November 2021

Kelly Asche, Research Associate (CRPD)

Neil Linscheid, Educator – Community Economics (U of MN Extension)

Ryan Pesch, Educator – Community Economics (U of MN Extension)

For a printable version of this report, click here.

Online sales have permeated everyday life and their impacts stretch beyond convenience of shopping. Local leaders see the evidence every day in their communities: more and more delivery trucks going down their roads, stopping at their neighbors’ or their own houses, dropping off products that were once maybe purchased in their own or a nearby community.

They’re also seeing the closure of retail storefronts. They hear about their local landfills reaching capacity earlier than predicted due to the higher amounts of waste from household deliveries. And after decades of watching businesses move away from their communities to concentrate in economic centers, rural leaders are left wondering if this is the “next shoe to drop” in their community’s economic demise. And at the same time, leaders in the economic centers that have benefited from decades of shopping behaviors shifting in their favor now worry that online sales are a threat to the revenue they’ve been relying on themselves.

In some ways, the data confirms what appears to be going on in our communities. Although still a modest percentage of total retail sales (~10%), online sales from out-of-state sellers are growing significantly, and there is no indication this growth will subside. The impact this shift is having on traditional brick-and-mortar retailers is pronounced. It’s digging into profits and forcing many to close stores or to at least change their investment patterns.

Concerns about the impact this shift in shopping behaviors will have on local government revenues center on two revenue sources: sales tax revenue for cities and counties that implement a local-option sales tax and property tax revenue from commercial properties.

Fortunately, due to the Supreme Court’s recent ruling allowing states to force out-of-state retailers to collect and remit sales taxes, as well as the hard work by the Department of Revenue to create processes ensuring taxes are going to the correct jurisdictions, our rural areas are not seeing any sort of negative impact on sales tax revenues. In fact, academic research shows that our rural areas of the state may stand to benefit from the shift in shopping behaviors.

Revenues from property taxes are also, so far, not being impacted. Although the number of retail firms has declined dramatically, these properties are a relatively small share of the overall property tax revenue pie. Coupled with dramatic growth in other property tax classes, rural areas have actually experienced the most significant growth in property tax revenues in the state.

Although this is a good news story so far, it will be important for the state to gather data and analyze them in new ways in order to keep an eye on what promise to be shifting and unpredictable trends. We are still early in this story, and it’s likely to be a long novel. It would be best for the state to help our communities be the editor of their stories rather than victims of another surprise shift in consumer patterns.

What is the Amazon effect?

The “Amazon Effect” is the generic label used to sum up the powerful disruption e-commerce has caused in the retail economy over the last twenty years. Research has identified the main disruptions putting downward pressure on retail prices, which in turn lead to decreased profits for brick-and-mortar retailers:[1]

- Price flexibility and uniform pricing

Price flexibility refers to the ability to adjust prices easily and quickly based on negotiation between buyers and sellers and changes in demand and supply. The rise of e-commerce has generated more flexibility since the technology now makes it possible to change prices instantly, and since 80% of shoppers now check prices online before making a purchase, brick-and-mortar retail has had to be nimbler in their pricing to keep up with online stores.

Interestingly, while prices have become more flexible, uniform pricing—when a company charges a universal price for its goods or service regardless of location—has become significantly more common. In the past, retailers often charged different prices in different regions depending on demographic and economic variations among the locations. Rural areas tended to be charged higher prices because of the extra cost of shipping and general economies of scale. Uniform pricing is more common now, which is great for rural consumers but can be hard on retailers.

- The rise of experience-based shopping

To draw customers in, brick-and-mortar retail stores are focusing more on in-store experiences. This emphasis on destination includes events, green space in retail centers, larger showrooms, and free giveaways. Retailers once relied heavily on marketing and promotion, but now they must spend more in other areas to draw people out of their homes and through their doors.

