A report in partnership with the Center for Rural Behavioral Health, Minnesota State University, Mankato.

As suicide rates race upward, rural residents struggle with a lack of services, information, and answers.

Marnie Werner, VP Research, Center for Rural Policy & Development &

Tracie Rutherford Self, Ph.D., Minnesota State University Mankato

February 2024

Click here for a printable pdf of this report.

Since about 2000, deaths by suicide have been rising at a steady and alarming rate. Every day, it seems, we hear that another person, usually a young person, has taken their own life. Something that was once a tragic rarity, suicide has become an almost daily occurrence that is frightening families, shaking communities, and challenging leaders on what to do and how to do it fast enough.

Suicide can be prevented and people contemplating suicide can get better, but both require intervention, information, and cooperation.

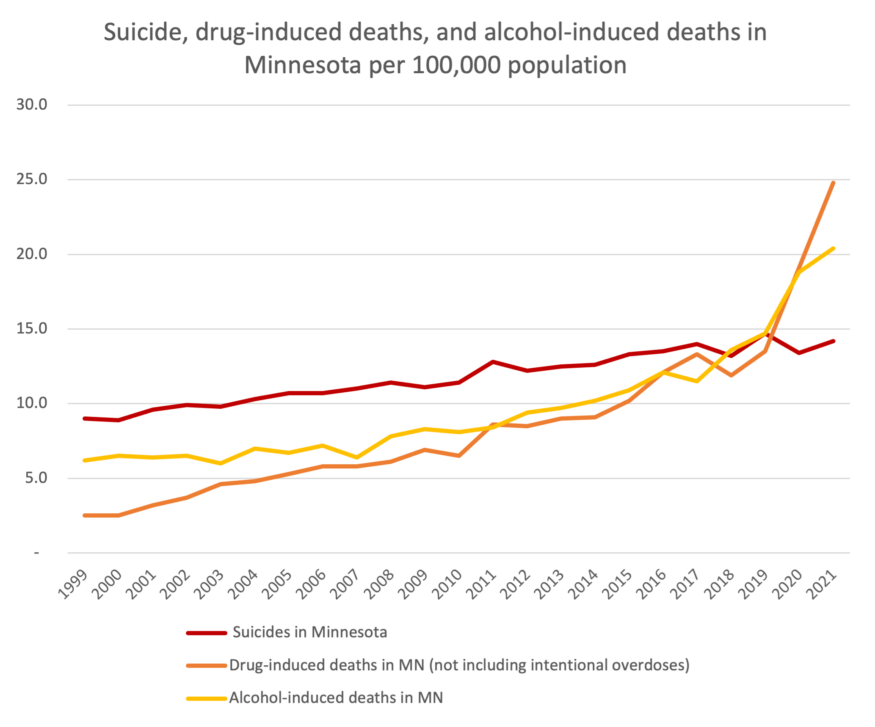

Mortality rates in the United States and in Minnesota were on a steady decline until about 2009, when the rate reversed. The cause, researchers found, was the growing number of “deaths of despair” (Case and Deaton, 2015). The terms “diseases of despair” and “deaths of despair” were coined in 2015 and are characterized by the increasing number of deaths from suicide and excessive drug and alcohol use. The increased rate in deaths of despair was first noticed in middle-age white (non-Hispanic) men, but since then, the rate has been increasing for other racial and ethnic groups as well.

Figure 1: Deaths of despair have been rising steadily in Minnesota since 1999, but drug- and alcohol-induced deaths took off during the pandemic. Data: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

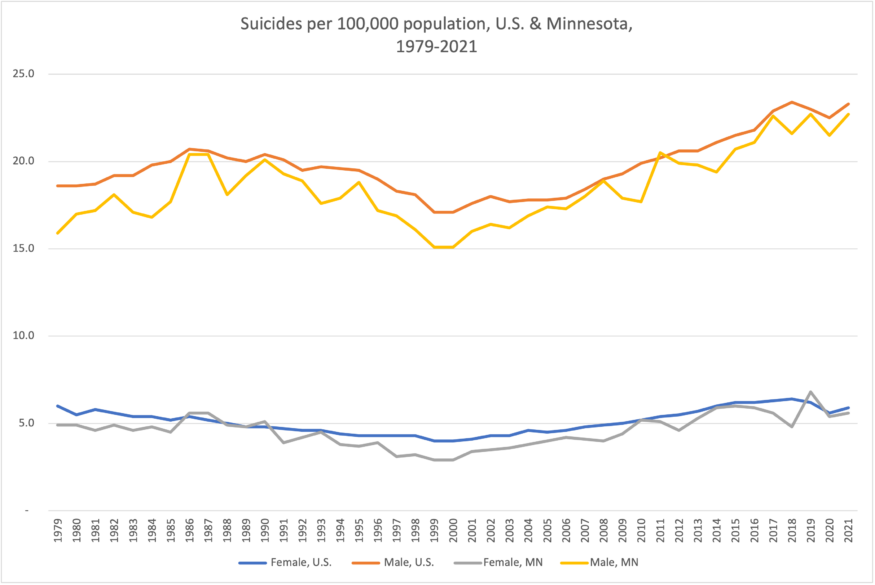

Figure 2: The increase in deaths by suicide since 2000 is especially noticeable among men, but also shows up for women. Data: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

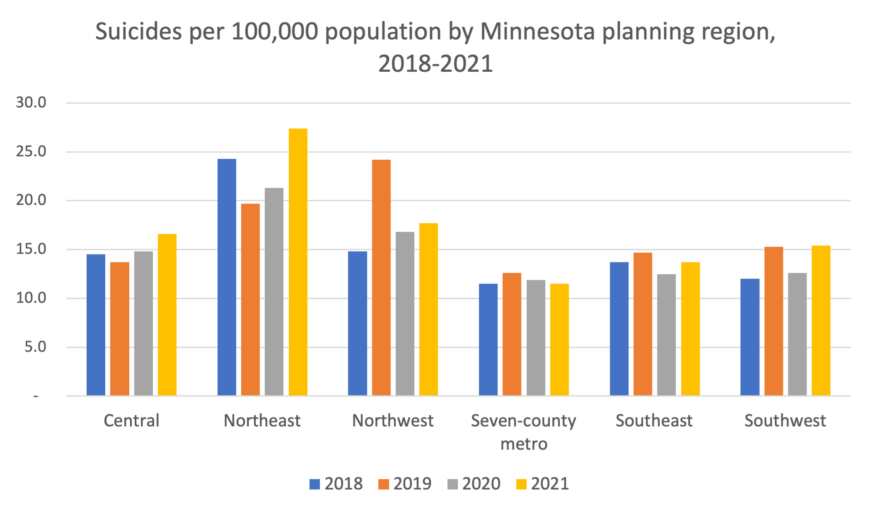

Figure 3: Suicide rates tend to be higher in rural areas, and Minnesota is no exception. Data: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

