By Marnie Werner, Vice President, Research

April 26, 2023

Click here for a condensed two-page summary of this report.

Click here for a printable version of this report.

Click here to register for our upcoming webinar on Wednesday, May 3, 2:30 pm.

In January, Abdulla Gaafarelkhalifa was the only reporter left at the St. Cloud Times. His last day was Feb. 1, according to a January 2023 article from Axios,[1] and after he was gone, the Times, an award-winning newspaper with a history that can be traced back to 1861, was left with no reporting staff.

The Times is now being called a “ghost paper,” one of hundreds of newspapers around the United States that still exist, still put out a product, but have little to no staff and therefore little to no local content.

According to Penny Abernathy, the Knight Chair in Journalism and Digital Media Economics at the University of North Carolina, around 2,500 newspapers in the U.S. disappeared between 2005 and 2022, in recent years, at a rate of about two a week.[2] But like the Times, not every newspaper closes. Many have had their budgets cut and employees let go, especially in the newsroom. In Minnesota, the change can be illustrated in two numbers: 26% and 70%. According to the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development, between 2000 and 2021, the number of newspaper establishments (print-first, not online news outlets) in the state fell from 344 to 254, a 26% drop. Employee numbers, however, fell from 9,499 to 2,844, a 70% drop. Even more telling, the average number of employees per establishment went from 28 to 11.

Figure 1: The print newspaper industry has been shedding jobs steadily across the U.S. since 2000. Includes all print newspaper industry jobs, not just newsroom jobs. Data: MN Department of Employment and Economic Development

Rural Minnesota has few newspapers the size of the Saint Cloud Times. Most communities are served by small weekly newspapers, the primary sources of what could be called “hyperlocal” news, the news that is so local—city council meetings, school board meetings, community events—that no other news outlet would cover it if the local weekly paper disappeared. Among the approximately 120 Minnesota newspapers that disappeared between 2000 and 2022, around 40% of them were weeklies serving the Twin Cities suburbs, while the other 60% were Greater Minnesota papers. Dailies were affected as well, reducing their print editions from six or seven days a week to only two or three, and a handful longtime dailies closed altogether, including the International Falls Daily Journal.

Among Greater Minnesota’s weeklies, says Lisa Hills, executive director of the Minnesota Newspaper Association, most of the closures, especially among small rural weeklies, have been the result of mergers and acquisitions made by neighboring papers in an attempt to improve their economies of scale and therefore their bottom lines, making it possible to survive.

Every county in Minnesota has at least one newspaper (except Wilkin County, which technically has never had a newspaper since it’s served by the Wahpeton, N.D. paper), so the state doesn’t have any news deserts. In 2022, however, 17 counties had only one paper, including Olmsted County, which had four in 2000. In rural areas, that leaves many large territories covered by small papers with reduced staffs and a lot of news potentially going unreported.

Then in 2020, the pandemic was predicted to be the “extinction-level event” for local newspapers[3], but that hasn’t happened so far. Despite the dire situation, many rural counties in Minnesota still have two, three, four, even five weeklies. They may be operating on the edge, but they’re still operating, and some are even expanding. What does the future look like for these important sources of local news that can’t be found anywhere else? And what does the loss of this news do to communities when it comes to civic and political engagement?

Definition of a local paper for the purposes of this project.

Much of the research on newspapers has been done at the national level, and “local” papers are defined as newspapers that aren’t national, as opposed to The New York Times, the Washington Post, or USA Today. This report discusses the newspapers of Greater Minnesota, which are mostly weekly newspapers covering a city or group of cities, but not usually more than one county and the vast majority with a circulation of less than 5,000.

What happened to the newspaper industry?

The fact that the number of print newspapers in the U.S. fell 28%[4] between 2005 and 2022 is alarming, but circulation has in fact been dropping since at least the 1990s, caused by a combination of historic shifts in culture and technology that permanently affected newspapers’ ability to make money.

