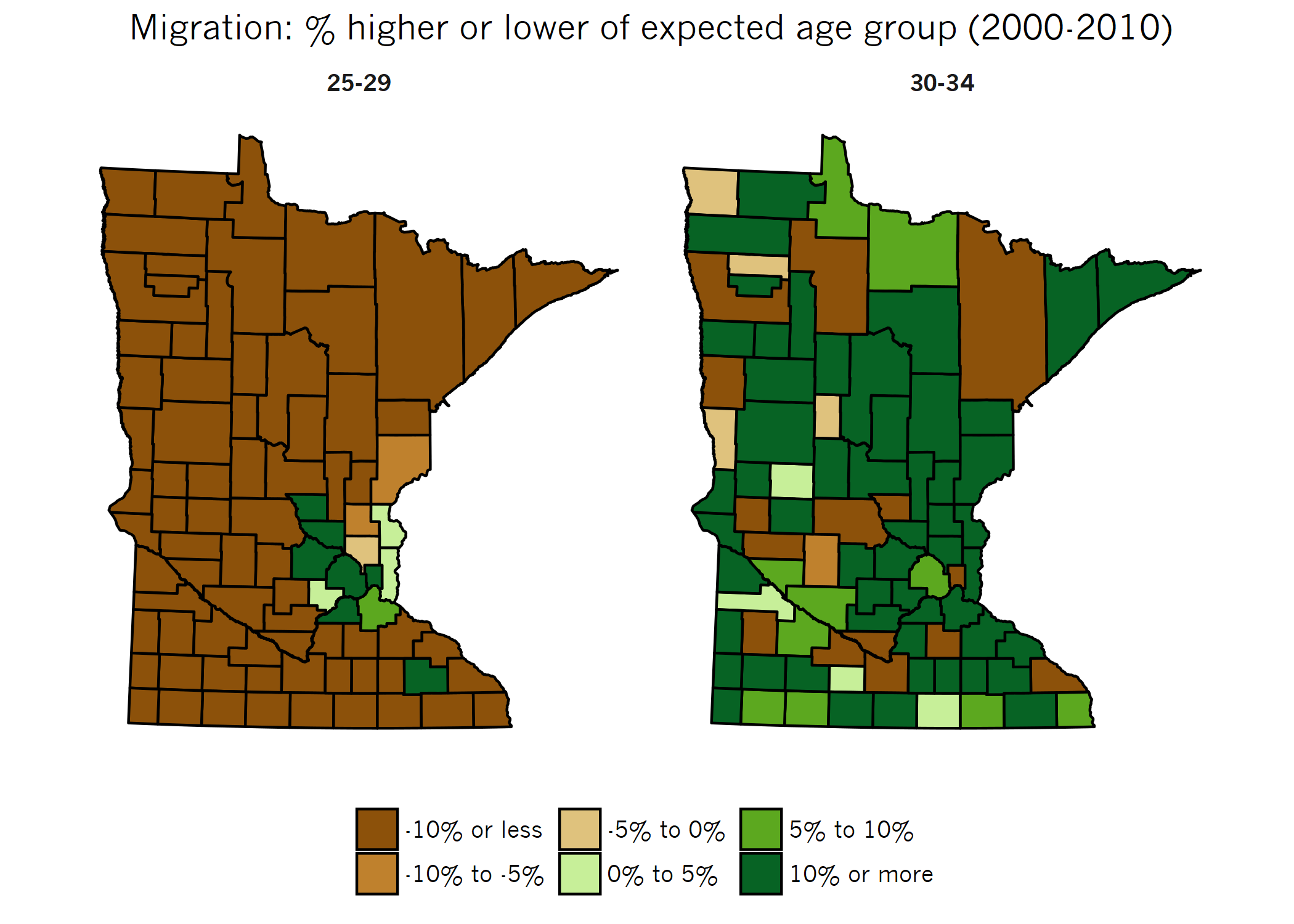

Such is the case for Minnesota. Any location in the state can expect that, assuming all conditions stay the same, the number of 25- to 29-year-olds counted in the 2010 census would be equal to the number of 15- to 19-year-olds counted in the 2000 census—the same people, just ten years older. Migration happens, however, and we find that at the end of that ten-year period there may be more or fewer people than would be expected for that age group—hence an in-migration or out-migration.

Figure 3 shows that between 2000 and 2010, all but a handful of rural counties experienced an out-migration of people in the 25- to 29-year-old age group in 2010. Looking at the next age group up, however, shows an in-migration of people in the 30- to 34-year-old age group into most rural counties. This in-migration doesn’t always outnumber the out-migration of young people, but the effect is noticeable.

