With the pandemic on the wane and people ramping up their transitions back to full-time work, childcare will be right back where it was before the pandemic—under-resourced and hard to find, especially in rural areas. And it has a real impact on our economy.

By Marnie Werner, Vice President, Research & Operations

Here at the Center for Rural Policy & Development, we’ve been studying the childcare shortage in Minnesota for over five years now. To get ready for writing this post, I went back and looked through what I’ve written in the past, and the thing that struck me was how much things have not changed.

Well, I take that back. Things have changed in that the situation has gotten worse, especially in rural Minnesota. Between year-end 2000 and year-end 2019 (just before the pandemic), Minnesota had lost almost half of its family (in-home) childcare capacity. That’s 71,088 spaces statewide. The development of center childcare took up some of the slack: centers added 51,165 spaces. Notice something there, though? There was still a deficit of almost 20,000 spaces. During 2020, we had a net loss of another 3,000 spaces. In other words, we had almost 23,000 fewer childcare spaces at the end of 2020 than we did twenty years earlier.

And that’s a state average. If you break the numbers out by the Twin Cities seven-county area and the rest of the state, the Twin Cities lost around 2,700 spaces, while the rest of the state lost over 20,000 spaces.

I’m not saying anything that parents don’t already know. What hasn’t been as apparent, though—at least not until the spring of 2020—is the impact this childcare shortage can have on our economy. A year ago, almost to the day, I posted a piece looking at just that. I’m going to reuse some of it because it’s a little uncanny how much it sounds like I could have written it yesterday.

A lack of reliable child care was the single biggest problem for employees in America before the pandemic. Now, as parents head back to work, they will be looking for child care, whether it’s with their old provider or a new one, and that will drive up demand on an already stressed system.

An October 2020 article from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis lays out the economic impacts of not having enough child care. In their review of two surveys conducted just before the pandemic by the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of Montana and the Montana Department of Labor & Industry respectively, author Rob Grunewald found that “some child care-related work problems can directly affect household income in the near term, such as missing work (62 percent), changing from full-time to part-time work (15 percent) or quitting a job (12 percent).”

What was perhaps more troubling was that 26% of workers responding reported “declining to pursue further education or training” while 22% reported turning down a job offer, two moves that can affect a parent’s career trajectory, the article stated.

All in all, the studies reported the average Montana household with children under 6 losing $5,700 a year “due to missing work, switching from full-time work to part-time work, or turning down a job offer because of inadequate child care.”

Even two-parent households where one parent stays home with the children “lose an annual average of $2,960 due to child care problems.” Altogether, parents of young children in Montana “lose more than $145 million in wages because of inadequate child care,” while the federal and state governments lose $32 million a year in income tax receipts and businesses lose out on almost $55 million in revenue due to lost parental wages, lower worker productivity, higher turnover rates and a shrinking pool of qualified workers, all due to inadequate child care, the article stated. Low-income and American Indian households were affected even more, the studies found.

|

All families |

Low-income families |

High-income families |

Native American families |

White families |

|

|

Saying they were more likely to decline pursuing further education or training |

26% |

38% |

21% |

47% |

24% |

|

Turn down job offers |

22% |

36% |

12% |

37% |

22% |

|

Quit their jobs |

26% |

10% |

27% |

10% |

These studies from Montana were completed before the pandemic. During the pandemic, Grunewald and his Minneapolis Fed colleagues also found the impact of child care interruptions were falling disproportionately on women.

Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey, the authors showed that at the beginning of the pandemic (April 2020), nationwide “mothers and fathers of young children were, respectively, 1.7 and 1.4 percentage points more likely to report that home and/or family care responsibilities kept them out of the labor force than in November 2019.”

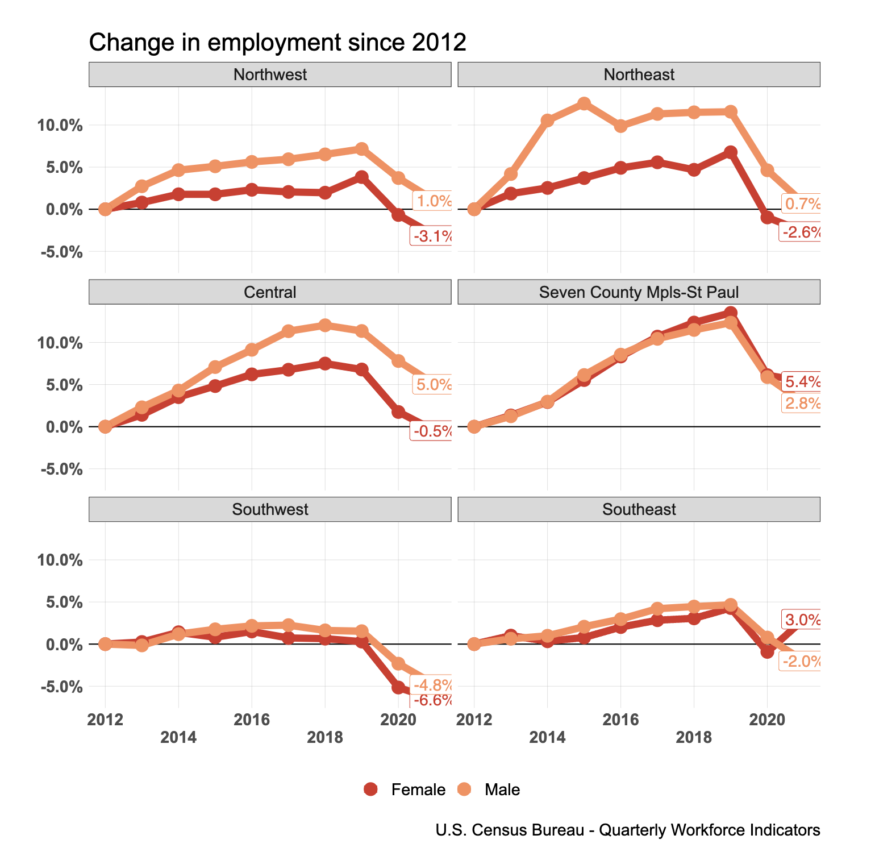

By November of 2020, though, the statistics showed that mothers of young children were 2.2 percentage points more likely than the year before to report that childcare responsibilities were keeping them out of the labor force. Our own analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau showed that by the end of 2021, women’s workforce participation had still not recovered to its 2012 levels except in the Twin Cities and in southeastern Minnesota. Meanwhile, fathers’ work participation was improving everywhere in the state, except in southwestern Minnesota.

Add something from that other Fed post on survey of providers?

Now that the pandemic seems to be winding down, it’s time to get back to what we were doing at the beginning of 2020: thinking about Greater Minnesota’s potential for growth and vitality. We still have that need for workers—that hasn’t gone away. Our economy might not be expanding quite like it was two years ago, but it can get back there—if we can find the workers. And with the interest in living in rural areas that blossomed during the pandemic, it’s just as important now as it was a year ago that we figure out how to support and grow our rural child care network. We’ll be looking at that more closely later this spring when we release our report on childcare initiatives being tried around the state. We’ll be patching things up and getting things on track again, and that’s going mean supporting and helping our providers do the same. The wellbeing of our communities depend on it.