April 2022

By Kelly Asche, Research Associate

For a printable version of this report, click here.

Ambulance services save lives every day, but a report released by the Office of the Legislative Auditor in February of 2022 raises serious concerns about the way ambulance services in Minnesota are regulated, their future viability, and the operations of the Emergency Medical Services Regulatory Board, which oversees ambulance services in the state.[1] The report uncovered problems, in some cases going back decades, and it will hopefully jump-start some deep and serious discussions about the future of emergency medical services in Minnesota.

The problems the Legislative Auditor’s report discussed revolved largely around regulation, management, and sustainability. But while this report necessarily brings these issues to light, the auditors looked at the issues largely from a statewide perspective, an angle that can hide those issues unique to rural communities.

This report will take a closer look at those specifically rural issues. To do so, we analyzed survey data from the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) and conducted our own interviews with EMS officials around the state to examine more closely what makes these issues unique and how they can be addressed.

Through this lens, one key theme emerges: the future of our rural EMS agencies will not be ensured through increased funding alone. Having support systems for rural EMS to hire professionally trained managers, creating incentives for agencies to collaborate and consolidate, and creating policies that are flexible to match the nuance among issues within rural EMS will increase the likelihood that they can take the next step forward.

From transportation service to health care provider: Bringing rural EMS into the future

Minnesota’s Office of the Legislative Auditor conducts regular audits, or evaluations, of various state agencies and organizations that receive state funding. The result of these investigations is an in-depth report laying out in detail the problems the agency may be facing, their causes, and possible solutions.

For our report, we’ll address only two of the three main issues the OLA report brought up: sustainability and management. The regulatory issues uncovered by the Legislative Auditor are for the most part between the Emergency Medical Services Regulatory Board and the state legislature and aren’t affected much by whether an agency is in rural Minnesota or the Twin Cities.

However, the other two issues, sustainability and management, are greatly affected by location, and this is where we’ll start.

Some background

There are two facts of rural Minnesota that affect ambulance service: large geographic areas and small populations. These two facts affect everything to do with operating an ambulance service, from response time to revenue generation to workforce recruitment and retention.

The Minnesota Department of Health’s 2016 Rural EMS Sustainability Survey was developed and implemented in partnership with the Minnesota Emergency Medical Services Regulatory Board and the Minnesota Ambulance Association and was sent to 230 agencies—essentially every EMS agency outside of the Twin Cities Metro EMS Region, plus three Metro agencies that serve primarily rural populations. It achieved an outstanding 81% response rate.

At the time, results were presented in the aggregate, meaning all responses were lumped together, which can sometimes hide specific differences between small and large EMS agencies. What we found from splitting MDH’s survey data by various variables such as population size served and whether there was a formally trained manager, and our own interviews with EMS officials, is that when it comes to revenue generation and workforce recruitment and retention, the current financial and organizational structure that ambulance systems operate within can in fact negatively warp an agency’s ability to generate revenue and its ability to recruit and retain workers, whether paid or volunteer, depending on the density or sparsity of the population in that agency’s service area.

Emergency medical services (EMS) cover a wide field of services and personnel, but for this report, we’ll be focusing on just ambulance services.

Ambulance services began as a wartime necessity to transport and treat injured soldiers, but modern EMS services began in the 1960s. For a little over a decade the federal government made significant investments in EMS.

Unfortunately, since the late 1970s, federal support has dwindled. The federal government today provides grants to purchase equipment but not for initiatives that would lead to overhauls in how EMS functions. Therefore, while EMS today is a central component in modern health care, and despite significant advances in technology, equipment, training, and triage protocols, EMS agencies are still treated more like transportation services than healthcare providers. For example, there are still cases where an EMS team will not be reimbursed for showing up to a scene, even if they provide medical services, unless they also transport the patient.[2]

Even ideas for how to transform EMS services are not new. In 1997, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) issued a report, “Agenda for the Future,” that introduced a plan to integrate EMS into the healthcare system.[3] That was twenty-five years ago.

EMS professionals agree that the EMS field needs a significant evolution—away from being just an emergency response/transportation unit to being fully integrated into the healthcare provider field. This sort of shift will require a significant investment in equipment, staffing, coordination, and management, and that will require an intentional transformation in how EMS agencies are funded.