Brain Gain author Ben Winchester states in his original research: “This trend is happening despite any region actively recruiting them. Imagine if we actually tried.”

Why would people move here?

The research also revealed that often as not, families were moving to rural areas not for a specific job opportunity but for the lifestyle. In studying this newcomer migration to rural areas, researchers asked newcomers in southwestern Minnesota (people who had moved into the region within the last five years) why they chose to relocate to a rural place. The top three responses were:

- Affordable housing.

- Small class sizes.

- Quality of life, a catch-all term for related responses, such as ‘slower pace of life.’

Surprisingly, “for a job” was not all that common. Many of the newcomers wanted a major lifestyle-change rather than a career move. It’s not that jobs weren’t important, but they weren’t necessarily the main or only driver influencing a household’s decision to move.

“We had one individual with a master’s degree in geophysics who moved here but also happened to have an interest and skills in finance. That’s the field he ended up working in to move here,” said Rick Schara, coordinator for the Live Wide Open campaign at West Central Initiative in Fergus Falls.

The organizers of people recruitment initiatives are hoping that there are more households that are willing to be flexible in careers to get the lifestyle they want.

On the other side of the coin, there are those who do move specifically for a job, and there are initiatives that have been developed to help welcome these newcomers to rural Minnesota as well: immigrants and refugees. Project FINE is an organization in Winona that has been assisting businesses in reaching out to these populations, which currently live mostly in metropolitan areas. These particular groups do move, but their moves are based almost exclusively on job availability. As Fatima Said, executive director of Project FINE, says, “With refugee and immigrant populations, everything starts with a job. All of them want to work and make a living.” The struggle for many regions in rural Minnesota is connecting to these largely urban populations.

Promoting and engaging

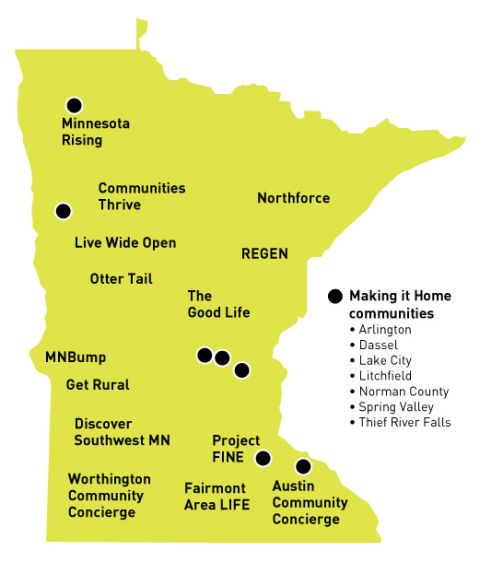

It’s these two ideas that communities in Greater Minnesota are latching onto and developing their initiatives around: to promote a region’s life-style and to connect with urban-dwelling households looking for a job but who may also be interested in living in a less densely populated area (Figure 4).

The structure and strategies of people recruitment initiatives vary: some are more regional, covering larger geographic areas and developing sophisticated promotional materials to be used by businesses and organizations. Others are more local and focus on person-to-person interactions, such as taking newcomers out to lunch, developing “welcome” committees, and using social media to show off everyday life in their community.

Funding sources for these initiatives is just as diverse. Businesses, non-profits and philanthropy organizations all contribute in various ways. The structure of the organization these initiatives are housed in often determines the type of funding sources available. Some regional recruitment initiatives are housed within regional development commissions or Initiative Foundations that function to not only organize the initiatives as a whole but also provide funding opportunities for smaller communities within their region to implement people recruitment strategies. Other more local initiatives, such as Project FINE, utilize a network of area businesses, philanthropic organizations, and other non-profits to fund their efforts.

These initiatives can be extremely complex. They require robust communication among many stakeholders across different levels of government, non-profits, and businesses that have never implemented or even been a part of such an effort before. Even convincing the stakeholders of what is possible is a hurdle.

To understand the complexity of this work and the amount of effort required, it’s important to understand all the points of engagement needed to turn someone into a resident. The first is often when someone visits the community. There are many points at which a visitor engages with a community or region.

Although this list is simple enough, the complexity comes in when determining how each player in these interactions can “sell” the lifestyle of the region to the visitor.