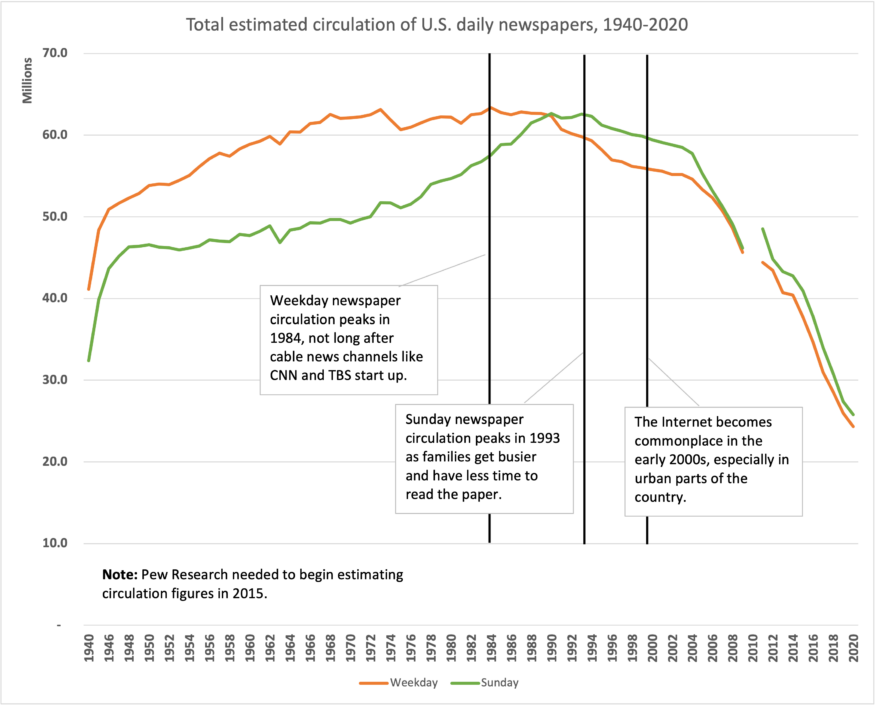

Figure 2: Weekday and Sunday circulation of U.S. daily newspapers has been shifting with changes in communications technology throughout the 1970s, ’80s, ’90s, and 2000s. Circulation among daily papers fell 40% nationwide between 2015 and 2021, while Sunday circulation was down 45%. Data: Pew Research Center.[5]

On the circulation side, reader attitudes and preferences have been shifting away from traditional print newspapers as a primary source of news in the community since the 1990s (see chart above). Over the years, different reasons have lured people away: the 1980s, when newspaper circulation peaked, saw the advent of nationwide cable channels like CNN and TBS, adding to the competition already coming from broadcast TV and radio. In the 1990s, as more mothers began working full time, families found less time to sit down and read the paper, especially as a leisure activity, according to Margaret Sullivan, a former editor at the Buffalo (New York) News and The New York Times and author of the book Ghosting the News.[6]

The 24-hour news cycle was already well in place by the time Internet access became commonplace, giving people the means of getting news anytime, anyplace, at their fingertips, especially after the advent of the smart phone in 2007. By 2011, a majority of the people responding to a Pew survey[7] that year didn’t regard their local newspaper as a key source of local news and information anymore. When asked how it would affect their ability to keep up with information and news about their local community if their local newspaper no longer existed, 69% of respondents indicated that it would have no impact (39%) or only a minor impact (30%) on their ability to get local information. The response was even higher among 18- to 29-year-olds: 75% said their ability to get local information “would not be affected in a major way by the absence of their local paper.” Heavy tech users responded similarly.

Yet, when asked in the same survey which news sources they rely on for that local information, “newspapers were cited as the most relied-upon source or tied for most relied upon for crime, taxes, local government activities, schools, local politics, local jobs, community/neighborhood events, arts events, zoning information, local social services, and real estate/housing.”

A broken revenue model.

Newspapers depend on revenue from three sources: classified ads, display ads, and subscriptions. Advertising provided the bulk of the revenue from the 1970s until 2020, when revenue from subscriptions finally exceeded revenue from advertising, according to the Pew Research Center (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Newspaper revenue from advertising paralleled revenue from circulation fairly closely through the 1950s and 1960s. Ad revenue then took off in the early 1970s, only to crash with the coming of the Internet and the Great Recession. Data: Pew Research Center. Includes all publicly traded companies.

While circulation among weekday newspapers peaked in 1984 and for Sunday subscriptions in the early ’90s, advertising revenue kept going strong simply because newspapers were still seen as the best way to get ads in front of potential customers. Then, in the early 2000s, two near-fatal blows hit newspapers: the launch of Craigslist in 2005 and the Great Recession in 2008.

When Craiglist appeared, it offered people a free alternative to classified ads. What perhaps really hurt newspapers was that Craigslist provided local sections, allowing people to advertise directly to their neighbors. Classifieds, which had made up about half of an average newspaper’s ad revenue, almost disappeared, seemingly overnight.[8]

The Great Recession of 2008-2009 then went on to decimate display advertising. Newspapers’ biggest advertisers in display ads—department stores and car dealerships—were already affected by the rise of the Internet as Amazon and other online retailers changed people’s shopping habits. Department stores were closing, especially in rural areas, and people increasingly shopped for cars online. Then the Great Recession forced the closings of hundreds of car dealerships across the country, often in smaller cities and towns, removing another source of ad revenue. More recently, the loss of advertising revenue from local restaurants and small businesses that closed during the early months of the pandemic was another major blow to advertising revenue.