- Incorporation of technology in brick-and-mortar retailers

Retailers are incorporating online technology at an increasing rate in order to create a smoother experience similar to an online shopping experience. The pandemic has accelerated this move, with traditional brick-and-mortar stores offering online purchases, delivery options, and stay-in-the-car pick-up options for their customers.

These disruptions have forced brick-and-mortar stores to make significant investments in technology, store layouts, promotion, events, and staffing while also feeling the downward pressure of lower markups. They are essentially doing more with less.

Of course, not all brick-and-mortar retailers are able to compete in the middle of all this change, and therefore the last twenty years have been a time of attrition. And though retail has always been a fast-changing, competitive market, it’s understandable that the recent closures of major retail businesses have local leaders worried about their tax revenues. However, a dive into the data shows that local revenues may be just fine, at least in the near term.

Reasons for concern

Major disruptions in retail can impact two sources of local tax revenues:

- Local-option sales tax revenues, and

- Property tax revenues from brick-and-mortar retailers.

Minnesota hasn’t been immune to the growth in online sales. Although e-commerce is still a modest fraction of total retail business, its growth—and its impact on shopping behaviors—has been explosive, making local leaders nervous.

The Minnesota Department of Revenue reports the total sales, tax revenues, and number of establishments from outside the state that have remitted sales taxes on sales to Minnesota residents. These figures are published in statewide reports as “non-Minnesota.” Although we can imagine that much of this activity is “e-commerce,” it’s not a perfect one-to-one extrapolation because the data include both non-Minnesota online retailers and traditional brick-and-mortar retailers located outside of Minnesota selling to Minnesota residents.

Figure 1 gives an indication of the growth of e-commerce by showing the change in taxable retail sales occurring in Minnesota between Minnesota-based retailers and non-Minnesota-based retailers. Between 2010 and 2019, taxable retail sales for non-Minnesota-based retailers grew by 171% compared to 32% for Minnesota-based retailers.

Figure 1: Growth in non-Minnesota retail taxable sales dwarfs that of MN retail taxable sales. This shows the influence that online retail is having in the retail consumer market. Data: MN Department of Revenue – MN Sales and Use Tax

Figure 2 shows that by 2019, taxable sales from non-Minnesota-based retailers reached 13.2% of the total retail pie, up from 7% in 2010. Although still a relatively modest share of total retail sales, nothing indicates this trajectory will slow down.

Figure 2: By 2019, taxable retail sales by non-Minnesota based retailers accounted for over 13% of total taxable retail sales in the state. Data: MN Department of Revenue – MN Sales and Use Tax

Impact on local-option sales tax revenues

With the data confirming what people are seeing in their communities and nationwide—that online sales are a growing part of the consumer pie—the next question is how this shift is impacting sales and property tax revenues.

Sales taxes

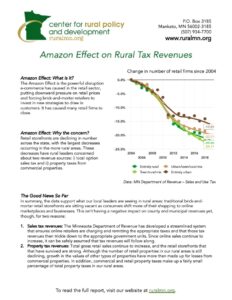

Fortunately, the trends in rural Minnesota indicate that shifts in shopping behaviors haven’t had a negative impact on revenue from local-option sales taxes, which is good news considering the impacts of other significant market disruptions like the Great Recession. Figure 3 shows the change in local sales tax revenues since 2004 for select cities around the state. We included communities with the longest histories of implementing a local-option sales tax: those that had the tax in place for its first full year between 2004 and 2007. The chart shows consistent growth in revenues across all regions of Minnesota, indicating that the rise of online sales did not seem to have a negative impact on revenues. Any negative impacts from online sales would have likely been more obvious.

Figure 3: The change in local-option sales tax revenue for cities that implemented the tax between 2004 and 2007 shows continued growth. Although some cities are experiencing more growth than others, the rise of online sales does not seem to be negatively impacting revenues. Data: MN Department of Revenue – Minnesota Local Sales and Use Tax

Counties have been allowed to charge a local sales tax for transportation projects only since 2014, giving us fewer data points to work with. However, Figure 4 shows a trend similar to that of the cities: the rise of online sales did not seem to negatively impact sales tax revenues. The trendlines continue to go up in a very consistent pattern.