For example, tourism efforts have a long history in Greater Minnesota, and as such, more regions are beginning to look at this asset as a way to recruit people to not just visit but stay. Research conducted by Longwoods International with Explore MN in 2017 found that “tourism functions as the front door for economic development” since people who visited Minnesota were much more likely to view Minnesota as a good place to live, start a career and/or a business.[3] This idea applies to visitors from both metropolitan areas and rural areas.

The Convention and Visitors Bureau for the city of New Ulm has taken this advice to heart. In the last few years, they have incorporated relocation information into their tourist materials, including a community calendar showing dates for concerts, organization meetings, and other community events not necessarily related to tourism. Social media is also used as a marketing strategy.

However, tourism doesn’t encompass everything. “Visitor” can also include someone coming to town for anything from visiting family to attending a job interview to stopping to simply fill their gas tank. Thinking in these terms means an entire community and/or region must be prepared to recruit. It also means the smallest interactions become important. Are businesses prepared to sell not just their job position to a potential candidate but also their community? Do community members have a narrative that talks about their positive experiences there? Are employees at retail stores, gas stations and grocery stores trained to interact with all visitors in a way that promotes the community?

Being strategic about the myriad interactions a visitor has in a community is vital to the success of these initiatives.

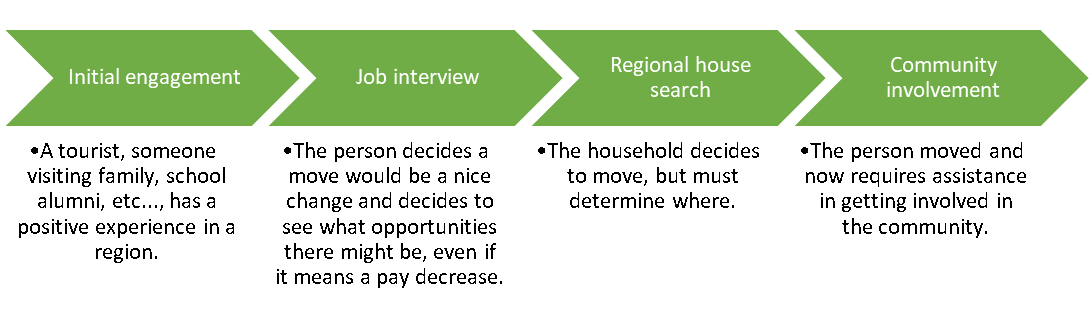

These initial contacts are just the beginning, however. Engagements must continue along a continuum—from an initial visit to an initial job interview to the actual decision of moving (Figure 6).

This level of engagement requires someone or some organization to provide information on each aspect of the decision to move—information such as houses in the region, recreational opportunities, and active local organizations that increase quality of life (Figure 7). This information, if available at all, is generally spread across numerous entities—workforce development boards, businesses, chambers of commerce, economic development authorities, tourism boards, colleges, churches, community-based organizations, and schools, just to name a few.

Figure 7: The “ingredients” for a people recruitment strategy called “Get Rural MN” developed by the Upper Minnesota Valley Regional Development Commission shows all the ways in which these initiatives attempt to promote a region. Source: https://umvrdc.org/program/get-rural-mn/

Still a new concept

But although some of these initiatives have been around since the early 2000s, the idea of developing entire initiatives around people recruitment is new to most of Greater Minnesota. Many of the existing programs started in the last five years.

“We’ve been meeting with ten of our largest employers who have a number of job vacancies. When we ask them what type of marketing they are giving to job candidates about the region, the response is usually ‘nothing’,” says Melissa Streich, communications coordinator for the Upper Minnesota Valley Regional Development Commission. “That is where there is an opportunity for us to connect them with our recruitment efforts and marketing materials.”

Initiatives in rural areas face some unique challenges. The Twin Cities is also engaging in people recruitment initiatives, Greater MSP being an example. In the Twin Cities, a robust network of for-profit, non-profit, government and major media businesses can promote jobs, events, housing, and other opportunities not only to the local market, but statewide, to the entire Midwest, and even the nation. If someone is contemplating a move to the Twin Cities, information about jobs, events, night life, childcare, housing, and culture is significantly easier to find online than it would be to find the same information for rural parts of the state. The key for people recruitment strategies is identifying all of these resources and networking them together.

In rural areas, however, only a few pieces, if any, of these types of networks already exist, and their reach rarely extends beyond their local regions, much less into metropolitan areas. Information, both in print and online, promoting a region’s nightlife or available apartments or organizations to join or outdoor activities is rare and typically hyper-local, focusing on a single community. As a result, people working on recruitment initiatives in Greater Minnesota must spend considerably more time building these resources up and out.