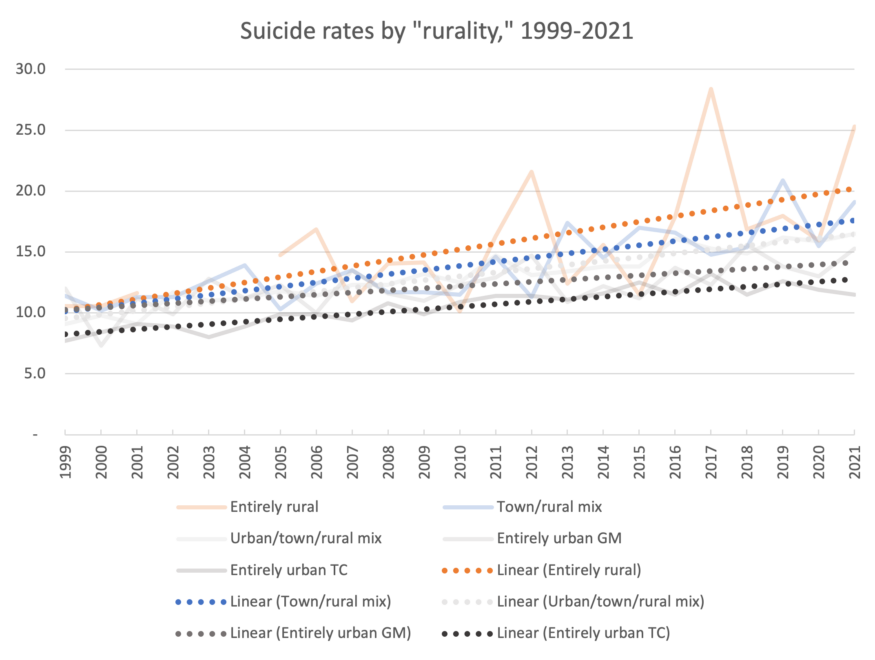

Suicide rates also tend to be higher in rural areas, including in Minnesota. As Figure 3 shows, suicide rates from 2018 to 2021 were highest in northeast and northwest Minnesota and lowest in the seven-county Twin Cities area. If we look at suicide rates by population density, the trendlines in Figure 4 show that suicide rates in our most rural counties are spiking higher and trending up faster than the more densely populated county groups. (For a map showing how we group Minnesota counties by “rurality,” visit our web site at ruralmn.org for a map and discussion on Rural-Urban Commuting Areas.)

Figure 4: Data since 2000 show that the more rural the area, the higher the suicide rate and the faster it is trending upward. Data: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

Where does the despair come from?

To better understand what’s happening, we need to look at what affects people’s mental health and outlook on life. All people are affected throughout their lives by what are called social determinants of health (SDOHs). These factors range from quality of family life in childhood to economic security to number of friends, and they can have a positive or negative effect on a person’s physical and mental health (State Suicide Prevention Plan, 2023). They have a way of compounding or piling up on a person throughout life: more negative social determinants of health can affect a person more negatively. However, positive SDOHs have a positive effect, counteracting the negative ones.

For example, parents fighting followed by divorce followed by a family move, which caused arguing between the parent and child can all work together to push a child into depression. Unless dealt with, these negative experiences simmer, affecting the adult’s outlook and mindset, potentially causing them to turn to alcohol and drugs for relief, and even suicide when things get bad enough.

In the case of suicide, it can seem like one particular bad experience is “the final straw” that results in suicide, but it is usually a series of problems or a cluster of problems that all happen at the same time and over time make it “impossible to pinpoint one specific event that led them to take their life” (Holland et al., 2017).

The Minnesota Department of Health’s Suicide Prevention unit and the Minnesota Suicide Prevention Task Force have identified a number of groups of particular concern in their State Suicide Prevention Plan. These groups show higher than average suicide rates:

- Youth age 10-24

- Middle-age males

- Black/African Americans

- Veterans

- People with disabilities

- LGBTQ+ communities

- Native Americans.

Why do rural areas have higher than average suicide rates?

Unfortunately, a number of barriers keep people in rural areas from getting the care they need:

Lack of access to mental healthcare. A shortage of mental health professionals equals a shortage of mental health services. Rural areas typically have fewer mental health professionals per capita compared to urban areas, resulting in longer wait times for appointments and limited availability of services. In a 2023 report from the Center for Rural Policy & Development (CRPD), we looked at how licensed mental health professionals are distributed around the state and found that 82% practiced in metropolitan regions. The data also showed that while the most densely populated counties of the state averaged 1 licensed professional for every 197 residents, the least populated counties averaged 1 licensed professional for every 741 residents, a striking difference.

This shortage of services has increased the distance people need to travel to reach a clinic or any other kind of mental health service and has resulted in weeks- or months-long waiting lists to see someone. People who are experiencing worsening mental health symptoms and can’t access services often end up in an emergency department, or worse, in the local jail.

Financial barriers. Limited financial resources and lower average incomes among rural residents may prevent people from affording mental health services, especially if they are not covered by insurance or if they have plans with high out-of-pocket costs. Rural areas also have more small businesses, which are more likely to not provide health insurance to their employees, making it necessary for a person to pay for mental health services out of pocket.

Medicare and Medicaid can be inconsistent in what they cover. Not every mental health service is covered by Medicare and Medicaid, and mental health service providers tend to be reimbursed at a lower amount than services for physical healthcare. Also, health insurance companies tend to use Medicare and Medicaid as a guide for setting their reimbursement rates.

More jobs/industries in rural areas involve physical/manual labor, which leads to more injury and chronic pain. Add to this less access to effective health care like physical therapy and we find more people turning to potentially addicting painkillers or suicide when the pain becomes intolerable.

Insufficient outreach and education. Lack of awareness and education about mental health issues and available services in rural communities may keep people from recognizing that they need help or knowing where to go for it.

Stigma and privacy concerns. Stigma surrounding mental illness in rural communities can deter people from seeking help. Local attitudes may view mental health issues as taboo or a sign of weakness, contributing to the reluctance to seek care. People living in small, close-knit communities may be concerned about confidentiality and privacy, leading them to avoid seeking care out of a fear of stigma or gossip.

More access to firearms. Gun ownership is higher in rural areas, making it easier for a person to access a firearm when they are most vulnerable to harming themselves.

We’ll discuss all these factors in more detail below, but before that, we also want to bring up two particularly hard-hit groups in rural areas: Native Americans and farmers.