Figure 4: Similar to cities charging local sales tax, local-option sales tax revenues for counties grew between 2014 and 2019. Again, it seems that the rise of online sales taxes didn’t impact sales tax revenues negatively. Data: MN Department of Revenue – Minnesota Local Sales and Use Tax

Although the data points are limited and can be a bit inconclusive, they do align with ongoing research across the nation showing that commercial and retail sectors have felt significant effects from the growth in online sales, but those impacts haven’t translated into negative impacts for local governments in terms of revenues. In addition, other research across the country has shown that as this trend continues, the most rural areas of the country may be positioned to benefit the most since more residents will stay local and order their products online rather than export their tax dollars to neighboring local governments.[2] Why is this the case?

Making it work

Although a consumer may not think about sales taxes much beyond what they pay, the process in which a business charges and remits sales taxes is complex, especially when the transaction takes place online.

For example, if someone orders products online at home from Walmart but chooses to pick up those products at Walmart’s physical store in a different community or county, which sales tax is charged? The sales tax in effect where the person lives or the sales tax where the person picks up the product? And on which products?

The Supreme Court addressed this issue and the Minnesota Department of Revenue developed the framework to answer the question of just how local governments can receive the correct sales tax revenue. These efforts mitigated any negative impacts the rise of online sales may have had had they not stepped in.

Supreme Court: Interpreting the Constitution in a changing economy

The battle for states to force out-of-state businesses to collect and remit state sales taxes started mostly in the 1960s and has largely taken place at the Supreme Court. The argument centers around two clauses in the U.S. Constitution: the Interstate Commerce clause and the Due Process clause.

The Interstate Commerce clause states that states are not allowed to interfere in each other’s flow of commerce. One state demanding that a business in another state start paying sales taxes on sales made in that first state could be construed as interfering in the second state’s commerce since collecting sales taxes would be an expense to the business and it could conceivably lose customers.

According to the Due Process clause, businesses that meet the minimum level of “contacts” in a state are subject to that state’s laws. Therefore, an online business like Amazon could be required to collect sales taxes from sales in any state where Amazon has a physical presence, like a warehouse.

The Due Process Clause worked for a while, but as e-commerce grew, it became clear that the lost sales taxes from companies without a nexus in Minnesota were far outstripping the sales taxes collected from companies that did.

By 2010, online sales were having significant market and public policy impacts by creating a disadvantage for brick-and-mortar retailers. These stores were not required to charge and remit sales taxes, which in turn reduced tax revenue to local services.[3]

The Supreme Court agreed that it was time to revisit the issue. In the 2018 South Dakota vs. Wayfair case, the Court overruled its previous physical presence rule and replaced it with an “economic nexus” rule.

The state of South Dakota argued that an online or out-of-state retailer that made $100,000 in sales of goods or services or engaged in 200 or more separate transactions for the delivery of goods or services in South Dakota had an “economic nexus” in the state and therefore had to collect and remit South Dakota sales tax.

The Court ruled this change was now possible due to a few important developments:

- Online, out-of-state sellers’ pervasive, virtual presence satisfied the due process clause;

- New software made it easy for firms to track and collect sales tax, even in states with many different local tax rates; and

- Small firms with few transactions were reasonably protected since the law was not retroactive and included clear rules and thresholds.