Matching jobs with job-seekers, for example, is a challenge. Families considering moving to Greater Minnesota will need jobs even if the job is not the primary reason for the move. But for those considering moving anywhere within a whole region, such as southern Minnesota or northern Minnesota or the central lakes region, where do they begin to search?

More importantly, how do employers get the word out to potential newcomers about available jobs? Most businesses in Greater Minnesota rely only on their local newspapers and other platforms that have limited market penetration outside the local area. To get a sense of how many platforms someone would need to search to find all the jobs available in a specific region, the Upper Minnesota Valley Regional Development Commission (UMVRDC), who developed the Get Rural initiative, conducted an experiment. For one week, they searched as many job posting platforms as they could find for jobs in the Dawson, MN, region. In total, they searched more than ten platforms (all the newspapers in the region counted as one platform) and found 110 total jobs. However, only 30 of those jobs appeared on more than one platform. In other words, a job seeker would have had to search all of the platforms, including all the newspapers, to be sure they were seeing all the available jobs in their field in that area.

There are job aggregating companies that pull job positions from multiple platforms into a single, searchable page, but these sites don’t play well with local recruitment initiatives, says Dawn Hegland, executive director of UMVRDC.

“The job aggregator sites available are typically too expensive for regional organizations to contract with and can have barriers in how the information can be publicized,” says Hegland. The sites tend to have a lot of errors or missing information in Greater Minnesota, she said.

In comparison, Greater MSP, the people recruitment initiative in the Twin Cities metro, contracts with a single job aggregating company that they believe is capturing between 80% and 90% of the jobs available in the area.

A new mindset

Another, perhaps even larger hurdle is that these initiatives require a transformation in how various businesses, civic organizations and regional leadership interact. Communities must consider the whole scope of a person’s decision to move, stay, and leave, requiring all potential organizations and businesses interacting with these folks to have a common goal of promoting their area.

To make themselves more accessible, communities within a region, with their different business mixes and civic leadership styles and capacities, need to collaborate at a regional level if they are going to develop strategies that promote the region to potential residents at multiple points in their decision-making process, says Neil Linscheid, Community Economics Educator with the University of Minnesota Extension.

Ideally, one organization would manage all of these interactions. But unlike recruiting a business to town, where there is always an organization like an economic development authority leading the process, it is hard to identify one specific organization that is a natural fit for recruiting people. In some communities, the local tourism office has had people recruitment thrust upon them, but that isn’t always ideal since tourism does not have the same goals.

Some of the regional development commissions and Initiative Foundations have taken on the responsibility, but it requires significant money, not only to cover their own expenses, but also to fund training and resources for local communities to help them participate effectively.

“It is a struggle to find and maintain funding for these initiatives,” says Hegland. “In order to be sustainable you have to move beyond grant funding and into a support system that allocates money on an annual cycle to develop and maintain content and support.”

It has been easier for UMVRDC to not rely on grant funding since they have a financial support structure in place that is funded through memberships from cities, counties and local chambers and EDAs, Hegland said, but for those who do have to rely on grant funding, it can become very much a patchwork of funding sources. So far, the only organization offering grants that specifically funds these types of initiatives is the Northwest Minnesota Foundation[4].

Perhaps the biggest hurdle of all, though, is overcoming the chronic and persistent narrative that rural regions are at best only for tourism and at worst, dying. These negative perceptions are hard to overcome and can lead to sometimes amusingly mixed messages.

For example, a Jan. 25, 2015, article in the Star Tribune painted a bleak demographic and economic picture of Greater Minnesota, especially for counties in the “L” of Minnesota, those bordering the Dakotas and Iowa.[5]

Ironically, the day before this article was released, another article appeared in the business section of the Star Tribune entitled “Rural counties in Minnesota leading economic recovery.”[6] And the section of the state that was leading the recovery? Counties in the “L” of Minnesota.

Confusing narrative like this makes recruiting people in urban areas more challenging, but so does confusing narrative among community members. The need for residents themselves to look at where they live and identify their local assets is an important piece of this puzzle.

New Ulm has been able to produce online and print material that market both tourism and community living. But Sarah Warmka, marketing specialist with the New Ulm Area Chamber of Commerce, acknowledges that the people of New Ulm must have an interest in promoting the assets of their own community. She heard a story from a recent visitor to the city.

“[A] visitor had asked a hotel employee where she could shop in New Ulm,” Warmka says, “and the employee said there is no place to shop in New Ulm and that she would have to drive to Mankato.”