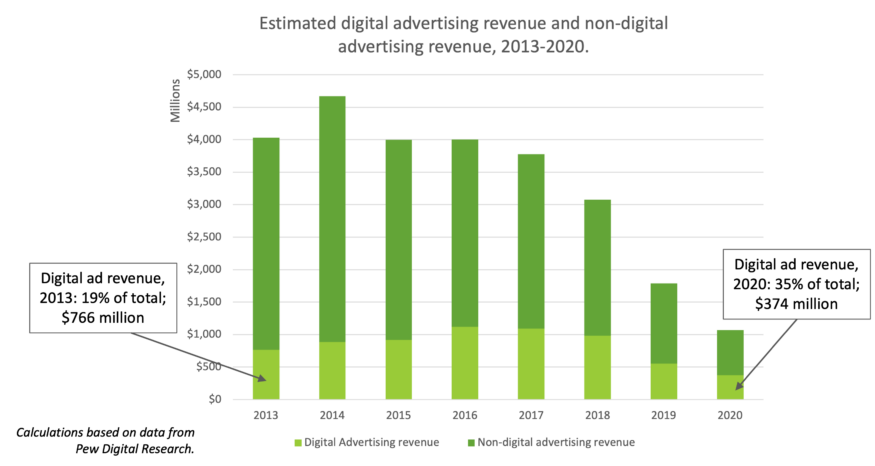

At the same time, though, tech giants like Facebook and Google appeared and began offering highly targeted advertising at a fraction of the cost of advertising in newspapers. Newspapers’ early response to this digital revolution was to move online with the hope of recapturing some of that advertising revenue through online readership. Unfortunately, the revenue from a single digital ad was (and is) so low that most print newspapers, especially smaller ones, haven’t been able to generate enough ad volume to come near replacing the lost revenue, even though digital ads continue to grow as a share of advertising revenue overall. In 2019 and 2020, the actual revenue from digital ads was only half of what it was in 2013, according to Pew Research (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Digital ad revenue for locally focused U.S. newspapers remained fairly constant between 2013 and 2020, but non-digital ad revenue has dropped off. Data: Pew Digital Research, “Local Newspapers Fact Sheet,” 2022.

So far, only large companies like Facebook and Google have been able to use digital ads effectively because of the sheer volume of ads they sell. Facebook and Google in particular use the information they collect on their billions of users, data like age, race, location, and perhaps most importantly, shopping habits, to put that advertiser’s ad in front of very specific viewers, thus raising the chances of it getting clicked.

“No amount of tinkering with free-market mechanics can restore the business fundamentals that sustained local news in the twentieth century,” wrote Timothy Karr, a researcher and media advocate, in the Columbia Journalism Review in 2022. The money newspapers made from advertising before 2000 “was due in large part to their unique ability to bundle local information with daily advertisements targeted to local audiences. This newsprint formula no longer functions in a media world where connections are instantaneous and attention is the main commodity[9].”

The disruption of the business model and resulting vulnerability of newspaper companies initiated a wave of mergers and acquisitions across the country as larger companies bought up smaller ones.

Today’s news industry is much more consolidated than it was twenty years ago. In 2000, only a handful of news groups existed in Minnesota, with most of their newspapers located in the Twin Cities. Today, Minnesota-based Adams Publishing Group/APG-ECM owns the largest number of Minnesota newspapers, at 38, according to the 2022 Minnesota Newspaper Association directory, followed by Forum Communications out of Fargo at 16, and CherryRoad, a New Jersey company, with 10.

A quick analysis of local papers from around Greater Minnesota shows how the newspaper landscape has changed here. We chose six local newspapers, all weeklies, and compared their print editions from October 1992, around the time circulations were peaking and well before the start of the Internet, to October 2022. As Table 1 shows, circulation dropped considerably during that time.

Table 1: Circulation has gone down for this selection of Minnesota weekly newspapers, even while the number of households in some communities has gone up.

Data: Minnesota Newspaper Association, U.S. Census.

Interestingly, the number of display ads did not change that much between 1992 and 2022, perhaps because four of the six papers in 2022 (and one in 1992) included special sections that more than doubled their display ads that week. At the same time, however, classified ads in 2022 were down more than 70% in all six papers.

Table 2: Number of news articles in 1992 and in 2022.

Data: Minnesota Newspaper Association, U.S. Census.

In rural communities, small businesses are the main advertisers, says Marshall Helmberger, owner of the Timberjay, covering Tower, Orr, and Ely in northeast Minnesota. The big-box businesses don’t advertise with his paper, he said, but the small local businesses do. As their owners age, however, the issue of selling the business comes along, and they have difficulty finding someone to buy it from them. These mom-and-pop shops often end up closing, Helmberger said, meaning the loss of another advertiser.