Since that ruling, 43 of the 45 states with statewide sales taxes have started collecting sales taxes from online sellers, many of them closely following South Dakota’s definition of an economic nexus.[4]

MN Department of Revenue: Making it easy to collect and remit the correct sales tax

Even before the Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling, the Minnesota Department of Revenue was hard at work establishing guidelines for sales tax collection and remittance for online retailers. A few online retailers had a physical presence in Minnesota already (e.g., the Amazon distribution center), which meant the state could enforce tax collection and remittance rules on those firms even though transactions were online. After the South Dakota vs. Wayfair ruling, sales tax laws now applied to firms with no physical presence in Minnesota whose “total sales over the prior 12-month period total either:

- 200 or more retail sales shipped to Minnesota, and/or

- more than $100,000 in retail sales shipped to Minnesota.”[5]

With the “who” in “who must collect and remit sales tax” (firms) now settled, three key questions guide a firm in determining if and how much sales tax it should collect:

- Is the product or service being purchased exempt from sales or use taxes in Minnesota?

- Where did the customer receive the taxable product or service?

- Does the nexus jurisdiction have a local sales tax in place?

As a member of the Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board, Inc., an organization developed in response to Supreme Court rulings about taxation on out-of-state sellers, Minnesota has made significant efforts to make the information for the three questions above easy to find.

In response to question 1, the Minnesota Department of Revenue provides a matrix detailing which products are exempt from sales and use tax and a spreadsheet of all jurisdictions (with corresponding zip codes) with a local-option sales tax in place.

For the second question, the Department of Revenue provides directions on how to approach “where the product or service was received”:

General sourcing rules have an order. Start with rule 1. If it does not apply, go to rule 2. When rule 2 does not apply, go to rule 3. The majority of sales fall into rules 1, 2, or 3.

- Seller’s Address – when the purchaser picks up the product at the seller’s location, charge tax based on the business location.

- Delivery Address – when the customer directs the seller to ship the product or service to a location, charge tax based on the location where the product or service is delivered.

- Billing Address – when 1 or 2 does not apply, charge tax based on the customer address in your records.

- When the above do not apply, charge tax based on the customer’s address obtained during the transaction (for example, the address on a customer’s check).

- When an address is not available, charge tax based on the address from where the item was shipped or the service was provided.[6]

The following provide some different scenarios that can be confusing when determining sales tax. It’s also worth checking out the endnotes, which link to Minnesota Department of Revenue fact sheets providing detailed information.

Scenario 1: Purchasing an online gift card

A consumer purchases a gift card from an online retailer.

This purchase is not taxed.[7] Instead, when the consumer uses the gift card the appropriate taxes on the product or service being purchased are collected. Gift cards are thus treated as cash and would follow the questions laid out above (was it used for a taxable product, where was it received, and does the jurisdiction have a local sales tax.

Scenario 2: Purchasing a product but having the product shipped to a friend in a different state

The sales taxes for your friend’s location are due, not the Minnesota sales taxes. Taxes are collected and remitted following your friend’s state’s rules.[8]

Scenario 3: Purchasing a product online from your home but picking it up in person in a different community in Minnesota.

The local taxes at the location where you pick up the item are due.[9]

Scenario 4: Digital Products – digital photos and drawings

This type of digital product is exempt from sales tax.[10]

Scenario 5: Digital Products – e-book

A sales tax is applied on this product based on the purchaser’s address the seller has on file.[11]

This process clearly identifies the appropriate jurisdiction and sales tax rate, which ensures that the shift to online sales won’t negatively impact sales tax revenues for state and local governments. However, it doesn’t necessarily negate any impacts due to the actual shift in consumer patterns, something that does raise concerns among our tourism-rich areas and economic centers spread throughout rural Minnesota. Many governments that opt in to a local sales tax have similar characteristics: they typically already bring in a lot of people from outside the community to shop and pay the local-option sales tax. Essentially, they import tax dollars.

Although it’s still relatively early, academic literature has attempted to answer the question of how online sales are affecting these regions that have depended on this particular style of shopping behavior. So far, much of the research has agreed that rural areas, including tourism-rich regions, are positioned to benefit from this trend.

Rural and tourism-rich counties are estimated to collect more local sales tax revenue than urban counties when controlling for factors like per-capita income, population, and percentage of the population that is unemployed.[12]

Again, this makes sense. The Supreme Court ruling and the Minnesota Department of Revenue’s efforts have made it so that only one type of purchaser will no longer be spending their tax dollars in these communities: residents outside the community who order something online and have the product shipped to their home. It’s likely that the consumer that is staying home and having goods delivered to their home made up a small percentage of the consumer pie for tourism-rich counties and economic centers.