The mission isn’t just about attracting people from outside the region, says West Central Initiative’s Schara, “but also to get people in the region to realize how great of a place it is to live.”

A shift in philosophy

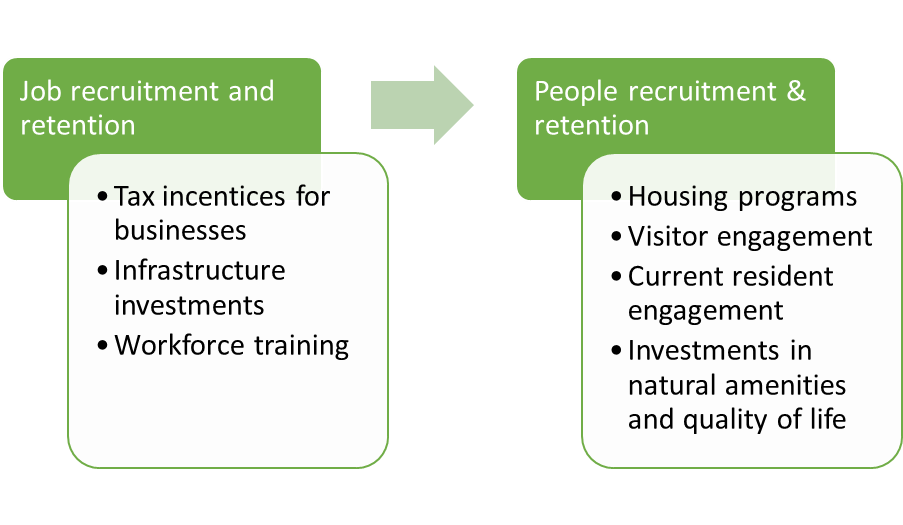

Since the 1970s, economic development strategies have been solely focused on bringing jobs to communities and regions. Tax incentives, cheap land, industrial parks, employee training centers, and even continued support of Minnesota State Universities and Colleges, which largely serve rural students and industries, were strategies rural leaders used to draw businesses out to their regions.

Rural regions are adapting again, but this time the strategies are shifting from recruiting jobs to recruiting people, focusing on housing programs, visitor strategies, current resident engagement, and quality of life factors (Figure 8).

As the need deepens and people recruitment initiatives pick up steam, rural Minnesota could use help and support, particularly from the Department of Employment and Economic Development. DEED has been the hub of economic development in the form of job creation and workforce development for decades. However, times have changed, and they have changed quickly. Job creation is no longer the primary problem that needs addressing in Greater Minnesota.

There are three areas where Greater Minnesota could use help to succeed in people recruitment.

- Building from scratch. Most Greater Minnesota communities are starting from square one when starting a people recruitment program, and building networks and resources takes money. The communities in these regions often don’t have the know-how to get a regional initiative started or the funds to hire someone who does.

- Lack of central organization. Unlike recruiting a business, where there is always an organization like an economic development authority leading the process, it is hard to identify one specific organization that is a natural fit for recruiting people in rural areas. In the Twin Cities area, one primary organization markets for one large population in one small geography. Greater Minnesota is in comparison made up of many large geographies containing many small populations. Central organization is important, but fitting together many disparate groups and stakeholders can be difficult.

- Promoting rural communities and regions is a new concept for many rural residents and leaders. It will require not just training in how marketing works, but helping residents change their own narratives about where they live.

To Rick Schara from West Central Initiative, support for people recruitment programs in Greater Minnesota is a no-brainer.

“What should legislators know? These initiatives are a workforce development strategy,” says Schara. “Support at the same level as other workforce development programs would be welcomed.”

[1] https://www.ruralmn.org/finding-work-or-finding-workers-pt1/

[2] For more info about this research, check out https://extension.umn.edu/economic-development/rural-brain-gain-migration

[3] http://www.exploreminnesota.com/industry-minnesota/research-reports/researchdetails/?nid=1660

[4] https://www.nwmf.org/programs/communities-thrive/

[5] Star Tribune, “Urban-rural split in Minnesota grows deeper, wider,” Jan. 25, 2015, http://www.startribune.com/urban-rural-split-in-minnesota-grows-deeper-and-wider/289688071/

[6] Star Tribune, “Rural counties in Minnesota leading economic recovery,” Jan. 26, 2015, http://www.startribune.com/rural-counties-in-minnesota-leading-economic-recovery/289682881/

[crpd_nested_box]

All Articles in this Series:

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 1

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 2

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 3

- Finding work or finding workers? Part 4

[/crpd_nested_box]