Eli Lutgens, the twenty-something owner of a newspaper in New Richland and a new startup paper in Waseca, sees advertising as giving advertisers the ability to hold him accountable for putting out a quality newspaper of substance. “Our advertisers also read the newspaper, because they’re all local, right?”

The case for “hyperlocal” news

An extensive amount of research has been done on how newspapers or the lack of them affect civic engagement. When we talk about civic engagement in this case, we’re referring “to the ways in which citizens participate in the life of a community in order to improve conditions for others or to help shape the community’s future[10].”

The common narrative around the loss of newspapers is that they provide important information that people need to be able to make good decisions (especially politically) in a democratic society. After all, Thomas Jefferson said, “The only security of all is in a free press,” while Alexander Hamilton wrote, “To watch the progress of such endeavors [corruption] is the office of a free press. To give us early alarm and put us on our guard against the encroachments of power. This then is a right of the utmost importance, one for which, instead of yielding it up, we ought rather to spill our blood.”

But in these days of instant news at our fingertips, are local newspapers still relevant? Their supporters argue that they are not just relevant, they are crucial, especially in rural areas, where they specialize in news no one else carries. Local papers deal in the “hyperlocal,” reporting on the news of a single city or school board. This hyperlocal level is where the individual taxpayer can have the most impact, and where there may be the least amount of official oversight. Addressing the St. Cloud Times’ current state of affairs, Dale Zacher, chair of the Department of Mass Communications at St. Cloud State University, commented: “This would be a great time to be involved in political corruption, because there’s nobody watching.”[11]

An informed public?

But what if individuals simply don’t care, or they find news so distressing, they avoid it, or they don’t believe the source is trustworthy?

Unfortunately, not everyone feels the need to be informed on their local news, or any news. University of Minnesota journalism professor Benjamin Toff found in his research that some people actively avoid the news because they find it too negative or they are overwhelmed by too many choices. News is seen as “emotionally taxing — a source of uncertainty and lack of control … in a complex and upsetting world.” At the same time, other respondents in his study “rejected the notion that being informed was a requirement for good citizenship.” As one respondent in Toff’s study put it, “‘It’d be nice to know what’s going on, but I don’t feel like I’ve missed out on anything[12].’”

Not everyone feels that way, however. Losing a small-market newspaper affects citizens’ access to information and news about political matters in their community[13]. The Warroad Pioneer closed in 2019, and it has not been replaced. In a recent article in the Grand Forks Herald, Warroad’s city administrator Kathy Lovelace stated that the “big hurdle is communication — how do you get things out to everybody?” The minutes from school board and city council meetings can be accessed online, she said, but “there is no in-depth reporting of agenda items and how they impact the community.” Some community groups in the city communicate their news on social media, “but older generations don’t use it as much and don’t know how to get information about what’s happening in the area[14],” Lovelace said.

The trouble with news on social media, too, is that it becomes self-selecting: people only see what they choose to see. If they want to follow the news of the local parent-teacher organization, they can through that group’s social media, but that reader is highly unlikely to also accidentally come across an article about new road projects that will be affecting property taxes or an opinion piece that challenges that reader’s political beliefs on a topic.

Today’s news environment puts a lot of stress on the news consumer to be their own fact-checker and researcher. “Instead of relying on a newspaper to interpret and verify information on behalf of the individual reader, the post-newspaper world places the onus on the individual to verify information, seek alternative perspectives, and band together with others to challenge information from those in power,” says Mark Nonkes in his 2020 review of research on newspaper closures. “With the closure of newspapers,” Nonkes says, “one wonders how individuals will be exposed to unanticipated information about their community that may expand their perspective, maintain their sense of belonging, and/or assist them in problem solving.”[15]

Researcher Joshua Darr, who studied the impact the type of news can have on readers, found that when local newspapers close, instead of finding another local option, people tend to get their news from national outlets. The problem, Darr says, is that people then stop paying attention to local issues and focus on higher-level, more nebulous issues. “When people read news about their neighborhoods, schools and municipal services, they think like locals. When they read about national political conflict, they think like partisans,” Darr concluded[16].

Darr notes that in July 2019, the executive editor of The Desert Sun in Palm Springs, Calif., conducted her own experiment after reading Darr’s research: “She decided to drop national politics from the opinion page for a month,” Darr said. She ran “just op-eds and letters about California, Palm Springs and the surrounding Coachella Valley.”