Native Americans

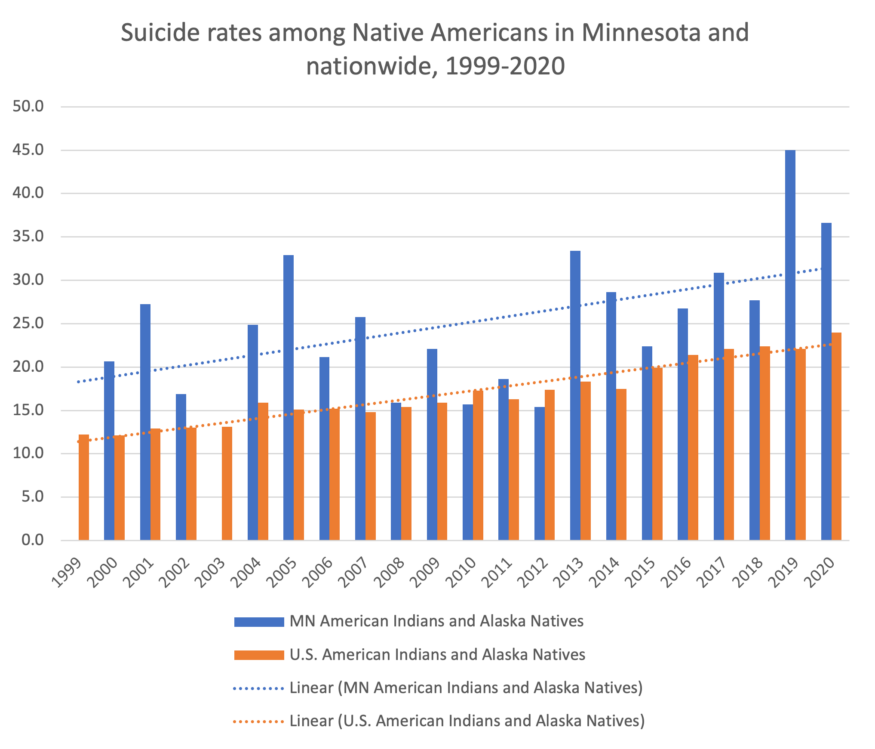

To protect people’s privacy, the CDC only reports deaths for specific regions and causes when there were 10 or more deaths (Charette and Goodman-Bacon, 2023), making it difficult to learn about deaths in racial and ethnic communities other than white, especially in rural areas. In Minnesota, however, there is enough data to show that the suicide rate among Native Americans in this state is much higher compared to Native Americans nationwide.

Figure 5: The suicide rate among Minnesota’s Native Americans is noticeably higher compared to Native Americans nationwide. (Data in 1999 and 2003 was either suppressed or deemed unreliable due to a low count.) Data: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

“In particular, suicides peak in the late teens and 20s—when people would otherwise be investing in themselves, starting careers, or forming families…” (Charette and Goodman-Bacon, 2023).

Economic opportunity may be one factor: “Native Americans and White Americans with similar economic circumstances had rates of distress that were statistically indistinguishable,” researchers in one study stated (Blanchflower and Feir, 2022).

Being a small and isolated population may be a factor as well. Chronic distress, that ongoing emotional burden that weighs on a person, “is lower among Native American people living in states with the largest Native American populations generally. There are positive payoffs to having similar neighbors.” (Blanchflower and Feir, 2022)

(Note: CRPD will be releasing an additional report later this year on access to mental health services for people of color in rural communities.)

Farmers

Before 2020, the suicide rate among farmers had become the focus of news stories and discussions among policymakers on what to do. The attention disappeared at the start of the pandemic, but the problem did not. Farmers, who make up only 1.9% of Minnesota’s population, continue to struggle with some unique issues:

- The burden of losing the farm, not carrying on the legacy, or both.

- Volatility of the markets and as such, their income.

- Older farmers: losing a spouse. Younger farmers: relationship problems and divorce.

In cases of divorce, the family business (the farm) could be at stake. - Chronic physical pain from a lifetime of hard work.

- Watching the farming community dwindle as people continue to leave.

Epidemiologist Erik Zabel at the Minnesota Department of Health is re-examining the records on suicides in the farming community to see if they may be undercounted. By looking at deaths ruled as suicides but not identified as farmers and comparing their addresses to property tax records, Zabel can determine if that person lived on a farm. He has been able to identify more people who died by suicide but were not counted as farmers, especially women and young people.

How is the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline being used in Minnesota?

An important tool for suicide prevention for years has been the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, which connects people in crisis or their loved ones via call, text, or chat with trained counselors who live in the state. In 2022, the original ten-digit number was changed to 988; the state of Minnesota began a soft rollout promoting the new 988 number due to capacity concerns over getting the regional centers up and running, said Emily Lindeman, suicide prevention coordinator with the Minnesota Department of Health. As the centers become fully operational, though, the plan is to roll out more targeted regional advertising around the state in 2024.

Looking at the 988 usage data paints an interesting picture but one that might be premature. It’s important to note that the data presented here is somewhat incomplete: First, unlike 911, 988 operators cannot see the caller’s location, and the caller doesn’t have to give their location to receive support. Second, calls are routed to 988 centers based on the area code and first three digits of the number the person is calling from. This means a Minnesota resident using a cell phone with an out-of-state number will be routed to a center in the state with that area code. It also means 988 data are not exact, Lindeman cautions. The data we have, however, can give us an indication of how much 988 is being used and where. Lindeman also noted that call and text volume has increased substantially, at more than 1,000 more contacts per month, possibly due in part to the growing use of texts to 988, which have increased by 500%, and chat is also available.

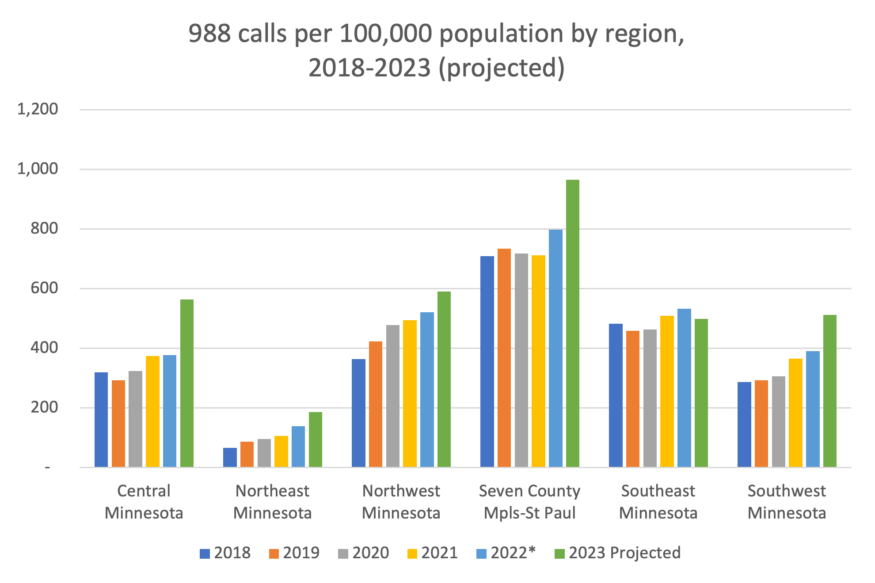

Figure 6: The rate of 988 calls has been growing since 2018 in most regions of Minnesota. Call rates are highest in the Twin Cities and lowest in Northeastern Minnesota, the region where suicide rates are highest. Data: Vibrant Emotional Health; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. *The number for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline switched to 988 in the middle of 2022. Only data through June 30, 2023, was available, so the remainder of 2023 was projected.