Revenue and sustainability

EMS in general is not funded as if it were an essential service. Unlike fire departments and law enforcement, which have more stable sources of income like property taxes to sustain their operations, most EMS agencies, especially rural ones, rely on a mix of funding sources that has evolved over the years into a complicated combo of billing for some services but not others, local subsidies, community fundraising, and grants. Yet like fire departments and law enforcement, EMS must be ready 24 hours a day.

The challenges facing rural EMS agencies range from recruitment and retention to the ability to upgrade equipment to disparities in the level of service they can provide, longer travel times from emergencies to hospital care, and integrating into the healthcare regional coordination continuum.[4] All of these are either impacted by or have an impact on an agency’s ability to raise operating revenue.

The factor with the most influence on how much revenue an agency can access is call volume. It’s a logical assumption: an agency with 1,000 calls a week needs more funding to operate than one that receives five calls a week.

However, because of the lack of economies of scale at work in rural areas (i.e., the lack of call volume), the system that can work for urban agencies—funding based on call volume—does not necessarily work for rural ones. First of all, the overhead needed to operate an agency exists regardless of the service area’s population. Overhead involves the building, utilities, the basic equipment, and other costs associated with operating and being ready all hours of the day.

Second, sparsely populated rural areas have characteristics that increase costs:

- Rural areas have a higher percentage of population that is older, poorer, unhealthier, and on fixed incomes.

- The percentage of households on insurance plans with high deductibles is increasing, which means a greater reliance on an individual’s ability to pay rather than the health insurance company’s.

- Older and poorer populations mean more clients on Medicare and Medicaid, whose fee schedules don’t reimburse for the full cost of EMS services provided.[5]

- The lower reimbursements from Medicare and Medicaid influences what insurance companies will pay to reimburse agencies for service.[6]

- The persistent philosophy that EMS is a transportation service rather than a skilled health care service.

The Minnesota legislature has been actively trying to find creative ways to allow agencies to support themselves. Counties can use property taxes to raise funds to support EMS agencies (and fire departments), and in 2021, the legislature increased the maximum allowed for those levies, since the original cap was thought to be so low that it wasn’t worth an EMS agency’s time to even pursue.

But although a special taxing district helps EMS shift away from the current broken business model toward a more distributive one, at the time of this writing no agencies had yet taken this option. Our interviews with EMS officials revealed that even with the higher cap, trying to “sell” the new property tax is challenging:

- Lack of support among county commissioners. County commissioners are already wary about adding another tax on property owners. As one agency manager said, “we are approaching this idea very carefully. So much is already pushed on the counties to pay for, and commissioners feel a need to protect property owners.”

- The property tax system does not make it easy to establish a tax on homeowners in rural areas. For example, one agency in southern Minnesota is exploring ways to tax homeowners instead of land. Ag land dominates tax bases in most of southern and southwestern Minnesota, which means that a property tax applied to land would result in a few landowners paying the bulk of the levy. The same issue prevented school districts from passing levy referendums for decades, and the results would likely be the same for any EMS referendum that was not carefully crafted.

Although these types of solutions are welcome, it’s also clear that these solutions will require someone on the ground to implement them. Full-time, professionally trained managers are becoming increasingly necessary to manage not only these types of funding solutions, but also the entire gamut of challenges and issues that rural EMS faces.

Professional management and sustainability

Despite the many ideas, strategies, policies, support systems, and plans produced to help address these issues, many of the solutions typically involve finding ways to increase revenues.[7] But even if federal and state policy fully addressed the financial side of EMS, the lack of formal staffing and management, it turns out, are also key barriers to rural EMS sustainability.

In 2016, 54% of EMS agencies outside of the seven-county metro had a manager with formal leadership or management training.[8] However, that percentage decreases significantly as the size of the population served by an agency decreases. Figure 1 shows that nearly 100% of agencies that serve a population 15,000 or greater have formally trained managers, but only 38% of agencies that serve a population of less than 2,500 can say the same.

Figure 1: The percentage of agencies with a manager that has formal leadership or management training declines significantly as the size of the population served decreases. Data: MN Department of Health – 2016 Rural EMS Sustainability Survey

A formally trained manager makes a difference. According to Ann Jensen, EMS Southwest Regional Program, EMS agencies are “businesses and non-profits in the health field that require significant understanding of the issues. The field of EMS has changed significantly over the last 10 years and the expectations are increasing.” Today’s EMS agency needs a manager who “understands license and training requirements, can navigate the philanthropic and payment ecosystem, can write grants, can appropriately deal with personnel issues while also have experience providing and integrating into health care services.”

Even if revenue for agencies increases, it won’t necessarily solve all their issues. A properly trained manager can be key to the success of a program.

