September 2016

By Marnie Werner, Research director

A crisis has been quietly brewing throughout Minnesota and the nation for many years now. People have been getting out of the in-home family child care business at a disturbing rate, creating a severe shortage over most of the state. And while statewide data makes it appear that growth in child care centers is picking up the slack, that is not the case in much of Greater Minnesota.

Decisions regarding child care—whether to stay home with the kids or find care for them outside the home—has always been considered a personal decision, part of the “family bubble,” as Frameworks Institute puts it in their ongoing study of American attitudes toward child care.[1] This perspective, though, has perhaps been camouflaging the growing issue, keeping it out of the public eye. The reality is that the shortage is creating a ripple effect with very real impact, not just on families but on employers and entire communities, and the impact is being felt across the state.

Digging down through the data uncovers the complexity of the issue:

- The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that in 2014, 74% of Minnesota households with children under age 6 had all parents in the workforce, third highest in the nation behind Iowa and South Dakota at 75%.

- The change in the number of children age 0-4 between 2000 and 2015 varies from county to county, but the percentage of the total population they represent in each county has stayed remarkably steady, around 5% to 7%. In each county, that percentage barely changed over time, varying between a 2-percentage-point drop and a 1-percentage point increase. Only in Mahnomen County did the under-5 group increase by more than 1 percentage point, going from 7% of the population in 2000 to 10% in 2015.[2]

- Between 2006 and 2015, the number of licensed in-home family child care providers decreased by more than one quarter (27%) across the state. In terms of capacity—the total number of children providers are licensed to care for—that translates to a loss of approximately 36,500 spaces.[3]

- Over those same ten years, the number of child care centers increased by 8% statewide and their capacity grew by 27%, enough to fill about two thirds of the gap left by in-home providers exiting the business.

However, that statewide figure masks a huge divergence:

- Most of the growth in center-based care in the last ten years occurred in the Twin Cities seven-county area. Center-based care capacity in the Twin Cities increased by 31%, or 19,400 spaces, more than enough to make up for the 16,000 in-home care spaces lost. In Greater Minnesota, center-based capacity increased by only 18%, or 5,039 spaces; in-home family child care capacity, in fact, decreased by 20,400 spaces for a net loss of more than 15,000 spaces.

The change in the number of licensed child care providers between 2006 and 2015 and the capacity they represent (MN Dept. of Human Services).

|

FCC |

CCC |

Net change |

|

|

Greater MN |

-20,416 |

5,039 |

-15,377 |

|

Twin Cities |

-16,125 |

19,409 |

+3,284 |

Capacity: The change in the number of spaces in in-home family child care (FCC) and center-based child care (CCC) between 2006 and 2015 (MN Dept. of Human Services).

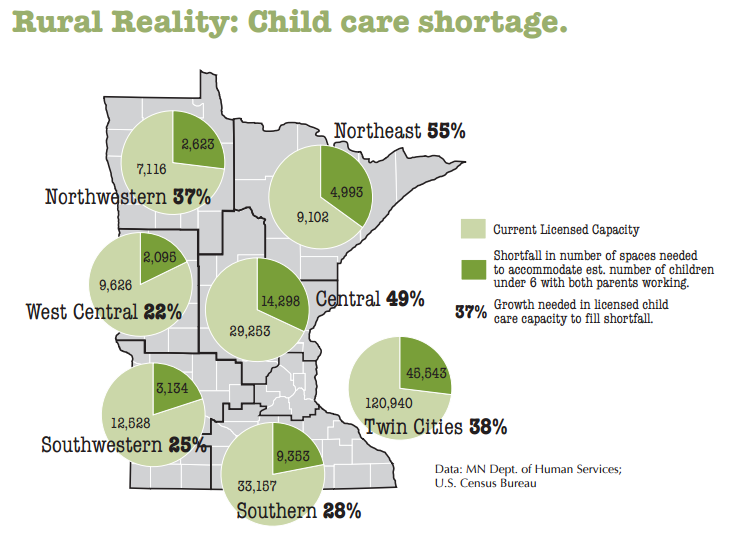

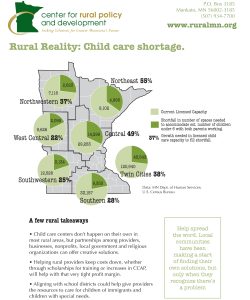

- Even with the growth trend in child care centers, every region of the state still shows a shortfall between the number of children potentially needing child care and the number of spaces available.