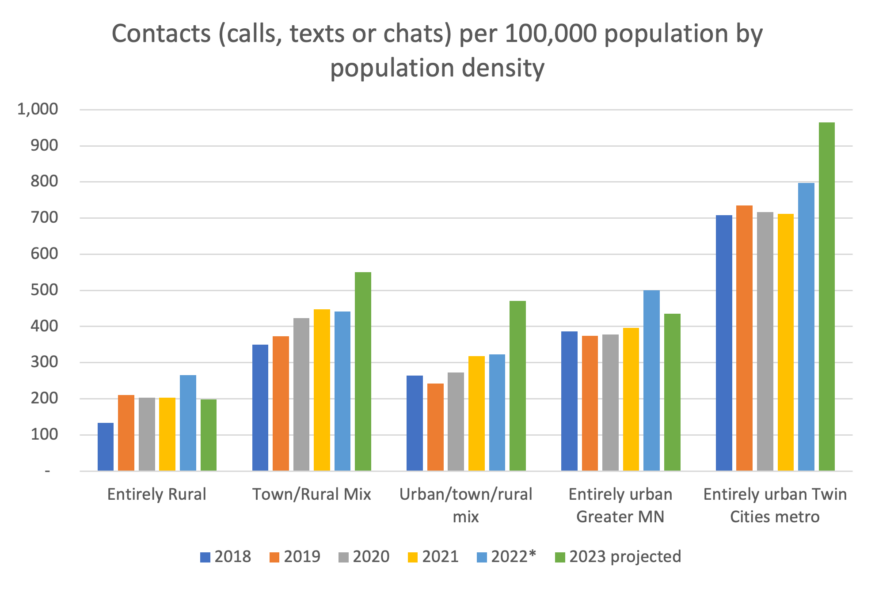

The concerning part is that the area with the lowest use of 988, according to the data, is Northeast Minnesota (Figure 6), which also has the highest rate of suicide of any region in the state (Figure 3). Conversely, the region with the highest rate of 988 use is the Twin Cities, which also has the lowest suicide rate among the regions. Figure 7 also shows how usage changes by rurality: the most rural counties have the lowest use rate. This may be a case of “you don’t know what you don’t know,” and that as 988 is rolled out and promoted across the state, people will become more aware of it and use rates will go up, and more importantly, suicide rates will go down. Lindeman shared that it’s also important to know that besides suicidal crises, 988 centers can also discuss substance use problems and mental health in general, making it an important resource for people seeking help.

Figure 7: Broken out by “rurality,” the rate of 988 usage has been the lowest in Minnesota’s most rural counties and highest in the Twin Cities metro area. Data: Vibrant Emotional Health; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. *As in the chart above, the number for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline switched to 988 in the middle of 2022. Only data through June 30, 2023, was available, so the remainder of 2023 was projected.

How do we move forward?

To get a better understanding of the unique challenges facing rural areas around mental health, especially in the case of a suicidal crisis, we conducted interviews with a number of mental health practitioners, educators, and others who serve rural clients. From these conversations three themes emerged, giving valuable—and sometimes surprising—insight into what causes the gap in rural areas between needing help and seeking help and what we can do to close that gap.

Theme 1: The need for rural cultural competence

While each interviewee acknowledged the need for more mental healthcare workers in rural areas, they also emphasized that it’s imperative that mental healthcare providers serving rural communities have rural cultural competence.

Defining rural cultural competence. In figuring out solutions to problems in rural areas, especially around mental health, it’s important to acknowledge that there is such a thing as rural culture and a need for rural cultural competence. Research supports the idea of a rural culture as a diversity issue (Slama, 2004) and that rural residents live with a set of characteristics different from those experienced by urban and suburban residents.

Cultural competence can be defined as the ability to acknowledge that we all see the world in different ways and have deeply held beliefs and opinions about how the world works based on our different circumstances and backgrounds. Beyond that, however, cultural competence also means we understand another person’s culture enough to be able to empathize with them and make them feel understood, valued, and not looked down upon.

While it’s challenging to come up with a consensus definition of “rural culture,” researchers have identified some of the common characteristics of rural culture that apply specifically to mental health: independence and self-reliance, isolation, being more likely to be economically insecure, a lack of trust regarding those outside their social network, the use of informal resources when seeking support, and a lack of anonymity—a “goldfish bowl effect”—that can increase a sense of stigma around mental health issues and a fear that community members will find out (Catron & Weiss, 1994; Heitkamp, Nielsen & Schroeder, 2019; Holmes and Levy, 2015; National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, 2017; USDA, 2018). There are strengths, too: valuing family, a strong work ethic, a strong sense of independence, and a connection to the land (Holmes and Levy, 2015).

Given the impact these characteristics can have on mental health, including suicide, it’s crucial that mental healthcare providers receive dedicated training and experience working with rural clients. Multicultural competence is being stressed in all behavioral health fields right now, and rightly so, but our interviewees indicated that training for mental health workers who may work in rural areas is incomplete without some form of rural cultural competence training.

Knowing someone understands you is crucial, especially to a person in crisis. Lindeman, a suicide prevention coordinator with the Minnesota Department of Health, tracks the data on 988 usage for the department. One thing she hears frequently is that people want to know that someone who cares is on the other end of the line, but also, “callers want to know they are talking to a fellow Minnesotan who lives there and understands their challenges, that these are local centers [and] as much as possible are run by Minnesotans.”

Rural communities are not all the same. In the context of this report, it is important to understand that rural communities in Minnesota are not homogenous. They are set in different geographical features and have unique economic drivers specific to Minnesota in the areas like farming, mining, forestry, and tourism. While there may be a specific cultural value system common to rural Minnesota, however, it must also be acknowledged that a farmer from southern Minnesota may have very different rural cultural values compared to a miner in northeastern Minnesota.

Even within the same communities, rural residents differ. For example, those who farm as an occupation may differ in attitudes and values from other community members who do not have a farming background. At the same time, many rural small-town residents have careers in the agricultural industry. They may have values and systems different from farming while still being a part of the overall rural culture.

“I think that’s huge,” says Monica McConkey, a rural mental health specialist in Detroit Lakes and one of the Minnesota Department of Agriculture’s two Farm Stress counselors. “I think in a state where there’s a lot of agriculture, it’s a necessity. We tend to be so metro-focused.”