For example, overcoming the issue of staff and volunteer recruitment will require a formal strategy involving various programs and incentives:[9][10]

-

- Identifying potential recruits by utilizing personal connections, visiting high schools, and holding open houses.

- An integrated approach to training, such as collaborating with health care providers.

- Creating a dedicated team within the agency to focus on recruitment and retention activities.

- Reducing barriers caused by the costs of training.

- Raising the visibility of the agency in the community.

- Offering incentives to employers who allow their employees to respond to calls during work hours.

- Investing in pay and benefits.

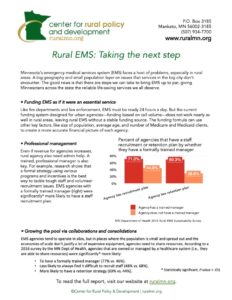

Without a dedicated manager with the training and resources to develop and implement this kind of formal strategic plan, these plans typically don’t get created, and breaking down the data between agencies with and without a formally trained manager backs this idea up. Figure 2 shows that agencies with a formally trained manager were significantly[11] more likely to have developed a staff/volunteer recruitment plan (71% vs. 45%) and a retention plan (70% vs. 29%) and were significantly less likely to consider recruitment to always be a challenge (52% vs. 75%).

Figure 2: An agency’s response to whether they are prepared for staff recruitment and retention and whether recruitment is challenging is related to whether they have a formally trained manager. Data: MN Department of Health – 2016 Rural EMS Sustainability Survey

Growing the pool via collaboration and consolidations

As part of the OLA report, researchers surveyed ambulance service directors statewide. Of the 186 who responded, 54 directors—29%—indicated that they were concerned or even very concerned over the future of their agencies, a number the OLA found concerning as well.[12]

In addition, agencies tend to operate in silos without the ability to share resources like equipment or even volunteers. Through our interviews with rural EMS agencies, there is growing agreement that pooling and sharing resources is a necessary step in rural EMS, and the way forward will likely include a mixture of collaboration, consolidation, and regionalization of our smallest agencies.

Minnesota is already divided into eight EMSRB program regions, which helps encourage collaboration between the state and the agencies, a level of coordination many states still don’t have for their rural EMS services. That’s where coordination stops, however.

In rural Minnesota, “consolidation” is a bad word. After decades of school district consolidations that left hundreds of small towns feeling the heart of their community had been ripped out along with their school, rural residents are understandably quite leery of anything involving the term “consolidation.”

In the case of EMS agencies, however, different types of relationships, including consolidations, across service areas are necessary to keep many of the state’s 250 EMS agencies functional going forward.

The benefits of increasing the pool

The first step would be to leverage the current framework (the eight EMSRB program regions along with the primary service areas) so that agencies don’t operate in silos and are instead able to share resources. While there has been some discussion around the franchise model that currently allows a single ambulance service to serve an area so that EMS agencies don’t have to fear competition, it’s important to recognize that agencies are still competing for resources such as grants and workforce. Small, rural EMS agencies that don’t have dedicated staff to write grants, develop recruitment and retention plans, and take care of the day-to-day business tasks are often at a disadvantage.

The primary benefit of developing relationships across service areas among EMS agencies has to do with economies of scale. The sunk costs of being ready 24 hours a day while only earning revenues from low call volumes is an economies of scale issue, ut so is trying to recruit workers and volunteers from a small pool of people. One benefit of collaboration, consolidation, and regionalization is a larger pool to draw on for potential workers.

Over the last ten years, CentraCare, one of the state’s major health care providers, provides an example of how economies of scale improve for agencies with both low and high call volumes. CentraCare currently manages and operates six primary service areas:

- Monticello/Big Lake/Becker

- Long Prairie/Todd County

- Paynesville

- Willmar

- Benson

- Redwood Falls

In the aggregate, the total annual call volume is about 13,000, but individually they range from 400 calls to 4,600.

According to Gordon Vosberg, Senior Director of EMS for CentraCare, operating multiple agencies under one roof allows them to shift and share resources to help alleviate the typical challenges that rural EMS agencies face.

“We put everything together and do not operate each one as silos,” says Vosberg. “Trainings, rigs, staffing, budgets, and all resources are shared. This also means we can shift resources from one service area to another if demand is needed.”