In that month, the paper was suddenly covering more local issues in greater depth, as were the letters and opinion pieces. Partisan arguments disappeared from the paper, while local issues like architectural preservation and traffic congestion increased. Those problems may sound trivial, Darr says, but “these [local] topics were not about Democrats and Republicans — they were about Palm Springs issues.” [17]

We have spirit

In rural areas, including in Minnesota, there may be no greater example of civic engagement and community cohesion than in high school sports. In Warroad, Lovelace lamented the loss of high school sports coverage. “‘It’s odd to me to think this whole age of kids are never going to get to see their picture in the paper,’ Lovelace said. ‘As a parent, that was a big deal for me.’” Mark Chamernick, Warroad High School’s athletic director, agreed. “‘Our girls hockey team just won the state championship — it would be nice to have clippings to compare to when they won it in 2010.’”[18]

Someone who understands this most local of local coverage is Eli Lutgens, the owner and publisher of the NRHEG Star Eagle (NRHEG stands for New Richland-Hartland-Ellendale-Geneva, the name of the school district) and the new Waseca County Pioneer. They are print-first newspapers, and Lutgens makes a special effort to cover school news, especially sports.

“We started covering Waseca sports to begin with because I felt that was the first step necessary to opening a newspaper,” especially in an area that already had an established paper, the Waseca County News. Lutgens likes small town news because “you get much more intricate, intimate content. The stories can be quite literally about your neighbors. You can go to any person in any small towns and write about them, and they will have a story,” Lutgens said in an interview.

Sports are good for the town and good for the paper. “The thing about our small town is that all of the kids are very, very aware of the newspaper, because their grandmothers keep scrapbooks,” Lutgens said. “I have kids that come in routinely throughout the year asking for photos that I took at sporting events that they saw in the paper, and they want the extras.”

School sports aren’t the only element making up community cohesion: there are also all the many community events, church fundraisers, 4-H and FFA, county fairs, Lions and Kiwanis, VFW and American Legion.

“We provide what Facebook can’t,” says Jason Brown, publisher of the Long Prairie Leader. “Facebook can’t be on the garage wall at the graduation party. Facebook isn’t there on the first day of kindergarten.”

Small communities are the ones being left in the lurch as newspapers have closed around him, Brown says. “It’s left the smaller communities hanging. Smaller surrounding communities felt like they were not a priority. They have their own schools, and they wanted coverage.” Brown is expanding the Leader’s reach to cover those school districts and cities, and he also started a Spanish-language edition for the city’s significant and growing Latino population when he realized how disconnected they were from city and community news.

The biggest headache

But with all these ventures, Brown says, staffing “has been interesting.” Finding staff is the big problem, especially for small newspapers. Hills says they have never had so many open positions on the Minnesota Newspaper Association’s statewide job listings service.

One problem is of course revenue. Newspapers struggle to make enough money to support the array of reporters and editors that they once did, and the low pay is not attractive to young journalism students. When asked what would help newspapers attract recent journalism school graduates, Jennifer Moore, head of the journalism program at the University of Minnesota, Duluth, stated: “Pay them. Many can’t live on what they’re paid.”

There’s also perception. Lutgens relates the story of a friend working for a paper owned by one of the larger newspaper companies in the state. At an editorial meeting, this friend suggested that, to gain readers, they should cover more local news—Boy Scouts or Lions’ Club events.

“He was laughed out of the room and told by all the college-graduate journalism students that that wasn’t real journalism,” Lutgens said.

Key takeaways

The practical question in front of rural papers today is how to cover large areas while being supported financially by a small customer base, especially in an environment of rising costs and an atmosphere of doom surrounding the industry. While journalism as an entity is alive and well, it’s shifting to alternate—namely digital—platforms[19], making rural journalism’s future touch and go. Here are some key points that came out of our research.

1: Don’t write off small community newspapers yet. Although a large number of newspapers have either closed or merged into other news organizations, the demand and need are there, and new papers are still starting up. The old advertising-first business model is in dire straits as the pressure to move everything online continues, but remaining a physical product could be a competitive advantage for newspapers, “bringing people together in time and space[20].”

When the Osakis Review’s parent company, Forum Communications, shut that paper down during the pandemic, city officials approached Jason Brown at the Long Prairie Leader and asked him to apply to make the Leader the newspaper of record for the city. After what turned into some long conversations, Brown agreed, but he also decided to open a new paper, the Osakis Anchor. Eli Lutgens started the Waseca County Pioneer because he was unhappy with the incumbent paper in the county. The Rainy Lake Gazette was started by CherryRoad Media, a large multi-state media company, to replace the International Falls Journal (formerly Daily Journal) when it closed in June 2021.

People will buy and subscribe to papers they believe are offering quality content and serving their audience, publishers have said. Yes, some communities have simply become too small to support their own paper financially, but neighboring newspapers could cover them if their owners thought they could produce sufficient revenue to hire even one additional reporter, even part time. Even small investments could make a big difference, and therefore public and/or private grants could help local newspapers fill news voids that have been vacated by other papers or are being covered by ghost papers.