Table 1: For tourism-rich and economic centers, there is only one way in which they lose out on local option sales tax (LOST) dollars: the consumer who doesn’t live there who orders online and has the product delivered to their home. Otherwise, all other consumers continue to pay the local-option sales tax (LOST).

|

|

Product ordered online & delivered to home |

Product delivered to store for pick-up |

Product purchased and picked up in store |

Product purchased at store, shipped to different community |

|

Resident of community |

LOST |

LOST |

LOST |

LOST |

|

Resident outside of community |

No LOST |

LOST |

LOST |

LOST |

Impact on commercial property tax revenues

Despite the optimistic story with sales tax revenues, though, there is another different but related concern: property taxes. One of the more visible changes that rural leaders are concerned about is the decreasing number of retail brick-and-mortar businesses in their communities—the empty storefronts on Main Street. In this case, what they see aligns with the data.

Figure 5 provides the change in the number of retail firms in each county group since 2004. The number of retail business establishments has fallen across the entire state since then, and research shows that this trend has been occurring since the 1990s. The most severe declines have occurred in the most rural areas of the state, which has lost nearly 25% of their retail businesses.

Figure 5: Although all types of counties in Minnesota have seen a decrease in the number of retail businesses, the most severe declines have taken place in our rural areas. Data: MN Department of Revenue – Minnesota Sales and Use Tax

Physical establishments pay property taxes, but although the decline appears discouraging for all areas, ample research points toward the growth of other industries that can make up for that loss. Figure 6 shows that, in urban areas, this is true. Other industries are seeing significant growth, which in turn is making up for the loss of retail properties.

Unfortunately, this hasn’t been the case in rural areas. This lack of growth in other industries has translated into an overall decline in businesses in these regions.

Figure 6: In our more urban areas, the growth in non-retail firms can make up for the declines in retail firms. That’s not the case in our rural areas of the state, leading to overall declines in the number of firms. Data: MN Department of Revenue – MN Sales and Use Tax

Because of this double whammy—a decline in the number of retail stores and a lack of growth in other industries—the apparent increase local leaders are seeing in the number of vacant commercial properties is real. Interestingly, this trend hasn’t translated into serious impacts on property tax revenues yet. Overall, while property taxes from retail properties may continue to shrink, other property types are keeping the total revenue pot afloat, partly because of the fact that commercial properties make up a relatively small share of property tax revenue in rural areas, but mostly because of the significant growth in the value of residential and ag and forest land properties. Since 2005, property tax revenues across Minnesota have nearly doubled, but the largest increases have been in our more rural regions (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Despite the decreasing number of retail firms throughout Minnesota, there has been little impact on total property taxes. Data: MN Department of Revenue – County Property Tax Data

Figure 8 shows the change in property taxes (size of bubble) for each property category as well as the proportion of total property taxes paid by each category (location on y-axis). It clearly shows that the more rural a county is, the higher the growth and proportion of total property taxes that come from ag land. Property tax revenue from commercial properties has experienced a bit of growth, but it also makes up a comparatively small share of total property taxes for rural counties. At the same time, residential properties are the inverse of ag and forest lands: the more urban a county is, the larger the share the residential class makes up of total property tax revenue while the share based on ag and forest land shrinks.

Figure 8: In rural areas of the state, the largest increase in property taxes has been in the ag and forest land classes, which also make up the largest percentage of total property taxes in these regions. As a county becomes more urban, residential, commercial and industrial become more prominent. Data: MN Department of Revenue – County Property Tax Data

Of course, every county is going to be a bit different, depending on the geographic, topographic and economic makeup of each county. Figure 9 provides the change in total net property taxes since 2005 for four counties that have economic centers within them: Beltrami (Bemidji), Douglas (Alexandria), Freeborn (Albert Lea), and Kandiyohi (Willmar). As the chart shows, growth in total property taxes are very similar despite their very different locations and economies.