CentraCare’s system also gives areas served by small agencies access to more advanced care. For example, providing full-time advanced life support (ALS) at all their EMS stations isn’t feasible, but they are able to provide part-time advanced life support by providing their community paramedics with advanced life support equipment, which allows them to respond to EMS calls while out making patient visits in private homes. Having someone with ALS certification and being able to purchase the necessary equipment is not feasible for an agency with a low call volume. Pooling together means having access to at least part-time ALS.

Survey results.

In addition to anecdotal evidence, MDH’s survey data also indicate that agencies able to share resources with other agencies or healthcare institutions can alleviate the severity of issues a single rural EMS agency faces.

Although the survey didn’t ask if an agency was consolidated with another EMS agency, it did ask whether the agency was managed, owned, or had a relationship with a corporate healthcare system. This is an imperfect proxy for resource pooling, collaboration, and consolidations, but it’s a good assumption that being managed or owned by a corporate healthcare system indicates some ability to share and/or shift around resources, either with other EMS agencies operated by the healthcare system or within the healthcare system itself.

The survey results supported that assumption. While only 27% of respondents said their agency was owned, operated, or had a formal relationship with a corporate healthcare system, those that did responded to questions very differently compared to the others.

Importantly, agencies that were owned or managed by a healthcare system were significantly[13] more likely to have a formally trained manager (77% vs. 46%), significantly less likely to always find it difficult to recruit staff (48% vs. 68%), and significantly more likely to have a retention strategy (69% vs. 44%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Agencies that are owned, managed, or have a relationship with a healthcare system were more likely to have trained managers, have less trouble recruiting, and to have a staff retention strategy. Data: MN Department of Health – 2016 Rural EMS Sustainability survey

Perhaps most important, EMS agencies that were owned, managed, or had a relationship with a corporate health system were significantly[14] more likely to offer advanced life support compared to other agencies (58% vs. 16%, Figure 3).

This doesn’t mean that all EMS agencies should be owned or managed by a healthcare system. In fact, such an arrangement wouldn’t work for many EMS agencies across rural Minnesota simply because there are no large healthcare systems in their regions.

Rather, the data indicate that increasing the call volume (either through consolidation of EMS agencies or relationships with other healthcare providers) and the pool of resources (staff, equipment, management, etc.) can significantly increase the sustainability of an individual agency and increase their capacity to provide higher-level services.

Given the positive correlation between collaboration and sustainability, why aren’t more rural EMS providers rushing to do this? When asked this question in our interviews, every EMS agency responded by saying “community pride.” To residents of large communities, where an individual is far less likely to have any direct, personal connection with an EMS service or the people who provide the services, this may sound silly, but in small towns, the local EMS agency is a close and integral part of the community. Nearly all of these ambulance services were formed by people in the community and have long-time historical ties there. The ambulance carries the town or regional name on its side, and the staff have local and personal connections: they are friends, parents, siblings, neighbors. Staff are present and provide their services during high school sporting events, while people wear jackets with the EMS agency’s name embroidered on them. Many agencies are owned by the city or are part of the local fire department. There’s a lot to untangle – culturally, structurally, and economically – and it can seem very daunting.

To move forward, these conversations must happen locally and without force. Incentives could be offered to rural agencies to pursue conversations, along with technical and consultation support to help facilitate these conversations in a healthy, constructive manner. In addition, because each rural EMS agency faces unique situations serving their unique region, what a “consolidation” looks like needs to be flexible enough to allow workers to deliver services for their unique areas within the larger region. For example, some agencies have formed consortiums that allow them to share a medical director. This type of collaboration can be used to hire a highly trained manager to oversee multiple agencies. Another example would be to create incentives and supply technical support to help multiple agencies form a joint powers agreement.

If Stevens County EMS, for example, were a part of a larger consortium of surrounding agencies, says Josh Fischer, CFO and general manager of Stevens County EMS, a privately owned agency, “This type of consortium could allow us to share resources and pool together to be able to, for example, improve pay for EMTs and paramedics.”

A nuanced approach for transforming EMS

As Minnesota begins to take a comprehensive look at EMS, data becomes more important than ever, simply because each agency has unique needs that are determined by its unique set of demographic, economic, cultural, and structural variables. The differences aren’t just between the Twin Cities and the rest of the state: the differences even within rural Minnesota are important. Therefore, any policies, including support systems and performance standards, must be flexible enough to account for these circumstances.

An example is the issue of workforce and volunteer recruitment and retention. Rural EMS relies on volunteers to function. Figure 4 shows that, unsurprisingly, the percentage of agencies that pay their workers increases dramatically with population size, indicating that the smaller the population of the organization’s service area, the more dependent it is on volunteers.