2: Don’t expect digital to save the day, at least not any time soon. It’s not just that the rural population tends to skew older, and older readers tend to like print. Pew Research in fact found in 2022 that 49% of Americans age 65 and older got their news at least sometimes from print newspapers. However, 85% said they also got their news from television and 67% also reported using digital devices. When asked where they preferred to get their news from, though, only 11% of seniors said they preferred to get their news from print publications; 56% preferred to get it from television and 25% preferred digital devices[21].

That seems to go against the common narrative until we consider two things: First, rural newspapers are less likely to be online or to have sophisticated news web sites, largely because small rural newspapers are unlikely to have the money to invest in digital platforms and technical assistance and because rural communities are less likely to have the digital infrastructure of urban and suburban communities. Second, rural residents are less likely to have access to broadband, again because of a lack of digital infrastructure. Therefore, as Pew points out, for rural residents, it may not be a matter of what they are doing when they look for news, but what they can do.[22]

Some entities are working on this. Wick Communications, the parent company of the Fergus Falls Journal, is currently testing its own proprietary social media platform, called NABUR—Neighborhood Alliance for Better Understanding and Respect—where people can have conversations and discuss local issues in a safe, moderated setting. Part of its development is figuring out how to monetize it, said the Journal’s publisher Ken Harty. “Smaller papers don’t always have the money to invest in digital,” he said.

On the philanthropic and venture capital side, Glen Nelson Center at American Public Media Group, parent organization of Minnesota Public Radio/American Public Media, awards grants and makes investments to media organizations through two programs. The Horizon Fund invests in for-profit media startups that “bridge diverse and disparate communities, share trustworthy information, promote civil discourse, and give audiences new tools to gain insight from others.” The Next Challenge for Media and Journalism fund is a nationwide competition looking for both for-profit and non-profit startups with less than $1 million in annual revenue that “will reinvent media in the coming decade.”

In the meantime, the discussion continues on how best to bring the news to “the digitally unconnected and the disengaged.” [23]

3: Diversfied revenue streams. Revenue doesn’t have to come from advertising alone. A recurring theme from the editors interviewed was that people will pay for “quality,” an important point since nationwide, subscriptions now account for more newspaper revenue than advertising, according to Pew Research. Especially, as the commercial makeup of rural Main Street continues to change, newspapers have to be willing to look for revenue sources beyond advertising. Organizing sponsored events is an option being used by the Fergus Falls Journal, says Harty: Athlete of the Week, the Golden Loon Awards for high school art students, and Yard of the Week are just some of the events organized by the Journal and sponsored by local businesses and organizations.

Operating as a 501(c)3 nonprofit opens up the possibilities of donations that are tax-deductible for the donor. MinnPost was one of the first nonprofit news organizations, and what they learned early on was “the importance of having a diverse revenue stream,” said Tanner Curl, MinnPost executive director. MinnPost earns revenue from advertising, sponsorships, and grants, but individual gifts—donations—are the most significant, making up about two thirds of their annual revenue, he said.

Funding for nonprofits is more difficult to come by in rural areas, however. Abernathy asked in her 2022 State of Local News report, “Even though philanthropic organizations have significantly increased support of local news in recent years, most of the funds are currently being dispensed in the media-rich, urban areas[24].” The Minnesota Council on Foundations’ 2021 report on philanthropic giving in Minnesota backs up this assertion: while 49% of philanthropic giving by Minnesota-based foundations went to the Twin Cities area and 41% went outside of Minnesota, just 8.6% went to Greater Minnesota[25]. With this kind of a situation, “how can for-profit and nonprofit funding be reallocated to support the revival of local news in media-poor communities[26]?” Abernathy asks.

4: Finding staff. As discussed earlier, finding and retaining reporters and other staff is one of the biggest problems holding back enterprising newspapers. One advantage that small community newspapers may have, though, is that their reporters and other staff don’t need degrees or other formal credentials—they can be trained on the job, and would-be reporters don’t necessarily have to give up their day job. Jason Brown at the Long Prairie Leader said he can’t afford a full-time reporter at $30,000 to $50,000 a year plus benefits, but he has built a reliable staff of part-time freelancers and volunteers who work their day jobs, then cover meetings and sports in their off hours. It’s about finding the right people, says Brown. “If they’re willing to work, I’m willing to train them and support them to be successful.”

One possibility for getting over this hurdle for rural newspapers could be an intentional commitment to developing online courses that teach people in the community how to be reporters, ad sales people, and newspaper managers.

