by Tom Teigen

Nine new utility poles stand on Dale and Julie Schwartz’s dairy farm near Arlington, Minnesota, 60 miles southwest of Minneapolis. The 150-foot steel poles, stitched together by 345-kilovolt electric transmission wires, are part of the largest expansion of Minnesota’s power grid in more than 30 years.

“We didn’t even have a telephone pole on our property,” Julie Schwartz said, explaining how rural the landscape was before the power lines went up last year. They’re looking for a new place to farm now. “But we can’t just pick up our dairy farm and move it. You need buildings and land. There’s no place like ours in the area.”

The Schwartzes are among more than 2,000 Minnesota landowners, along with thousands of their neighbors, who are finding themselves beneath hundreds of miles of new high-voltage power lines.

Planning for the new lines began a decade ago, driven by an aging infrastructure, an increasing demand for electrical energy, the evolution of regional, multi-state power systems, and renewable energy mandates. “There wasn’t just one particular need,” said Tim Carlsgaard, a spokesperson for CapX2020, a joint venture by 11 electrical transmission companies. (See Sidebar: CapX Recap.) “There were a number of needs that all the participating utilities shared.”

Growing the grid: local to regional, traditional to renewable

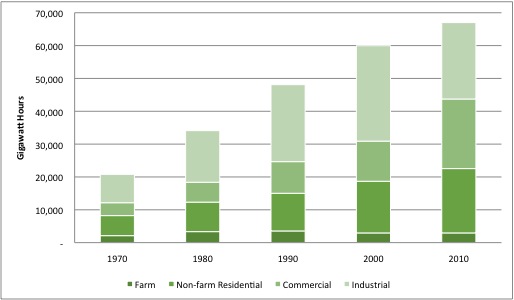

Minnesota’s consumption of electrical power has more than tripled in the last 45 years (See Figure 1[i]).

Source: Department of Commerce, Minnesota Utility Data Book

The 1960s and 1970s saw a major increase in the demand for electricity as the population grew and televisions, air conditioners, and kitchen appliances became commonplace household items. (Power demand grew by 64% just during the 1970s.[ii]) Minnesota’s hundreds of isolated local electric utilities responded by partnering on larger, centralized generating plants. A 2010 discussion paper by the Minnesota Department of Commerce noted how “rather than purchase large parcels of land closer to customers, utilities tend to site these [power] plants in fairly rural areas (at least ‘rural’ at the time that they were built) and then construct power lines to connect the power plants to customers.”[iii] As the plants were built, larger transmission lines started moving power to the state’s more populous communities such as Rochester, Mankato, St. Cloud, Duluth, and the Twin Cities.

But even as the size of the average home grew and home computers and flat-screen TVs became increasingly prevalent, often consuming power around the clock, state conservation efforts and federal energy efficiency standards have slowed the growth of electrical consumption. These standards now cover 90% of home electrical use, 60% of commercial use, and 29% of industrial use.[iv] While overall demand is still going up, particularly in the non-farm residential and commercial categories, the rate of growth in electricity demand has slowed. When CapX2020 applied for a Certificate of Need from the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission (PUC) in 2007, the organization projected electricity use to grow at an average annual rate of 2.49%.[v] Carlsgaard said estimates of annual growth rates, which individual utilities file annually with the PUC, are currently averaging around 1%.

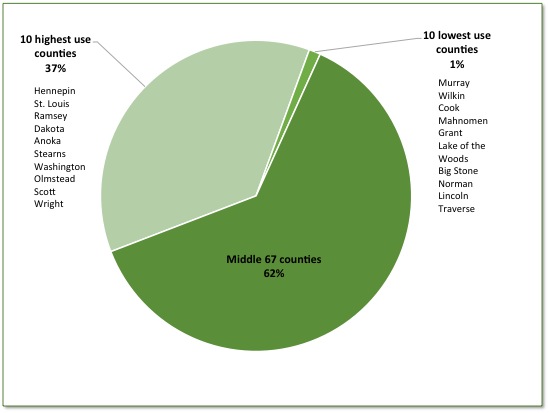

Today, more than 17,000 miles of transmission lines make up Minnesota’s electrical grid,[vi] and just 10 counties account for more than a third of electricity consumed in the state. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2: Minnesota electric consumption by county groups, 2010.