Figure 4: The percentage of EMS agencies outside of the seven-county metro that pay their staff an hourly wage or salary increases significantly as the population of the service region increases. (Data: MN Department of Health – 2016 Rural EMS Sustainability Survey

This reliance on volunteers to staff rural EMS agencies is becoming an increasingly serious problem, for many reasons—the complexity of their duties is increasing, there is more turnover among volunteers, and it’s harder to fill the staffing schedule. In MDH’s survey, 51% of respondents said that staffing the schedule was a challenge, 63% said it was difficult to recruit new staff, and 94% responded that it was sometimes or always a challenge to retain staff.[15]

These statistics might lead to the conclusion that the smallest and most rural EMS agencies would have the most trouble recruiting and retaining workforce, but that’s not the case. In fact, the agencies with the most recruitment and retention challenges are those where call volume is too low to generate enough revenue to compensate staff sufficiently but also high enough to cause burnout among volunteers. Figure 5 shows that while a majority of EMS agencies serving a population of less than 10,000 say it’s difficult to recruit volunteers and staff, the largest percentage, over 77%, are among agencies serving between 2,500 and 4,999[16].

Figure 5: Although a majority of rural agencies say that staff recruitment is a challenge, the largest percentage is among agencies serving 2,500 to 4,999. Data: MN Department of Health – 2016 Rural EMS Sustainability Survey

This subtle distinction also shows up in the questions identifying the various barriers to staff recruitment in the survey. The results show that although agencies that serve lower populations (10,000 or less) are experiencing more of the barriers to recruiting staff and volunteers compared to agencies serving larger populations (10,000 or more), within that 10,000-or-less group, agencies serving “mid-size” populations (between 2,500 and 10,000) appear to be affected even more than the smallest agencies (less than 2,500, Figure 6).[17]

Figure 6: The recruitment barriers are more severe for agencies that have a call volume high enough to burnout volunteers, but not high enough to pay staff. Data: MN Department of Health – 2016 Rural EMS Sustainability Survey

What this data implies is that there is a level at which increasing call volumes strain volunteers enough to make them feel the time commitment is too great: they are stretched too thin, either because of competing time commitments or their employers feel they are leaving work too often. Yet the call volumes aren’t high enough to generate the revenue needed to compensate them at a level that they feel is commensurate to the workload—or to make it feasible to hire more staff.

On the flip side, agencies that serve our smallest population sizes don’t feel that inadequate pay is a significant barrier to volunteer and staff recruitment. It’s likely that the call volumes aren’t high enough to make volunteer burnout a major issue.

Another example of the nuanced way in which rural EMS may differ among each other is the amount of time needed for training. Call volumes at our smallest EMS agencies may be low enough that the time required for volunteering doesn’t feel like as much of a burden (Figure 7) but the amount of time required for training might.[18]

Figure 7: The percentage of agencies that say the time required for training staff is a barrier to staff recruitment is highest among our agencies serving the smallest populations. Data: MN Department of Health – 2016 Rural EMS Sustainability survey

So, what does this have to do with changing policy? It’s the failure to recognize and address these subtle differences that has allowed these challenges for rural EMS agencies to develop, and therefore, policies or rules cannot rely on just simple metrics like population served. In the example above, agencies serving slightly larger populations may need more support for staff and volunteer compensation to help with retention, while smaller agencies may be all right with a volunteer staff but lower training requirements.

Office of Legislative Auditor: Recommendations with a rural perspective

In the Office of the Legislative Auditor’s 2022 report, “Emergency Ambulance Services,” six primary recommendations are established for the legislature and the EMSRB Board to consider in addressing the issues found in their evaluation.[19]

- The Legislature should retain primary service areas for ambulance services, but it should restructure how they are created, modified, and overseen.

- The Legislature should adopt more stringent statutory requirements for renewal of ambulance service licenses.

- The Legislature should direct EMSRB to develop and enforce performance standards for ambulance services.

- The Legislature should explore options for improving ambulance service sustainability in Minnesota, potentially through pilot programs.

- The EMSRB board should improve its oversight of the executive director and ensure that the organization fulfills its responsibilities and maintains adequate staff to do so.

- The Legislature should consider whether to make structural changes to the EMSRB board. It should also clarify what constitutes a conflict of interest for EMSRB board members.