The Minnesota Newspaper Association’s nonprofit arm, Minnesota News Media Institute (MNI), has already started in this direction by partnering with Bethel University to offer Citizen Journalist University, a training course for people who would like to be community journalists. The program involves a mixture of working and retired journalists, publishers, and editors, covering basic journalism practices, style, and ethics, sports reporting, how you determine what goes on the front page. MNI also helps MNA-member newspapers with the cost of hiring interns.

5: Government involvement. Government has supported newspapers for decades by paying to have city council meeting minutes, court notices and other legal notices published in what is called the “newspaper of record” or “official newspaper” for that jurisdiction. Legal notices are usually a small but steady stream of income for papers.

In recent years, however, bills have been introduced at the federal level and state level around the country aimed at helping maintain the health of local newspapers.

In Washington State, for example, legislation was proposed that would eliminate the business and occupation tax on local newspapers and digital-only news outlets. As proposed, newspaper publishers, along with online outlets with two to fifty employees would be eligible. The break would expire in 2035[27].

Two bills being considered in Congress are taking two very different paths in their attempts to help newspapers with revenue.

Sen. Bill 673, Journalism Competition and Preservation Act of 2022.

Sponsored by U.S. Senator Amy Klobuchar, the bill has bipartisan co-sponsors, including Sens. Lindsey Graham and Cory Booker. The central feature of the bill gives newspaper outlets a temporary exemption from federal antitrust laws to allow them to work together to collectively bargain with the large social media companies for compensation for the news content those companies present on their platforms. Google and Meta (Facebook) are opposed to the bill, saying that the exposure they give newspapers by bringing their content up in search results is adequate compensation[28]. The latest version of the bill is making its way through the U.S. Senate. The bill specifies “eligible providers” as news outlets with fewer than 1,500 full-time employees.

H.R. 3940, Local Journalism Sustainability Act

This bipartisan bill would allow individuals and businesses to claim tax credits (up to $250) for subscriptions they purchase to local newspapers and media, while qualifying small businesses would be allowed tax credits for the cost ads purchased and placed in local newspapers and media. The bill would also give local newspaper employers a payroll tax credit for wages paid to employees working as local journalists.

“All this points to a need for new policies to address the gap” in revenue, says Abernathy in her 2022 report. Besides considering tax credits, states are also forming bipartisan task forces to identify communities at risk of losing their local news sources and to brainstorm policies and funding avenues that would help preserve papers in communities[29].

“The challenge will be getting public funding to the communities and news organizations that need it most,” says Abernathy.

The future of rural newspapers?

By the time the St. Cloud Times’ last reporter left, Fargo-based Forum Communications had launched St. Cloud Live, an online news outlet. It’s now staffed by, among others, Abdulla Gaafarelkhalifa.

While the principle of news reporting stays the same, the business side is in the middle of a massive transition caused by the massive shifts in culture, including of course the Internet. Can newspapers survive this transition? The health of rural communities says they need to. Abernathy condenses the problem of disappearing newspapers into one sentence: “Without a coordinated and targeted response among individuals, organizations and institutions, the nation faces the prospect of local news being available only in affluent communities, where residents can afford to pay for it[30].”

But so far, even after two decades, the response has not been coordinated or targeted, and no blanket solution has been found that cracks the revenue nut. Meanwhile, small rural newspapers continue to disappear or get absorbed by larger chains or simply struggle to get the news covered with fewer people. As with most rural issues, the solution probably won’t come in one grand initiative but perhaps in the cooperative efforts of state and local, public and private. How do we develop and support these efforts so that the news people need continues to flow? What is not an option is to sit back and do nothing. As Ken Harty pointed out, “If you do nothing, you’re not going to make it.”

Correction: The original version of this report incorrectly stated that the Mesabi Daily News had closed. The Mesabi Daily News merged with the Hibbing Daily Tribune to become the Mesabi Tribune.

[1] Kennedy, Audrey. “St. Cloud Times Just Lost Its Last Remaining Reporter.” Axios, January 24, 2023.

[2] Abernathy, Penny. “The State of Local News 2022.” The State of Local News. Northwestern University, June 29, 2022.

[3] Adam Gabbat. “Local Journalism Is on Its Knees – Endangering Democracy. Who Will Save It?” The Guardian, July 28, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/media/2020/jul/28/local-journalism-democracy-us-newspapers.

[4] Abernathy, Penny. “The State of Local News 2022.” The State of Local News. Northwestern University, June 29, 2022. https://localnewsinitiative.northwestern.edu/research/state-of-local-news/report/.

[5] Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. “Newspapers Fact Sheet,” June 29, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/newspapers/.

[6] Sullivan, Margaret. Ghosting the News: Local Journalism and the Crisis of American Democracy. New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2020.