Figure 9: These four counties all have economic centers located within them but each are located in different regions of the state. The change in total property taxes grows similarly despite their very different regions and economic makeup. Data: MN Department of Revenue – County Property Data

Even though the growth in property tax revenues are similar across these counties, the source of this growth can vary. Figure 10 provides the change in property taxes (size of bubble) paid by each property category as well as the proportion of total property taxes paid by each category (location on y-axis). The chart shows that some counties (such as the ones in lakes country) will likely rely more on residential properties, where values are increasing faster than other parts of rural Minnesota, as well as cabins and resorts. For other counties, the reliance may shift towards ag and forest lands where values are the highest, such as Kandiyohi and Freeborn.

Figure 10: The differences in region and economic activity in the county determines the diversity of property tax revenue sources. Tax revenues from commercial properties are between 10% and 20% of the total pie while also having similar growth from 2005. Data: MN Department of Revenue – County Property Tax Data

Conclusion: Things to keep an eye on

For further attention

The growth in online sales, however, will continue to have a significant influence on brick-and-mortar retailers. Although rural areas of the state that may have lacked retail options in the past will likely benefit from access to online shopping, the economic centers that rely on importing their taxes from out-of-community consumers and property taxes from commercial are somewhat exposed. As this trend continues, we recommend that the state monitors a couple of key issues:

- Property tax revenue sources: Although retail and commercial properties make up a relatively small percentage of the total property tax pie for rural areas, it’s likely to continue to shrink. The impacts may be minimal now, but if any of the other property tax sources propping up local government revenue decline, especially ag land values, rural areas could be in trouble. In addition, if reliance on one type of property becomes too onerous for property owners, there could be significant blowback from those who feel it’s unfair.

- Better categorize gross sales data: We can’t stress enough how well the Department of Revenue has worked to streamline sales tax information for businesses to charge and remit sales taxes and make sure the correct amount goes to the correct jurisdiction. Community leaders should feel at ease knowing this system is in place. As these trends continue, however, the DOR will need to monitor the impacts these shifts are having on local sales tax revenues. Knowing how shoppers in our communities purchase their products is important for rural economic development strategies. But although the Minnesota Department of Revenue gathers a lot of data, that information is not currently categorized in a way that is particularly useful for accurately estimating the proportion of sales taking place online, either from online out-of-state sellers or from an in-state retailer with a brick-and-mortar location. This isn’t the Department of Revenue’s fault as they are reliant on the information given to them by the firms remitting the sales tax information. Moving forward, however, it would be worth investing some dollars into the Department of Revenue to explore ways in which the data could be better organized and made more useful.

[1] Cavallo, “More Amazon Effects.”

[2] Hawkins and Eppright, “Evidence on Sales Tax Revenue Erosion in Florida From E-Commerce”; Agrawal and Wildasin, “Technology and Tax Systems”; Afonso, “The Impact of the Amazon Tax on Local Sales Tax Revenue in Urban and Rural Jurisdictions”; Agrawal and Fox, “Taxing Goods and Services in a Digital Era.”

[3] Walczak and Cammenga.

[4] Ball, “State Sales and Use Tax Nexus After South Dakota v. Wayfair.”

[5] MN Department of Revenue, “Sales Tax FAQs for Remote Sellers.”

[6] https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/guide/taxes-and-rates

[7] https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/guide/nontaxable-sales-8

[8] https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/2021-03/FS110.pdf

[9] https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/2021-08/FS164.pdf

[10] https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/2021-02/FS177.pdf

[11] https://www.revenue.state.mn.us/sites/default/files/2021-02/FS177.pdf

[12] Afonso, “The Impact of the Amazon Tax on Local Sales Tax Revenue in Urban and Rural Jurisdictions.”