Source: Minnesota Department of Commerce. Minnesota Utility Data Book.

In the mid-1970s, a high-voltage power line from North Dakota to the outskirts of the Twin Cities generated protests in central Minnesota. Angry about living beneath power lines that served the urban areas, farmers used civil disobedience to delay construction and acts of vandalism to topple towers.

“It was the most contentious atmosphere in rural Minnesota that I’d ever witnessed,” recalled former state senator Gene Merriam. “The perception was that the legislature had to deal with it.”

The Legislature responded in 1977 with the “Buy the Farm” law. Authored by Merriam, the law required utilities to propose at least two possible routes for high-voltage transmission lines and increased public involvement in the process. The law also allowed property owners to force utility companies to buy an entire piece of property, not just the easements necessary for the high-voltage transmission lines.[vii]

“It was about balancing public needs with individual property rights. But you can’t simply have individual rights trump these kinds of projects,” said Merriam, the law’s chief author. “We recognized that [requirements imposed under “Buy the Farm”] could increase the cost, but it would be shared by rate payers who benefit from the lines.”

The law lay dormant for nearly 35 years as utilities focused on smaller projects and grid efficiency. But during that time the power industry itself was changing. Federal deregulation in the 1990s split the business of power generation off from the business of transmission. Nonprofit independent system operators (ISOs) formed to manage the high-voltage transmission lines that would serve as “interstate highways” for electric power and enable the creation of regional wholesale markets for electricity.

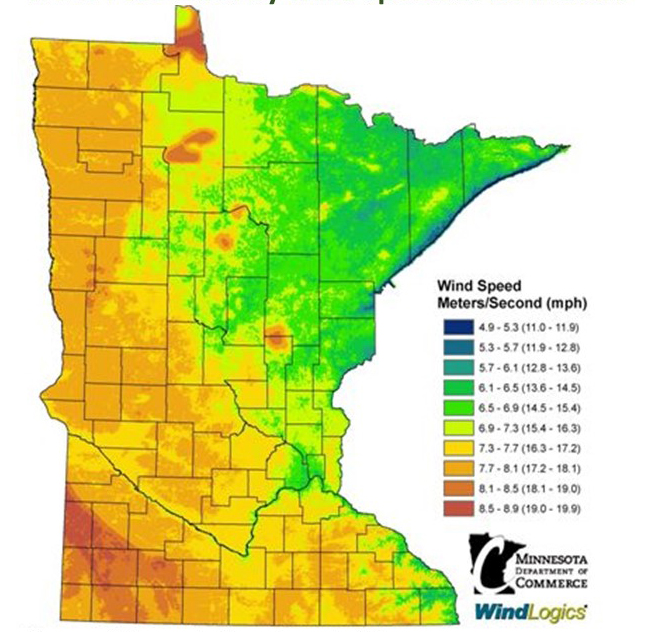

In the meantime, renewable energy was also coming into its own. The federal government created production and investment tax credits to encourage the creation of independent companies that would sell “green energy” to the market.[1] In Minnesota, state lawmakers transformed the state’s renewable energy incentives into goals and eventually mandates.[2] As a result, Minnesota law now requires that renewable energy account for 25% of all electricity consumed in Minnesota by 2025. Xcel Energy, Minnesota’s largest utility, faces a higher standard: 30% of its electricity needs to come from renewable energy by 2020. Most of that energy is expected to come from wind, with 1.5% required to come from solar energy. In 2013, the Legislature authorized a study that will explore increasing the renewable energy standard to 40%.