Looking past the data reveals a situation affecting family incomes and business productivity everywhere in the state.

- Infants are by far the most difficult age group to find care for. The supply of infant care spots is now squeezed to a point where it is not unusual for families expecting babies to contact dozens of providers only to come up empty or be put on waiting lists of several months to a couple years. This has serious implications for women who would like to go back to work after the birth of their child.

- Low-income families and single-parent families are particularly hard hit. Low-income parents are more likely to not have paid leave, while single parents have no second parent to share care with or second income to fall back on if something happens to their child care. The loss of child care can mean the loss of a job, thus hurting the family further financially.

- Parents of children with special needs and parents who work non-traditional shifts have almost no choices for licensed child care.

- Most of Minnesota is facing an unprecedented shortage in skilled labor. Employers are working hard to find talent, but recruits are turning down jobs in places where quality child care is unavailable or unaffordable.

- In rural areas it’s not unheard of for a parent to drive upwards of 40 miles round trip, from home to another community to drop their child off with a provider, then to another community for work. It’s also not unusual to have children from one family at multiple locations.

Losing child care: the ripple effect

The mass exodus of in-home family child care providers from the business is alarming, but the reasons are understandable: providers can’t make a living at it. Salaries and wages in child care are a huge deterrent for would-be providers, especially when they have student loans to pay off and the job offers few to no benefits, says Nancy Jost, an early childhood specialist at West Central Initiative in Fergus Falls.

“They can’t make a living wage at it, so they don’t go into it,” Jost says.

More than 85% of child care workers would be considered low-wage workers, making less than $20,000 annually, says a 2014 article from the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development.[4] The federal poverty line for a family of three that year was $19,890.[5]

Considering the level of education many providers have, they are still woefully underpaid, says a 2015 report from the National Academy of Sciences on the child care workforce.[6] It’s no wonder that many women holding an early childhood education license will quit child care and move into K-12 teaching positions as soon as the opportunity arises, says Jost. (And according to a 2011 report by the Minnesota Department of Human Services on the child care workforce, virtually all child care providers in Minnesota are women.[7])

In areas like Thief River Falls, where companies are offering $16 an hour and full benefits and are still begging for employees, child care providers find it hard to resist switching careers, says Vicky Grove, child care specialist at the Northwest Minnesota Foundation.

Each provider leaving the profession, however, creates a ripple effect. “One employer told me, when she hires a woman, she really hopes that woman wasn’t a child care provider, because if she was, [the employer] can expect calls from eight employees telling her they just lost their child care,” Grove says.

The solution may seem to be to pick up some of the slack through proposed pre-kindergarten programs, but taking four-year-olds into the public school system could put even more financial pressure on licensed child care providers.

As a general rule, among newborn to five-year-olds, infants are the most expensive to care for mostly because they require the highest staff-to-child ratio. Providers break even on toddlers and make a profit on preschoolers so they can lose money on infants, says Heidi Hagel Braid of First Children’s Finance, a Twin Cities-based nonprofit that helps child care providers learn how to run their in-home family child care like a business. Removing four-year-olds from the pool would simply worsen the situation.

The child care shortage hits families first. Jodi Maertens, a program officer focusing on child care at the Southwest Initiative Foundation in Hutchinson, knows this firsthand. Maertens was caught without care for her 11-month-old this summer when her child care provider made the decision to go back to school. Maertens found another provider who could take her child in September, so Maertens and her husband took days off and arranged babysitters to cover the month in between.

Maertens counts herself lucky, though, that it was only a month. For single parents with no one to fall back on or those who can’t get child care on a regular basis, like people working non-traditional shifts, it would be like this all the time.

“This is only my second week at it [without child care], and I’ve already fallen behind at work,” she says. “Every morning, it’s like, what’s the plan for today?”

Child care represents a significant cost in most families’ budgets, according to Child Care Aware of America. Those costs compete with other necessities like housing and food. Comparing median household incomes to average child care rates by county,[8] an average annual child care bill can represent anywhere from 10% to 17% of that county’s median household income. Center-based care tends to be even more expensive, ranging from 10% of median household income in Renville County to 27% in Hennepin County. The Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development’s Cost of Living tool shows how child care factors in with other household expenses.[9] Child care or lack of it can dictate many things, like whether a parent can accept a job offer and which one, whether they can work at all, where they live, and how far they commute.