As the legislature discusses and considers these recommendations, we ask that they also consider:

- The primary service area framework established by Minnesota was appropriate for its time and provides the necessary foundation for rural EMS to take the next step. The legislature should consider programs that provide incentives for neighboring EMS agencies to discuss collaboration and consolidations for the purpose of sharing resources and increasing their population pool from which to draw revenues and volunteers.

- Provide resources that help ensure all agencies are professionally managed.

- Conduct research on the threshold of call volumes vs. full-time staff. If standards require full-time staff at a certain level, then provide the gap in revenue needed to hire someone.

- In creating eligibility requirements for providing support to an agency, use multiple variables to measure severity of challenges. Try to avoid overly simplistic measures based on one variable, like call volume.

- Do not develop a one-size fits all set of performance standards. Rather, develop a tiered system where performance standards consider geographic size, call volume, reliance on volunteers, and level of service that an agency can feasibly provide.

Reports that recommend the legislature make significant changes by putting in place statewide standards will always make rural Minnesota nervous. Typically, the changes that are discussed and passed are metropolitan focused and the standards that need to be met are not attainable due to the age-old challenge in rural Minnesota—economies of scale.

However, with some forethought and an awareness of unique rural factors, policymakers should be able to craft a new structure for the state’s ambulance services that gives every agency the ability to function properly and provide their clients the services they need.

Works Cited

Institute of Medicine. Emergency Medical Services: At the Crossroads. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2007. https://doi.org/10.17226/11629.

King, Nikki, Marcus Pigman, Sarah Huling, Bs- Arrt, and Brian Hanson. “EMS Services in Rural America: Challenges and Opportunities,” n.d., 14.

Lukens, Jenn. “Recruitment and Retention: Overcoming the Rural EMS Dilemma.” The Rural Monitor (blog), February 7, 2018. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/rural-monitor/ems-recruitment-retention/.

Minnesota Department of Health. “2016 Rural EMS Sustainability Survey Results,” 2016. https://www.health.state.mn.us/facilities/ruralhealth/flex/docs/pdf/2016ems.pdf.

Mueller, Keith, Andrew Coburn, Alana Knudson, Jennifer Lundblad, Timothy D McBride, and A. Clinton MacKinney. “Characteristics and Challenges of Rural Ambulance Agencies – A Brief Review and Policy Considerations.” RUPRI Health Panel. Rural Policy Research Institute, January 2021. https://rupri.org/wp-content/uploads/Characteristics-and-Challenges-of-Rural-Ambulance-Agencies-January-2021.pdf.

Randall, Judy. “Emergency Ambulance Services – Evaluation Report.” Program Evaluation. Minnesota: Office of the Legislative Auditor, February 2022. https://www.auditor.leg.state.mn.us/ped/pedrep/ambulance.pdf.

“Rural Project Examples Addressing Emergency Medical Services – Rural Health Information Hub.” Accessed April 12, 2021. /project-examples/topics/emergency-medical-services.

[1] Randall, “Emergency Ambulance Services – Evaluation Report.”

[2] Mueller et al., “Characteristics and Challenges of Rural Ambulance Agencies – A Brief Review and Policy Considerations.”

[3] Institute of Medicine, Emergency Medical Services: At the Crossroads.

[4] King et al., “EMS Services in Rural America: Challenges and Opportunities.”

[5] Institute of Medicine, Emergency Medical Services: At the Crossroads.

[6] Mueller et al., “Characteristics and Challenges of Rural Ambulance Agencies – A Brief Review and Policy Considerations.”

[7] “Rural Project Examples Addressing Emergency Medical Services – Rural Health Information Hub.”

[8] Minnesota Department of Health, “2016 Rural EMS Sustainability Survey Results.”

[9] Lukens, “Recruitment and Retention.”

[10] Mueller et al., “Characteristics and Challenges of Rural Ambulance Agencies – A Brief Review and Policy Considerations.”

[11] P value < .05 using Pearson’s Chi-squared test

[12] Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor, “Emergency Ambulance Services,” February 2022, 51.

[13] P value < .05 using Pearson’s Chi-squared test.

[14] P value < .05 using Pearson’s Chi-squared test.

[15] Minnesota Department of Health, “2016 Rural EMS Sustainability Survey Results.”

[16] Statistically significant – P value < .05 using Pearson’s Chi-squared test

[17] Statistically significant – P value < .05 using Pearson’s Chi-squared test

[18] Statistically significant P value < .05 using Pearson’s Chi-squared test

[19] Randall, “Emergency Ambulance Services – Evaluation Report.”