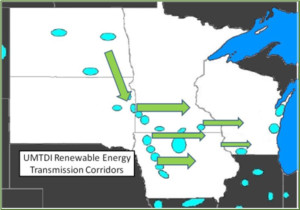

“Minnesota’s Renewable Energy Standard (RES) has become the most significant driver to expand the transmission network in the upper Midwest,” states the 2009 Capacity Validation Study, prepared by Minnesota utilities.[ix]

Meanwhile, independent wind farms not owned or operated by traditional utility companies sprouted up in southwestern Minnesota and the Dakotas, where the wind blows strong but the transmission grid is weak. During the past decade, independent power production in Minnesota more than doubled, reaching nearly 15% of overall power production in 2012, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.[x]

In 2004, several Minnesota utilities created CapX2020 as a joint venture and began working with state officials and regional organizations on the next major expansion of the power system. With electricity use falling during the Great Recession, CapX2020 opponents challenged the need for the project when, in 2007, CapX2020 along with 11 participating utilities, filed their application for a Certificate of Need with the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission (PUC). The PUC, however, rejected the argument and approved the Certificate of Need in May 2009, deciding that the project was necessary to meet community reliability needs, regional reliability needs, and to accommodate for additional wind energy.[xi] Between 2009 and 2011, the PUC issued route permits for each of the individual lines. (For a more detailed review of the process, see “Public Policy and Electricity Transmission Lines in Minnesota” in this issue of the Rural Minnesota Journal.)

Preparing a pathway: $160 million worth of easements

Hundreds of miles of new power lines would now need to be built across land owned by 2,000 property owners. (See sidebar “CapX Recap.”) High-voltage lines require 150-foot-wide rights of way, although the width varies with the voltage and pole construction. Rather than buy hundreds of miles of narrow strips of land, utilities purchase easements, which define the piece of land and the rights and restrictions that go with it for both the utility and property owner. Easements are binding on the utility, landowner, and any future owners.[xii]

Property owners retain ownership of the property and can continue to use it, as long as they abide by the restrictions. Power line easements, for example, typically limit tree height, building construction, and storage of flammable materials, according to a CapX2020 fact sheet.[xiii] Carlsgaard estimates that CapX2020 will spend $160 million to acquire the necessary easements for the entire project.

As utilities design the lines, they request access to property to take soil borings and conduct preliminary surveys prior to finalizing the plans. The rights of way on the power line routes approved by the PUC are wider than necessary, giving the utilities and property owners some flexibility in pole placement.

“Placement of poles can be an issue for farmers. Unless poles are placed in the corners of fields, they create dead zones that you can’t get to with modern equipment,” said Igor Lenzner, an attorney with the St. Cloud-based law firm Rinke Noonan, which has worked with nearly 100 property owners affected by the CapX2020 project. “CapX says they’ll work with property owners. But if engineering says that’s where the pole goes, that’s where the pole goes.”

When planning is complete, the utility offers property owners compensation based on a percentage of their property’s fair market value, plus incentive payments to encourage owners to settle. So far, CapX has acquired about 90% of its easements through negotiations, said Carlsgaard.

State law favors utility companies, however. When an agreement can’t be reached, utilities, as “public service corporations,” can take property for public purposes under Minnesota’s eminent domain statute.[xiv] To proceed with condemnation, the utility files a petition with the district court where the property is located. The district judge then appoints three independent commissioners—real estate agents, developers, appraisers—who will decide the compensation. The question at this point isn’t whether the utility will get the easement but how much the property owner will be paid in compensation.

Condemnation has been rare in counties like Lincoln and Clay, where the CapX lines cross vast stretches of farmland, Carlsgaard said. In more populated counties like Dakota and Scott, condemnation may account for 40% of acquisitions.

“The condemnation rates were higher in some areas because the project was under tight timelines,” Carlsgaard said. “So we used the quick-take option to keep the projects moving.”

Because it takes time to select panel members and coordinate schedules, Lenzner said, condemnation can take a year or more. The quick-take option gives the utility access to the property 90 days after filing for condemnation. Work often begins—and sometimes ends—before a final settlement is reached.

Surveyors, inspectors, drill rigs, concrete trucks, and cranes driving across someone’s property can be hard for people. “By the time the [condemnation] hearing comes, they can be frustrated and angry,” Lenzner said. “But when it’s over, for the most part, they feel like they’ve been given a fair shake. They got their day in court and were able to tell their story.”

Some property owners argue that CapX has been stalling the process, hoping to reach agreements before condemnation is complete. Carlsgaard acknowledges that condemnation can be long and frustrating, but he rejects the stalling charge. “It’s a good process,” he said. “With farmland selling at a premium, condemnation commissions have been awarding very high payments.”