The Minnesota Department of Human Services staff is tracking the child care shortage, interpreting the data they have to better understand the situation. But while they collect data from providers, they lack solid data on the family side, says Deb Swenson-Klatt, manager for the child development services division of DHS, which leaves them constrained in their ability to help find solutions.

Certain groups are especially hard hit

Low-income families, in particular single-parent families, struggle with child care. “They don’t have as much stability with their options,” says Tammy Filippi, early childhood specialist with the Initiative Foundation in Little Falls. The cost of child care eats up a larger percentage of their income (see table), limiting where parents can take their children, but in small towns with few providers, they may have little choice. The table below shows the difference in impact child care has on different levels of household income.

|

Statewide |

|

Family child care |

Accredited child care center |

|

Average annual cost |

|

$8,033 |

$17,442 |

|

Median income, married couple |

$96,364 |

8% |

18% |

|

Median income, single mother |

$27,075 |

30% |

64% |

|

Median income, single father |

$41,283 |

19% |

42% |

Income data: U.S. Census 2014 estimates; Child care cost data: Child Care Aware of America, Minnesota 2015 fact sheet.

Low-income parents are also more likely to work multiple jobs and non-traditional shifts, for which child care is virtually non-existent. At that point, parents must turn to what’s known as FFN, their family, friends and neighbors.

The state’s Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP) helps low-income families pay for child care. Payments are made directly to providers on behalf of families. The problem is that program payments often don’t cover a provider’s full costs, says Barb Wagner, executive director of the Minnesota Licensed Family Child Care Association, Inc. Families are supposed to pay the difference, but they can’t always, or won’t. The provider is left trying to collect or taking a loss.

The percentage of different groups saying they feel they have to take whatever form of child care they can get (MN Dept. of Human Services, “Child Care Use in Minnesota: Report of the 2009 Statewide Household Child Care Survey.”).

Another group struggling with child care are families of children with special needs, who often require specialized services and extra attention.

“We hear from providers about this the most,” says Hagel Braid. Providers are seeking resources and training, especially anything that would strengthen the connection between child care and the special education resources of local school districts.

Different cultural groups look at child care differently as well. A 2009 survey by the Minnesota Department of Human Services found that nearly 60% of people of color said child care provided by a family member was “very important,” compared to 29% of all households.[10] Among immigrant families, mothers are more likely to stay home with the children, but when they do need child care, they look to family, friends and neighbors who understand their culture and language, says Hagel Braid.

There aren’t many bilingual child care programs yet, but communities are changing. Greater Minnesota’s many cities with large pockets of immigrants “should be positioning themselves to be vibrant communities,” Hagel Braid says.

“In the business of building brains…”

“As a society, we tend to overlook how children are being cared for in their first five years,” says Lynn Haglin, vice president of the Northland Foundation in Duluth and director of the foundation’s KIDS PLUS program.

Frameworks Institute’s research on Americans’ attitudes toward and understanding of early child development[11] found that we tend to look at children’s brains as little empty vessels to be filled up with information. Instead, it’s more like our brains at that age are being wired by our experiences, environment and relationships. From birth to age three, a baby’s brain makes up to 700 neuron connections a minute.[12] How they are wired early on will determine how a child progresses intellectually and emotionally the rest of his or her life.

With a shortage of child care or affordable child care, the fear among early childhood education professionals is that parents will be forced to turn to cheaper, lower-quality alternatives. Now with a shortage of providers, we need to make sure that what’s being offered out there is quality care, Haglin says.

Low-quality child care looks like groups of babies sitting in car seats all day and toddlers plopped in front of TVs for hours, day in and day out, says Haglin.

This type of supervision does nothing for a child’s brain development, which does nothing to prepare them for becoming adults, says Hagel Braid.

“They are the future workforce. Birth to five is the most important period for social and emotional development, and social and emotional development is what makes them good employees down the road,” Hagel Braid says.

Children receiving high-quality care, whether at home or from a provider, are far more likely to show up for kindergarten ready to learn. “If they’re not ready, it starts an achievement gap that’s incredibly hard to close later on,” says Hagel Braid.