Therefore, “rural” needs to be defined broadly. While farming is often discussed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data shows that the occupational sector with the highest rate of suicide is the sector that includes mining, far exceeding the rate of suicide in every other occupation. In fact, a 2021 CDC report noted that suicide rates in the Mining and Construction sector were as high as 72.0 per 100,000, while the Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting sector had a rate of 47.9 per 100,000, showing that farming communities in rural Minnesota can be quite different from communities on the Iron Range, which has an entirely different culture but is still rural.

Because of this dynamic, providers who are not familiar with the culture of the community they’re working in may have a harder time earning the trust of local residents, which helps no one. As such, courses around rural cultural competence that are adopted in rural-serving institutions, if not throughout the curriculum of behavioral health programs, should be embedded in an understanding of the people in those communities.

The distance issue. For Ericka LaMar, a mental healthcare provider with Essentia Health in Virginia, Minnesota, distance continues to be a major source of concern for residents of rural communities trying to access care and something mental health professionals and policymakers should take into account. LaMar sees people from as far away as International Falls, Grand Rapids, and Two Harbors. “That is a huge area. It’s not unusual for people to drive two and a half hours for care, because I am it.”

It’s especially a problem for children, who do not always respond positively to telehealth options and may need more direct, in-person therapies, such as play therapy. Molly Weinberger, a licensed professional clinical counselor in southern Minnesota, notes that the distances and difficulty in getting after-school appointments cause kids to miss school and messes with consistency in their therapy.

Even in cases where services come to the local area, distance causes inherent barriers. For example, for a mobile crisis unit coming from Mankato to another southern Minnesota town, “it’s probably an hour and a half, two hours to get there. . .. But if someone’s in crisis, later is not super helpful…. If a crisis situation is imminent, what we don’t want is someone waiting multiple hours to get assistance,” Weinberger said.

Farm competence. Mental health providers need to understand the unique stressors farmers and farm families face, along with their day-to-day working conditions, to better help their clients. When a therapist asked a dairy farmer what he thought about taking a week off, says Emily Krekelberg, a University of Minnesota Extension educator in farm safety & health, “I remember the dairy farmer told me, ‘I stayed for the rest of the appointment, but in that moment, the appointment was over.’”

Monica McConkey and Ted Matthews serve as the Minnesota Department of Agriculture’s two Rural Stress counselors, covering the entire state. They understand the stress of farming. “The isolation is still there,” McConkey said. “It’s the physical toll, it’s the weather, it’s the unpredictable markets, it’s the time commitment.”

Women in farming. One area requiring even further understanding is the role women play in the farming community and how their mental health is impacted. “They want to talk to another female that’s understanding agriculture,” McConkey said. “They could go to a female counselor anywhere, but there’s a disconnect. ‘You don’t understand my battle.’”

In Matthews’ opinion, the biggest change in farming over the last 5,000 years is the role of women on the farm, and that role has changed drastically. “What about her, about her stress? What about what’s going on with her?” Women on farms today are still raising the children, but they are also doing the books, helping with chores, working off the farm to help pay off debt or get health insurance. “As you well know, a lot more women attempt suicide than men.”

“They’re having kids, and they’re having to figure out how to balance that,” McConkey said, “and if they’re active on the farm— I mean I have lot of dairy women. The baby’s in the stroller in the aisle of the barn.”

Theme 2: Rural culture can create barriers to care

Rural culture in its own way can often stop people from seeking out needed mental health services. Three main points came out in our interviews: stigma, isolation, and relationship issues, all of which are consistent with current research as well (Holmes and Levey, 2015).

Stigma: Living in a goldfish bowl

Stigma around mental health and rural communities’ insular, self-contained nature creates an atmosphere that can make individuals reluctant to reach out for help, worried that if others find out, their social standing within their communities and social circles will be at risk.

“If you’re trying to seek behavioral healthcare,” says LaMar, “there’s this self-imposed barrier that, if you ask for help, you’re weak.”

Ted Matthews understood that from looking through his records while he worked for the Federal Emergency Management Agency. “Yeah, I looked in my records, and in one year, a total of zero farmers had ever called. So it became pretty obvious that farmers don’t call psychologists.”

“They’re independent,” says McConkey, “and so the thought of them seeking help, needing help— I mean these are the same people that there is no way they would be seen going to a food shelf… There’s just this strong, independent spirit that [says] ‘I don’t want to rely on somebody else, and I don’t want somebody else controlling me.’”

Rural residents often trust people they know, family members and friends who are members of their small towns and social groups (see the discussion on anchor members below), but they may not trust larger, unknown entities, including the government. Many rural residents hold a distrust of anything associated with the government, which can prevent people from doing something like contacting 988 out of fear that law enforcement will show up at their home for all to see.

Rural communities need take away the stigma, says Ted Matthews: “I think [people in] rural areas are far more worried about what other people think than in urban areas, and partly because in urban areas you don’t even know your neighbors. In rural areas you do… A factor that I see all the time is that word ‘yet.’ ‘It’s not bad enough yet.’”

LaMar does see things changing, however. “I’ve been up here for twenty years and living on the Iron Range and practicing on the Iron Range, and over the course of these last twenty years, I believe that there has been a very healthy shift away from the stigma of mental health.”

Isolation

Research has found that isolation also plays a key role in keeping rural residents from taking the appropriate steps to address their mental health concerns.

Isolation is a huge factor, said Ted Matthews. In his experience as a Farm Stress counselor, many farmers, as they get depressed, keep pulling away further and further, but almost no one notices. “That’s a big thing,” Matthews said. “There are farmers who look at a bad year and say, well, you have good years and you have bad years, and I’m good. Then you have farmers that, when you have a great year, they worry all year that they’re not going to, and then when they find out they had a good year, they start worrying about the next year.”

It’s not that one person is tougher or smarter, Matthews said. “We have to look at our own personality. How do I feel about things? How should I feel about things? Or boy, this farmer really handles that stress so well, and I don’t. What I need to do is say, ‘What can I do to be healthier, because this does bother me, and I shouldn’t be this way.’”

The danger of isolation cannot be overestimated. For LaMar, the challenge is that because rural people are isolated and they’re concerned about privacy, “they’re not talking to other people about what they’re going through. That leaves them at higher risk for completing suicide. Attempting and completing without intervention.”

“When we talk about building protective factors around these rural people, men in particular, that social isolation piece is huge,” says McConkey. Alcohol plays a big role, “because that is their social gathering, yet it’s not like it’s helping them as a protective factor. On some level it is, because they’re with these people day in and day out, sitting at the bar having drinks. But are [their friends] realizing when that person is in pain or hurting?”

Part of that isolation is a sense of “otherness” and a concern for those from outside the community that they may not be able to integrate into it. “There’s this really self-reliant virtue that runs among most of the folks that live up here,” says LaMar, “whether they’re fourth, fifth generation from here, or even transplants from twenty, thirty years ago. I would call it a closed community, meaning, if you’re not from here, it’s hard to break into the community.”