Changes to Minnesota’s eminent domain law in 2006 and again in 2010 increased condemnation payments to property owners. Under those changes, utilities must compensate owners for appraisals, loss of an ongoing business, relocation costs, and attorneys’ fees if the utilities’ initial offer is substantially less than the final award. All told, some owners will receive five- and even six-figure payments for their easements.

“I understand that this is a burden on people,” Carlsgaard said. “But there’s this impression that we pay nothing, or very little to landowners. That’s simply not true.”

Attorney Lenzner claims a different experience, however: “I don’t know of anyone who wouldn’t give every penny back if they’d take the power line down.”

CapX buys the farm

For some people who don’t want to live near a high-voltage power line, Minnesota’s “Buy the Farm” law offers a way out. The only law of its kind in the nation, it applies exclusively to electric utilities building power lines with a capacity of 200 kV or more. The law enables people who own homes, farms, apartments, cabins, and resorts[3] to force the utility to purchase “any amount of contiguous, commercially viable land.”[xv]

“Buy the Farm”hasn’t had a huge impact on CapX. Carlsgaard estimates CapX will purchase additional property from 110 to 120 landowners, then sell those properties with the goal of recovering 80% of the cost. As the economy has improved, so have the prices. “We have people calling us, asking about buying some of these places,” Carlsgaard said.

While Buy-the-Farm numbers seem relatively small, however, the impact on individual property owners is large. Passionate arguments over how the law should be applied wound up on court dockets and legislative agendas, eventually reaching the State Supreme Court and the governor’s desk.

In 2011, several property owners in Stearns County elected to have CapX purchase additional property under “Buy the Farm.” CapX agreed to purchase the property but argued that the owners were not entitled to additional relocation and minimum compensation benefits. CapX attorneys contended that the owners were “choosing” to move, not being “forced” to move. Because the Legislature didn’t specifically address the issue when lawmakers amended Minnesota’s eminent domain law, those changes didn’t apply to “Buy the Farm,” they maintained.[xvi]

In May 2011, the district court ruled in favor of the property owners, awarding relocation and minimum compensation benefits. In August 2012, the Appeals Court reversed the decision. The Minnesota Supreme Court settled the issue on May 29, 2013, ruling that the property owners were indeed entitled to relocation and minimum compensation benefits.[xvii],[4]

State lawmakers also addressed the issue in 2013. Legislation authored by Rep. David Bly (DFL-Northfield) clarified that property owners have the same rights and protections under “Buy the Farm” as they do under other condemnation proceedings. The legislation also specified that when the utility challenges a “Buy-the-Farm” request on the grounds that the property is not commercially viable, the utility is responsible for proving the claim. Addressing complaints about the process, the legislation also imposed deadlines for the process.

Julie Schwartz, along with other landowners, testified in support of the legislation. Gene Merriam also spoke in favor of the changes, which he said made the law consistent with the original legislative intent.

CapX2020 has settled and paid dozens of property owners under “Buy the Farm,” Carlsgaard said. Dozens more are in the condemnation process. Some are going well, while others have become contentious.

More to come?

The CapX2020 projects in Minnesota are winding down. Land acquisition in southeastern Minnesota is nearing completion and the final stretches should be up and energized next year. But the expansion of Minnesota’s electric grid isn’t complete.

Dozens of projects can be found on the Department of Commerce docket, including two additional high-voltage projects.[xviii]

CapX2020 member Minnesota Power, in partnership with Manitoba Hydro, has proposed building a 500-kV line that would run from the Canadian border north of Roseau 240 miles southeast to Grand Rapids. A second 345 kV line from Grand Rapids to Duluth has been put on hold, according to the project’s website.[xix]

Along the Iowa border in southwestern Minnesota, ITC Midwest is planning a 345-kV line that would run 75 miles from Lakefield east to Winnebago, then south and east to Waterloo and Mason City, Iowa.[xx] Ultimately, wind energy from Minnesota and South Dakota could find its way to Illinois, another state with a 25% renewable energy mandate.