What makes providing child care hard, she says, is that “child care providers are in charge of building brains, and they’re doing that without help or support because they’re privately owned businesses providing a public service.”

According to Haglin, however, being a licensed child care provider does not guarantee quality care.

“Licensing is only about basic safety, but parents think it’s about quality,” Haglin says. While licensors visit homes once a year to do important safety checks, they are not involved in curriculum or what children are doing all day.

To add that element of screening for quality, the state Department of Human Services and private partners introduced the Parent Aware Quality Rating and Improvement System to Minnesota in 2007 to help families locate quality child care and early education and to help providers improve their skills and knowledge. Parent Aware Star Ratings and other education services give parents tools and information to find quality programs. Higher Star Ratings indicate that providers are trained in best practices that prepare children for kindergarten. Local Child Care Aware agencies help providers participate in Parent Aware training.

The star rating system has been very helpful for providers, says Haglin, giving them new tools and strategies, and it can be a big morale booster for professionals who often feel undervalued. “They feel reinvigorated,” Haglin says.

The disconnect between expenses and income

The primary problem for child care providers, whether they offer in-home care or center-based care, is a fundamental gap between what it costs to run a child care program and what parents are willing or able to pay.

Ideally, a business owner sells a service or product at a price that covers the cost of producing that item, plus a little profit. At the same time, though, they can only charge a price the market will bear or else the market won’t buy. In the current market failure situation of child care, providers would charge rates that allow them to at least cover their costs, but many parents find it difficult to pay that much, especially in rural areas.

In some Twin Cities suburbs, where incomes are higher and children are plentiful, providers can make a reasonable income, says Barb Wagner. They can charge what they need to, and if a family can’t afford it, another family is willing to take—and pay for—that spot.

In rural areas, it is tougher for a provider to push that price up, Wagner says. Median household incomes are lower in rural areas (sometimes much lower), but the cost of providing child care isn’t necessarily lower.

For family child care providers, the largest portion of expenses, at 30%, goes toward facility costs such as home, phone, and utilities, says Hagel Braid. Another 22% goes toward administration costs such as licensing, training, supplies, curriculum, or accounting services. For child care centers, 70% of the cost of operation is in staff. Facility expenses take up another 20%; food, 5%; and everything else, another 5%.

Expense and frustration

Regulations keep children safe and hold providers accountable, but at hearings held by the Minnesota House Select Committee on Affordable Child Care in early 2016, providers repeatedly mentioned how regulations have become difficult to follow.[13]

“Child care is a highly regulated industry, and it should be,” says Hagel Braid, “but that comes with a price.”

In 2013, the Minnesota Legislature increased the number of annual training hours required for licensed providers from 8 to 16. This wasn’t an arbitrary decision. According to Minnesota DHS, “Minnesota’s focus on health and safety trainings is consistent with new training requirements being enacted throughout the country and federally.” New federal regulations require states to enact laws requiring licensed providers and providers who receive child care assistance payments to be trained in ten health and safety topics.

That’s a good thing, says Sherry Tiegs, who has over 30 years’ experience in child care and early childhood education in Morris. “It keeps providers up to date on the latest statistics and education in early childhood education and child development.”

For rural providers, however, getting in their required training can be a challenge. Rural Minnesota has a shortage of approved trainers, says Tiegs, who is an approved trainer herself. For providers, attending training can mean additional expense in gas and an overnight stay, and possibly closing for a day or two. Training sessions are also cancelled due to low numbers, which puts providers at risk of not getting in their required hours to stay licensed. Rural providers can take their classes online, but Internet access can also be an issue, say Tiegs.

Regulations also carefully control the number of children a family child care business can care for. They can be licensed for no more than ten children, and of those, no more than six can be under school age. Also, no more than three can be infants and/or toddlers, and of those, no more than two can be infants (less than 12 months old).[14] Keeping groups small is good, but it does inherently limit a provider’s income, which may be one reason why child care centers have been on the upswing. They have a staff, can handle larger numbers of children while reducing per-child overhead, and the owner can take days off without having to close down.

Child care centers aren’t easy to open in rural communities, though. Centers account for only 33% of child care capacity in Greater Minnesota and 67% in the Twin Cities. The cost of starting up and maintaining a center can be considerable, and smaller communities may not have the number of children needed to cover those costs. Expenses include staff, which are becoming increasingly hard to recruit, renting or purchasing space, and ongoing upkeep. Serving food at a center requires a restaurant-grade kitchen.