McConkey works with farm kids who feel very alone and isolated. “Their peers don’t understand their lifestyle, they can’t participate in all the things because they live too far [away], or they’ve got milk cows, they’re up at three in the morning helping with milking before they go to school. Just a lot.”

There is also still an isolating lack of awareness around prevention resources, especially as the state of Minnesota continues its rollout of 988 centers. McConkey, who practices in northern Minnesota and provides suicide prevention training there, is still shocked by how many people haven’t heard of 988.

“I always plug 988 wherever I’m at, in whatever community,” she said. “A lot of people don’t know about it.”

LaMar’s patients who have reached out to use 988 have had positive experiences.

“All of them have said that somebody picks up very quickly,” LaMar said. “I have two patients who actually regularly use the service and said that every time they’ve talked to somebody, the person has been really comforting.”

Telehealth is consistently put forward as a solution to the distance, worker shortage, and isolation problems, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. But while telehealth has opened doors for providing and receiving services, our interviewees have clients who still prefer in-person services, even when they have to cover great distances to access it, especially in a crisis setting.

“A lot of people don’t want to do telehealth,” says LaMar. “They want to sit in the room with a warm body.”

McConkey points out that broadband is still an issue in rural areas, too: “Broadband is huge. I know they’re working on it, but it just so exacerbates isolation when people can’t even log on.”

Relationship issues

Given issues with isolation and culture, it is not surprising to discover many rural residents face relationship issues as well. Relationships have a significant impact on a person’s well-being, whether for good or ill. One study found that relationship problems, particularly with parents, were the most common type of issue in the lives of at-risk youth who eventually took their own lives (Holland, et al., 2017).

Demands from typical occupations in rural communities, especially farming, often place stress on relationships. Says Matthews: “I don’t think it would surprise you at all to know that I do more marriage counseling right after harvest than any other time.”

“I have several young adult clients who are single, who have almost given up hope of finding a significant other because they never get off the farm to meet anybody,” McConkey said.

Letting down family members, especially parents, is another issue, especially in farming, when members of the family are relying on younger generations to take over. One client of McConkey’s doesn’t want to leave her aging parents to do the farm work themselves, but she is also having thoughts of suicide.

“That is a huge burden for a young person to carry,” McConkey said.

Access to firearms

Among the many factors contributing to a higher suicide rate in rural Minnesota, the largest one may be access to firearms. Although it is difficult to know exactly how many firearms there are in Minnesota—the data company Statista reported more than 129,000 registered firearms in the state in 2021 (Statista.com, 2021)—what is known is that for various reasons—hunting, protection, sports—gun ownership is more common in rural areas.

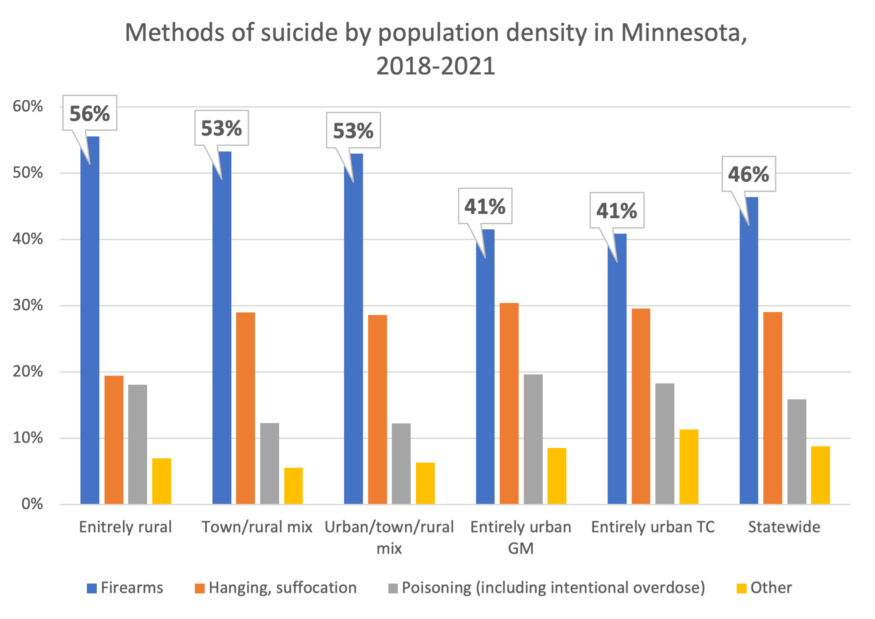

Figure 8 shows that in about half the suicides statewide between 2018 and 2021, the person used a gun, but those percentages are higher in rural areas and lower in more urban areas.

Figure 8: The use of firearms as a means for suicide is highest in rural areas, probably due to the higher rate of gun ownership. The chart shows the means of suicide between 2018 and 2021. Data: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

Regardless of what anyone thinks about guns, it is a fact that among the different methods people use to take their own lives, firearms are the most lethal. While poisoning using medication is the most common method used in attempting suicide, firearms result in more deaths. Taking one’s own life is usually done on the spur of the moment. Even if the person has been thinking about suicide and planning it for a long time, the act of taking action is often impulsive (Means Matter: Duration of Suicidal Crises, 2012). Therefore, if a person has a gun at hand, they are more likely to complete their suicide compared to a drug overdose, where there is often time to help the person.

Table 1: If firearms are taken out of the equation, suicide deaths drop dramatically. Suicide deaths per 100,000 population, with and without firearms, by RUCA, 2018-2021.

|

Means |

Entirely |

Town/rural |

Urban/town/ |

Entirely urban Greater MN |

Entirely urban Twin Cities |

Statewide |

|

With firearms |

19.0 |

17.7 |

15.9 |

14.4 |

11.9 |

13.9 |

|

Without firearms |

8.5 |

8.3 |

7.5 |

8.4 |

7.0 |

7.4 |

Taking firearms out of the equation makes a big difference (Table 1), but it must be done thoughtfully. Gun culture is a reality, McConkey said. “Part of it is like, ‘This is something I control, and this is a right that I have. This is like ingrained in me as self-protection. There’s a lot of mistrust of government organizations and agencies, and I’m not giving in to that.’”

Given the distrust of the government in rural communities, there is the danger that the state’s new “red flag” law could heighten tensions. Many myths and fears already circulate around seeking help. One big one is that as soon as a person is diagnosed with a mental illness, the counselor must notify law enforcement to take away their firearms. This is not true.

The new red flag law states that a person who believes someone poses a “significant” risk to themselves or others by possessing a firearm can apply for an extreme risk protection order to have that person’s firearms removed from their possession temporarily. The person making the request must prove to a judge in a court hearing that the gun owner is a “significant” risk to themselves or others. If the judge agrees, the gun owner can surrender their firearms voluntarily (no need for law enforcement to show up at the house), and the order is temporary.