Just across the border in Wisconsin, CapX2020 member Xcel Energy and American Transmission Co. have proposed to stretch a 345-kV line from La Crosse to Madison. The Badger Coulee Transmission Line would, among other things, “establish another pathway for renewable energy into Wisconsin.”[xxi]

Common threads running through each of these projects, and similar projects around the region, include an increasingly regional, bordering on national, approach to energy transmission; an aging, inadequate grid; steadily growing demand for more energy; rapidly growing demand for renewable energy; and hundreds of property owners living in the shadow of high-voltage power lines carrying electricity from one part of the region to another.

As for the Schwartzes, the attorneys are still arguing over how much property will be purchased, the value—and who is responsible for the delays. “We’d give anything if they’d just move and leave us alone,” said Julie.

[1] The CapX2020 Interim Report (2004) provides summary of these changes.

[2] The 2012 Energy Policy and Conservation Quadrennial Report published by the Minnesota Department of Commerce provides an overview of state policies that have encouraged the growth of renewable energy production. [Insert link]

[3] The law specifies “private real property that is an agricultural or non-agricultural homestead, non-homestead agricultural land, rental residential property, and both commercial and non-commercial seasonal residential recreational property.”

[4] Attorneys also watched another eminent domain case, The County of Dakota v. Cameron, which involved highway construction and a liquor store. The case turned on definitions of “comparable property” and “community.” The Minnesota Supreme Court ruled on the case in November 2013.

[i] Minnesota Department of Commerce. (2010.) Minnesota Utility Data Book. Pages 9-10.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Offices of Energy Security and the Reliability Administrator, Minnesota Department of Commerce. (2010.) Minnesota’s electric transmission system – now and into the future. P. 5

[iv] Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Appliance & Equipment Standards: History and Impacts. (Accesses April 2014.)

[v] CapX2020. (August 16, 2007.) Certificate of Need Application. Chapter 6, Page 6.

[vi] Minnesota Electric Transmission Planning. (November 1, 2013.) Transmission Projects Report 2013: Transmission-owning Utilities.

[vii] Office of the Revisor of Statutes. Laws of Minnesota for 1977.

[viii] Upper Midwest Transmission Development Initiative Executive Committee Final Report, (September 29, 2010.) Page 10.

[ix] Minnesota Transmission Owners. (March 31, 2009.) Capacity Validation Study. Page 8.

[x] U.S. Energy Information Administration. (December 18, 2013.) Minnesota State Profile and Energy Estimates. (Accessed March 2014.)

[xi] Minnesota Public Utilities Commission. (May 22, 2009.) In the Matter of the Application of Great River Energy, Northern States Power Company (d/b/a. Xcel Energy) and Others for Certificates of Need for the CapX 345-kV Transmission Projects. DOCKET NO. ET-2, E-002, et a/./CN-06-1115.

[xii] Minnesota Department of Commerce (June 3, 2011.) Fact Sheet: Rights-of-Way and Easements for Energy Facility Construction and Operation. Page 1.

[xiii] CapX2020. (May 5, 2009.) Understanding Easements and Rights-of-Way.

[xiv] Office of the Revisor of Statutes. (2013.) Minnesota Statutes Chapter 117.

[xv] Office of the Revisor of Statutes. (2013.) 2013 Minnesota Statutes: 216E.12 Eminent domain powers; power of condemnation.

[xvi] Fredrickson & Byron, P.A. (May 6, 2011.) Petitioners’ Memorandum in Opposition to Carol A. Stice and David C. Shore’s Motion Regarding Chapter 117 of the Minnesota Statutes (Parcels MQ015 and MQ016).

[xvii] Minnesota Supreme Court. (May 29, 2013.) Northern States Power Company Board of Directors v. Aleckson et.al.

[xviii] Minnesota Department of Commerce. Project Docket. (Accessed March 2014.)

[xix] Great Northern Transmission Line. (Accessed March 2014.)

[xx] ITC. Minnesota-Iowa 345 kV Electric Transmission Project page. (Accessed March 2014.)

[xxi] Xcel Energy (October 22, 2013.) ATC and Xcel Energy file state regulatory application to build Badger Coulee Transmission Line Project.