“It’s not just about opening a center but maintaining it,” Jost says.

Paperwork plays a role in the frustration as well. “Care for infants is especially at risk as the regulations have become so strict, providers are simply afraid to care for infants,” says Wagner of the Minnesota Licensed Family Child Care Association Inc.

Providers must collect intake forms, medical forms, immunization forms and more to accept children into their programs and keep track of crib checks and equipment checks.

“There are some providers that have chosen not to participate in the [Child and Adult Care Food Program], because they feel that for the amount of paperwork they do, the reimbursement they get is not worth the hassle,” says Wagner.

Inconsistency among county licensors is also a major headache, according to providers testifying before the House Committee on Affordable Child Care. County licensors, who enforce state regulations, are providers’ first and closest point of contact with the state, but licensors can have widely differing interpretations of those regulations, often catching providers by surprise.

“It has left many providers afraid to be in the business,” says Wagner.

Regulations are created by the state legislature but enforced by the Minnesota Department of Human Services. The department also supports delivery of much of the training available to providers in Minnesota through grants to organizations like First Children’s Finance and Child Care Aware agencies, but the programs need to be made more visible says DHS’s Swenson-Klatt. “We need to ensure [programs] are offered in the communities that need them most, especially in very rural communities.” This is where having only anecdotal information instead of fine, community-level data is a problem, says Swenson-Klatt. DHS’s resources are limited; they need to know where to focus them for best effect.

“We’re always looking at what modifications we can make in service delivery to remove barriers,” says Swenson-Klatt.

The challenge and potential for businesses and communities

At the same time that businesses are facing an unprecedented worker shortage,[15] the child care shortage is compounding the problem.

Reliable, quality child care in a community supports local business by giving parents child care they can count on. That in turn allows them to be undistracted and productive. Without adequate child care, local businesses are unable to recruit skilled workers and the workers they do have may be preoccupied with child care worries.

Child care is a top reason for absenteeism, and absenteeism hits the bottom line of every business in the form of lost productivity, the cost of bringing in temporary help, overtime for other workers asked to fill in, and the cost of finding and training a replacement if the parent quits.[16]

A sick child, a sick provider, or snow days are all reasons. In addition, parents who find their children’s current care inadequate and can’t find a suitable replacement may decide to quit work altogether to stay home.

Child care is such a desirable commodity now, in fact, that some Minnesota businesses are using it as a way to attract workers, especially younger workers. In manufacturing, one of Greater Minnesota’s strongest industries, a large percentage of baby boom-generation workers are nearing retirement. Rural manufacturers are having a hard time keeping up with growing demand for their products despite the fact the sector is paying $10,000 to $15,000 more than most other industries.[17]

Harmony Enterprises Inc. in Harmony, Minn., spent $500,000 to convert a factory next to its plant into a 10,000-square-foot child care center for 100 children. The manufacturer of recycling and waste management equipment was struggling to find employees. They saw offering child care as a way to stand out.[18]

According to company president Steve Cremer in a Star Tribune article, child care has been Harmony employees’ biggest issue. It causes stress when workers have to “‘leave mid-shift and drive 20-plus miles to collect kids when day-care arrangements fall through,’ he said.”

“‘Our day care will be most important for employee retention, but of course it will definitely help us with recruiting, too … It is just not easy to find people,’ Cremer said.”

Management at Gardonville Cooperative Telephone Association in Brandon, just up I-94 from Alexandria, came to a similar conclusion. In 2014, the co-op remodeled space in its old headquarters to provide care for children of employees and from the community.

In a local news article, CEO and general manager Dave Wolf challenged all business leaders to take a good look at child care as a benefit for employees. “A lot of our employees are two-income families and they’re young families. Child care is a very dynamic problem that’s shifting constantly.”[19]

First Children’s Finance has been working on ways to help towns come up with innovative community-based solutions, says Hagel Braid. The ideas have been big and small. Communities are using financial incentives; pairing business owners and providers to build sustainability; and eliminating some of the costs of training: in Stevens County, a dairy with good high-speed Internet service set up a room where providers could take online training, solving their problem of poor Internet service at home and having to travel long distances.

The Minnesota Initiative Foundations are also addressing this issue, working with Parent Aware and First Children’s Finance to help providers receive Parent Aware ratings by covering training costs and making training available locally.