Between doing nothing and law enforcement getting involved, however, there are other options, including strategies like Conversations Around Lethal Methods (CALM). CALM harnesses the power of friends and family by showing them how to talk to loved ones who may be suicidal about removing their guns in a way that shows caring and respect without escalating the situation. One example is this public service video that can be found on YouTube at liveonutah.org.

Theme 3: The path forward: What do we do now?

Despite how serious the suicide and mental health crisis appears, our interviewees still found reasons for optimism and offered steps that could be taken to help rural communities.

1. Recognizing the importance of anchor members of the community

Maybe because of the lack of providers or the issue of stigma or the amount of distrust of outsiders, many rural residents rely on informal resources like close friends and family for support, something echoed in the research (Holmes and Levy, 2015). Rural residents are more likely to rely on friends or neighbors for assistance than to seek outside help, particularly when it relates to mental health.

“The Iron Range in general is a very tight-knit, family-focused community,” LaMar said. What often happens is that somebody in the community, a friend or a family member, is worried about a friend or a family member. “Someone may say something that’s concerning,” said LaMar, “and the friend or family member convinces the person in distress to go to the emergency department. That’s usually how that goes down.”

“That’s one of the positives of not being anonymous in a rural community,” McConkey said. “We know what’s going on with everybody, but we can do more than gossip about it. We can go to them and say, ‘Hey, I’ve heard this. Are you okay?’”

While some may worry that the average resident doesn’t have the “proper training” or “wouldn’t know what to say” to help a loved one in crisis, it’s important to note that these friends and family members may be in the best position, due to their trusted relationship, to smooth the way for that struggling individual to take that first step toward reaching out for help. But the family members must be open to having conversations around mental health.

2. Instituting Integrated Behavioral Health

“I’m a jack of all trades because you have to be when you work mental health, rural mental health,” LaMar said.

Because of the general shortage of healthcare workers in rural areas, healthcare providers in general need to be well versed in multiple issues. In the case of mental health, the family doctor may be the first person to recognize someone is struggling with their mental health, or they may be the first professional that person approaches for help. For that reason, healthcare providers serving rural areas would need even more training in mental healthcare than their urban and suburban counterparts, especially when it comes to suicide.

Another option would be integrated behavioral health, having a mental health provider at the same clinic or nearby who can pop in quickly during a person’s regular doctor’s appointment. Ericka LaMar explains how this works: “The patient described having some difficulties with depression, so there would be what we called a warm handoff. I would come in, talk to them, do a quick screen, and talk to them about follow up if I felt like that was appropriate.”

Because the meeting is part of a primary care appointment, it helps increase access and makes behavioral health a part of a complete approach to health and wellness, LaMar says, plus, there’s anonymity because the person is already in the exam room. No one sees her with the client.

3. More providers versus the “right” providers

The National Health Service Corps’ mission is to place providers in health professional shortage areas, which are often in rural and underserved communities. This federal government program had more than 197 vacancies as of February 2024, and of those vacancies, almost 60% were for behavioral health professionals, illustrating the need for workers.

Is it enough, though, to simply place more providers in those communities?

While each provider we talked to believes there could be more providers in rural communities, they also noted that these providers must be well versed in understanding rural culture if they are going to help. As discussed earlier, without rural competence, counselors risk creating more harm to their clients than benefits simply through a lack of understanding. And given issues of trust as well as a reliance on community, it’s crucial to understand when placing behavioral health providers into rural communities that it will take time for them to acclimate to the culture and for rural residents to warm up to them. That makes it important that those placed in rural communities make solid connections with community leaders, who can then refer people.

For example, says Matthews, clergy are usually prominent members of the community and counsel many people, but they may not be trained in mental health. “They don’t have to be. What they have to do then is say, ‘Okay, if I can’t handle this, and I know something needs to be done, what can I do? Who do I refer them to?’ and so on. And giving them that relief to say I don’t have to be a therapist…. That becomes a pretty important factor.”

The following are just two examples of training programs that could help mental health providers and the general public learn more about mental health and suicide prevention.

Farm Stress Certification Program for Counselors. Minnesota is one of a handful of states that employs counselors with a specific farming background as a service to farmers. This program appears to have been very successful; however, there are only two counselors employed in this rural-specific program. There could be clients of other mental health providers who are not receiving rural-competent services. For example, a graduate student currently completing their hours toward an internship in Illinois mentioned recently that they were only just learning about the relationship between farmers and suicide.

Given that one quarter of Minnesota’s population lives in rural areas, it is important that the state’s colleges and universities consider adding a training course or continuing education certification on rural cultural competence for graduating students entering practice in rural communities.

Emily Krekelberg suggests the Farm Stress Certification Program for Counselors through Ohio State University Extension as one way to increase farm competence among graduating counselors. Minnesota institutions may wish to review this certification and provide coursework based on it for their mental health students. Farm-specific isn’t necessarily rural-specific, but it’s a start.

QPR training. An innovative project is QPR training for rural communities. A suicide prevention training, QPR (“question, persuade, refer”) can be offered to anyone interested in helping their community members, even though it isn’t necessarily ag- or rural-focused, Krekelberg said.

QPR training and the Farm Stress Certification program are prime opportunities for getting information to rural community members, which is important given the likelihood that they’ll engage with a struggling friend or family member before that person will seek help on their own. The effectiveness and long-term impact of these programs haven’t been studied, however, and therefore we would recommend more research that would help tailor QPR and other training programs to rural communities.

4. Normalizing conversations around mental health and yes, suicide

Given the tendency of rural residents to confide in family or friends first, it’s important for members of rural communities to talk about suicide in a way that makes it normal and okay to discuss. John Sommers-Flanagan, a prominent suicide researcher from the University of Montana, states in his many trainings on suicide that one of the goals is to “Normalize, normalize, normalize.”

Many of our interviewees have similar opinions.

“That’s why I constantly say, we’re all in this together,” Matthews said. People shouldn’t wait until they’re feeling seriously depressed to look for help. “We need to start as soon as you start feeling depressed. Why wouldn’t you want to do something? Why wouldn’t you want to be healthier? It starts from the beginning, not the end, right? I would say we want to start before they’re depressed.”

There is often a concern that talking about suicide may lead to “suicide contagion,” a phenomenon where a community has multiple suicides in a short span of time. But while suicide contagion is a real concern, the notion that discussing suicide will “put the thought” into the mind of a non-suicidal person is simply not true. Instead, talking about suicide in a healthy way helps relieve the stress of individuals who may already be thinking about it. In particular, young people who turn to suicide are often weighed down under feelings of loneliness, a lack of self-worth, and being a burden to others (Holland, et al., 2016). Being able to talk about suicide may actually decrease suicidal ideation and increase the likelihood that a person will seek help (Mayo, 2021).