[7] Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. “Part 3: The Role of Newspapers,” September 26, 2011. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2011/09/26/part-3-the-role-of-newspapers/.

[8] Reinan, John. “How Craigslist Killed the Newspapers’ Golden Goose.” MinnPost, February 3, 2014. https://www.minnpost.com/business/2014/02/how-craigslist-killed-newspapers-golden-goose/.

[9] Karr, Timothy. “The Future of Local News Innovation Is Noncommercial.” Columbia Journalism Review, March 18, 2022.

[10] Adler, Richard P., and Judy Goggin. “What Do We Mean By ‘Civic Engagement’?” Journal of Transformative Education 3, no. 3 (July 2005): 236–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344605276792.

[11] John Reinan. “Deep Staff Cuts Leave St. Cloud Times a ‘Ghost Paper.’” Star Tribune, Dec. 9, 2022.

[12] Toff, Benjamin, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. “How News Feels: Anticipated Anxiety as a Factor in News Avoidance and a Barrier to Political Engagement.” Political Communication, September 14, 2022, 1–18.

[13] Nonkes, Mark. “When a Small Market Newspaper Closes.” Emerging Library & Information Perspectives, 9/11/2020

[14] “No News Isn’t Good News in Warroad, a Town That Grapples with the Loss of Its Newspaper – Grand Forks Herald | Grand Forks, East Grand Forks News, Weather & Sports.” Accessed April 3, 2023. https://www.grandforksherald.com/news/minnesota/no-news-isnt-good-news-in-warroad-a-town-that-grapples-with-the-loss-of-its-newspaper.

[15] Nonkes, Mark. “When a Small Market Newspaper Closes.” Emerging Library & Information Perspectives, 9/11/2020

[16] Darr, Joshua. “Local News Coverage Is Declining — And That Could Be Bad For American Politics.” FiveThirtyEight, June 2, 2021.

[17] Darr, Joshua. “Local News Coverage Is Declining — And That Could Be Bad For American Politics.” FiveThirtyEight, June 2, 2021.

[18] “No News Isn’t Good News in Warroad, a Town That Grapples with the Loss of Its Newspaper – Grand Forks Herald | Grand Forks, East Grand Forks News, Weather & Sports.” Accessed April 3, 2023. https://www.grandforksherald.com/news/minnesota/no-news-isnt-good-news-in-warroad-a-town-that-grapples-with-the-loss-of-its-newspaper.

[19] Forman-Katz, Naomi, and Katerina Eva Matsa. “News Platform Fact Sheet.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project (blog), September 20, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/news-platform-fact-sheet/.

[20] Nonkes, Mark. “When a Small Market Newspaper Closes.” Emerging Library & Information Perspectives, 9/11/2020

[21] Forman-Katz, Naomi, and Katerina Eva Matsa. “News Platform Fact Sheet.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project (blog), September 20, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/news-platform-fact-sheet/.

[22] staff, Pew Research Center: Journalism & Media. “How People Get Local News and Information in Different Communities.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project (blog), September 26, 2012. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2012/09/26/how-people-get-local-news-and-information-different-communities/.

[23] Abernathy, Penny. “The State of Local News 2022.” The State of Local News. Northwestern University, June 29, 2022. https://localnewsinitiative.northwestern.edu/research/state-of-local-news/report/.

[24] Abernathy, Penny. “The State of Local News 2022.” The State of Local News. Northwestern University, June 29, 2022. https://localnewsinitiative.northwestern.edu/research/state-of-local-news/report/.

[25] “Giving in Minnesota 2021 Report.” Minnesota Council on Foundations, 2022.

[26] Abernathy, Penny. “The State of Local News 2022.” The State of Local News. Northwestern University, June 29, 2022. https://localnewsinitiative.northwestern.edu/research/state-of-local-news/report/.

[27] Dudley, Brier. “Free Press Roundup: Ferguson Proposal, Tri-Cities Purchase.” The Seattle Times, January 11, 2023. https://www.seattletimes.com/opinion/free-press-roundup-ferguson-proposal-tri-cities-purchase/

[28] The Seattle Times. “Washington Publishers Say Journalism Bill a Potential Lifesaver,” September 2, 2022. https://www.seattletimes.com/opinion/washington-publishers-say-journalism-bill-a-potential-lifesaver/.

[29] Abernathy, Penny. “The State of Local News 2022.” The State of Local News. Northwestern University, June 29, 2022. https://localnewsinitiative.northwestern.edu/research/state-of-local-news/report/.

[30] Abernathy, Penny. “The State of Local News 2022.” The State of Local News. Northwestern University, June 29, 2022. https://localnewsinitiative.northwestern.edu/research/state-of-local-news/report/