First Children’s Finance has also been coordinating Greater Than MN, community planning projects that address the child care shortage. Providers, parents, educators, businesses, economic developers and local governments in Redwood, Itasca and Clay counties produced community action plans in 2015, and three more counties are currently going through the process, says Hagel Braid. In the plan, stakeholders identified the issues, their effects, and concrete steps for action going forward.[20]

Predicting the future

The population of zero to four year olds is projected to stay steady, right around 355,000, for the next fifty years, according to the Minnesota State Demographic Center.[21] The growth in the working-age population is expected to be similar, staying flat until around 2035, when it will begin to grow modestly. But even with no increase in child population, the steep downward trend in the number of licensed family child care providers promises no end to the shortage. That trend is simply market forces at work. For those child care providers getting out, the income they made did not offset the expense, time and effort they put into it.

But while the number of providers has dropped by one fourth in the last ten years, almost 10,000 licensed providers are still doing this vital job. Child care providers are transitioning from being considered glorified babysitters to being highly trained, dedicated professionals responsible for our future workforce and citizens. Those providers who are hanging on through these tough times, continuously improving their skills, and excelling at their jobs deserve to be treated as such.

What can be done to help them continue to provide quality child care, to convince others to take up this career, and to show them that they are a valued part of our society and economic system?

“It will not be a top-down or bottom-up solution,” says Nancy Jost. “If we don’t work on it as communities, we’ll have a hard time implementing anything. But without state policy, we won’t have lasting solutions. No one layer can figure it out on their own.”

Recommendations

- Ensure that policies don’t depend on growth in child care centers to fix the shortage everywhere. Child care centers are very difficult to open and maintain in rural areas and therefore can’t be counted on as the sole solution.

- Ensure that family child care providers are represented on committees and in other policy-making discussions, especially those that set regulations.Encourage state lawmakers to increase CCAP to a level that comes closer to covering providers’ costs.

- Support the Minnesota Department of Human Services in their efforts to make it easier to be a child care provider in Greater Minnesota. This includes making training more accessible and more affordable through Child Care Aware, Parent Aware, and other organizations; and their ongoing work to make their website more user friendly.

- Require that training for county licensors ensures they understand child care regulations, how to assist as well as enforce, and the importance of enforcing regulations consistently across the state.

- Track and study child care options for under-served groups: children of immigrants, children with special needs, and children whose parents work nights and non-traditional shifts. More information will help with the search for solutions

- Help with licensing costs or even offer free licensing. Such cost savings can mean the difference for a provider between staying in business or quitting.

- Help spread the word. Local communities have been making a start of finding their own solutions, but only when they recognize there’s a problem.

[2] U.S. Census.

[3] Minnesota Department of Human Services, FCC and CCC licenses and capacities 2006-2015.

[4] Amanda Rohrer, “Low Income Workers in Minnesota,” September 2014.

[5] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines.

[6] Allen, LaRue and Bridget B. Kelly, editors, Transforming the Child Care Workforce for Children Birth through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation, 2015.

[7] Minnesota Department of Human Services, “Child Care Workforce in Minnesota, Final Report.”

[8] Median household incomes, U.S. Census Bureau 2014 estimates; Average weekly child care rates, July 2016, Child Care Aware.

[9] MN Department of Employment and Economic Development, Cost of Living tool.

[10] Minnesota Department of Human Services, “Child Care Use in Minnesota: Report of the 2009 Statewide Household Child Care Survey.”

[13] Minnesota House of Representatives, House Special Committee on Affordable Child Care.

[14] Minnesota Administrative Rules, 9502.0367 Child/Adult Ratios; Age Distribution Restrictions.

[15] Center for Rural Policy and Development, “The Coming Workforce Squeeze.”

[16] Forbes, “The Causes and Costs of Absenteeism in the Workplace.”

[17] Star Tribune, “Rural factories spend big on perks, even buy companies to find workers.”

[18] Star Tribune, “Rural factories spend big on perks, even buy companies to find workers.”

[19] Echo Press (Alexandria), “Child care crunch causing parents to scramble.” Nov. 15, 2015.

[20] GreaterthanMN.org, “Redwood County Community Solution Action Plan.”

[21] Minnesota State Demographic Center population projections.