Recommendations

In addition to the recommendations from our interviewees, we have a few more for state legislators and agencies based on our research.

Promoting 988

Support the Minnesota Department of Health in promoting 988 heavily in Greater Minnesota as soon as the capacity is there. Also, think about which state web sites people in crisis or their friends and family members might go to and display 988 prominently in those places. Google does this for seemingly any search that mentions “suicide.” The message is big and clear.

Develop an aggressive PSA campaign

Harness the power of anchor members of the community by developing an aggressive PSA campaign that teaches people how to talk about suicide. Working with one of the state’s many talented public relations firms, take a close look at what other states are doing—particularly Live On Utah with its many suicide prevention videos like this one—to use as templates for a PSA campaign in Minnesota. Anyone can be an anchor member in a rural community, which is why it is crucial that formal mental healthcare be partnered with informal mental healthcare. People can overcome their fear of saying something in case it’s the wrong thing when they get information and training.

Award grants where they’re needed most

Some communities in Greater Minnesota are seeing suicide outbreaks. Ensure that this is taken into consideration in the application process when determining where grants for community suicide prevention infrastructure should be awarded.

Help students stay where they intern

Support more student internships in rural areas. The way internships are currently done, they are a financial strain for both the student and the clinic where they’re interning, particularly in rural areas (Werner, et al., 2023). Because students are more likely to stay in a place where they’ve interned—they’ve lived there and have become familiar with the community—more internships in rural places can help relieve the mental health workforce shortage there.

The suicide epidemic caught many of us by surprise, so much so that there is no “getting ahead of the situation” any longer. Now we’re trying to catch up. Rural areas in particular face unique challenges that urban and suburban areas don’t, but fortunately there are also specific strategies government and the public can take to start getting the numbers going in the right direction—down.

Correction: The original version of this report mistakenly stated that mental health providers would be required to report firearms owned by clients deemed an extreme risk to themselves or others to law enforcement. This language was removed from the bill.

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to the individuals who participated in the interviews and otherwise assisted with the research for this report:

- Kelly Felton, Suicide Prevention Coordinator, Minnesota Department of Health

- Stefan Gingerich, Senior Epidemiologist, Injury and Violence Prevention Section, Minnesota Department of Health

- Emily Krekelberg, Extension Educator, Farm Safety & Health, University of Minnesota Extension

- Emily Lindeman, Suicide Prevention Coordinator, Minnesota Department of Health

- Ericka LaMar, Licensed Psychologist, Essentia Health, Virginia Clinic

- Ted Matthews, Director of Minnesota Rural Mental Health and Farm Stress counsellor for the Minnesota Department of Agriculture

- Monica McConkey, Licensed Professional Clinical Counselor, Minnesota Agricultural Mental Health Specialist

- Meg Moynihan, Ag Marketing & Development, Minnesota Department of Agriculture

- Molly Weinberger, Licensed Professional Clinical Counselor, Counseling Services of Southern Minnesota

- Erik Zabel, Epidemiologist, Minnesota Department of Health

References

Blanchflower, David, and Donn Feir. “Native Americans Consistently Report More Chronic Distress than Other Groups.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, January 20, 2022. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2022/native-americans-consistently-report-more-chronic-distress-than-other-groups.

Case, Anne, and Angus Deaton. “Rising Morbidity and Mortality in Midlife among White Non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st Century.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, no. 49 (December 8, 2015): 15078–83. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1518393112.

Catron, T., & Weiss, B. (1994). The Vanderbilt school-based counseling program: An interagency primary care model of mental health services. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 2(4), 247–253. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/106342669400200407

Charette, Elliot, and Andrew Goodman-Bacon. “‘Deaths of Despair’ and Economic Opportunity | Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, February 24, 2023. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2023/deaths-of-despair-and-economic-opportunity.

Health Resource & Services Administration. (2024). Health Workforce Connector. Retrieved from: https://connector.hrsa.gov/connector/

Heitkamp, T., Nielsen, S., & Schroeder, S. (2019). Promoting Positive Mental Health in Rural Schools. Mental Health Technology Transfer Center Network. https://mhttcnetwork.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/promoting-positive-mental-health-in-rural-schools.pdf

Holland, Kristin, Alana Vivolo-Kantor, Joseph Logan, and Ruth Leemis. “Antecedents of Suicide among Youth Aged 11-15: A Multistate Mixed Methods Analysis.” Journal of Youth & Adolescence 46, no. 7 (July 2017): 1598–1610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0610-3.

Holmes, C. & Levy M. (2015). Rural Culture Competence in Health Care White Paper. The University of Kansas School of Social Welfare, August. Retrieved from: https://reachhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/REACH-RCC-White-Paper-Final.pdf

Lazarus, F. (2023). Farm Stress Certification program Offered at OSU Extensions. Retrieved from: https://news.osu.edu/farm-stress-certification-program-offered-at-osu-extension/

Mayo Clinic Health System (2021). 8 common myths about suicide. Retrieved from: https://www.mayoclinichealthsystem.org/hometown-health/speaking-of-health/8-common-myths-about-suicide

“Means Matter: Duration of Suicidal Crises.” T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University, September 11, 2012. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/means-matter/means-matter/duration/.

Minnesota Office of the Revisor, Public Safety Bill (Chapter 52), August 1, 2023. https://www.revisor.mn.gov/laws/2023/0/Session+Law/Chapter/52/2023-08-07%2011:24:10+00:00/pdf.

National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services. (2017). Understanding the Impact of Suicide in Rural America: Policy Brief and Recommendations. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hrsa/advisory-committees/rural/publications/2017-impact-of-suicide.pdf

Slama, K. (2004). Rural Culture is a Diversity Issue. Minnesota Psychologist. Retrieved from: https://www.apa.org/practice/programs/rural/rural-culture.pdf

“State Suicide Prevention Plan.” MN Department of Health, February 3, 2023. https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/suicide/mnresponse/stateplan.html

Statista.com. “Number of Registered Weapons in the United States in 2021, by State,” October 2021. https://www.statista.com/statistics/215655/number-of-registered-weapons-in-the-us-by-state/.

Sussell A, Peterson C, Li J, Miniño A, Scott KA, Stone DM. Suicide Rates by Industry and Occupation — National Vital Statistics System, United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:1346–1350. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7250a2.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2018). Rural Poverty and Well-Being. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being/

Werner, Marnie, Thad Shunkweiler, and Tracie Rutherford Self. “Identifying Bottlenecks and Roadblocks in the Rural Mental Health Career Pipeline | Center for Rural Policy and Development.” Center for Rural Policy & Development, February 14, 2023. https://www.ruralmn.org/identifying-bottlenecks-and-roadblocks-in-the-rural-mental-health-career-pipeline/.