Feb. 27, 2019

Next week we’ll be releasing a new publication, “Letters to the New Governor,” a collection of essays written by people from around the state on various topics of importance to Greater Minnesota. One of those articles is on the current child care shortage, and the following is an excerpt. You’ll be able to find the full article next week on our web site at ruralmn.org along with more essays on topics varying from agriculture to the environment to population trends.

By Marnie Werner, Vice President, Research and Operations

When it comes to governing a state this size, there are quite a few issues policy makers have to deal with that sound the same at first hearing—road funding, access to health care, education funding. But as with the different landscapes around the state, it turns out the ways that problems can manifest themselves may be very different from one part of the state to another as well.

Take the child care shortage, for instance. Looking at the data on child care providers from the last twelve years or so, it’s apparent fairly quickly that family child care providers are the ones leaving the business. In both Greater Minnesota and in the Twin Cities area, both the number of providers and capacity have dropped by more than 25% since 2006.

The number of centers and the number of spaces for children those centers offer has been increasing over the same time period. Between 2006 and 2017, spaces at centers in the seven-county metro area increased by more than 24,000, more than making up for the loss in 18,000 FCC spaces.

In Greater Minnesota, however, a loss of more than 22,000 FCC spaces was offset by an increase of only 7,000 new center spaces. In other words, while the Twin Cities gained 6,000 child care spaces in that time period, Greater Minnesota lost more than 15,000.

What’s going on here? Why haven’t centers sprung up at the same rate in rural areas as they have in the Twin Cities?

To get to some answers, let’s look at three facts about child care in Minnesota.

- Economies of scale work against child care centers in rural, sparsely populated areas. This explains why centers provide 70% of child care capacity in the Twin Cities seven-county area but only 35% in Greater Minnesota, even when cities like Rochester, Duluth, St. Cloud and Mankato are included. There are several counties, in fact, that have no centers at all.

- Rates are suppressed because of lower incomes and sparser population. Although it could be attributed to lower cost of living, it’s more likely that on average, median household incomes are lower the more rural a community is, which in turn would lower a family’s willingness or ability to pay. This factor would hamper the sustainability of a child care operation with higher overhead costs compared to one with lower overhead costs.

- Pay is woefully low. Hovering around $10-$12 an hour, this rate creates a challenge for finding staff, especially in today’s climate where workers can find too many better-paying alternatives.

The question, therefore, is this: How can the state have the most effective impact on the child care shortage across the entire state while minimizing unintended negative consequences?

It’s a conundrum, but it can be helped with better information.

The Center recently conducted a survey of both FCC and CCC providers in both urban and rural Minnesota. We’re analyzing the data now, and while the early results have given us few surprises, they have also provided some specifics:

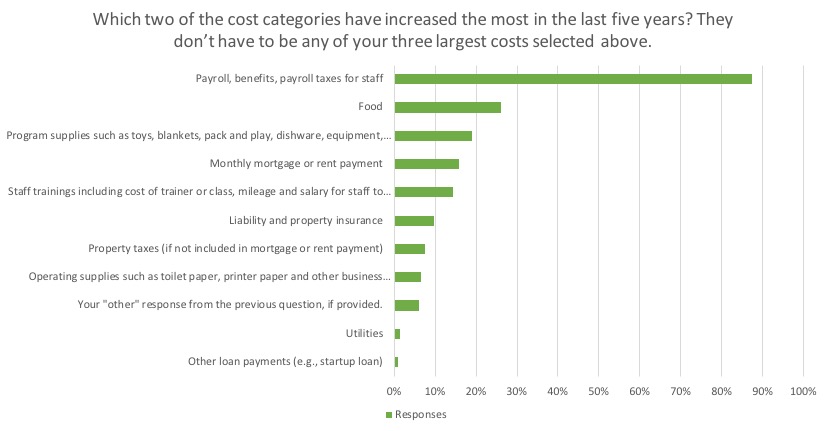

- Staffing is by far the biggest problem for CCC providers. Of the list of overhead costs we gave respondents to choose from, the cost of pay and benefits was chosen by over 80% of respondents as one of the top two expenses that have gone up the fastest in the last five years.

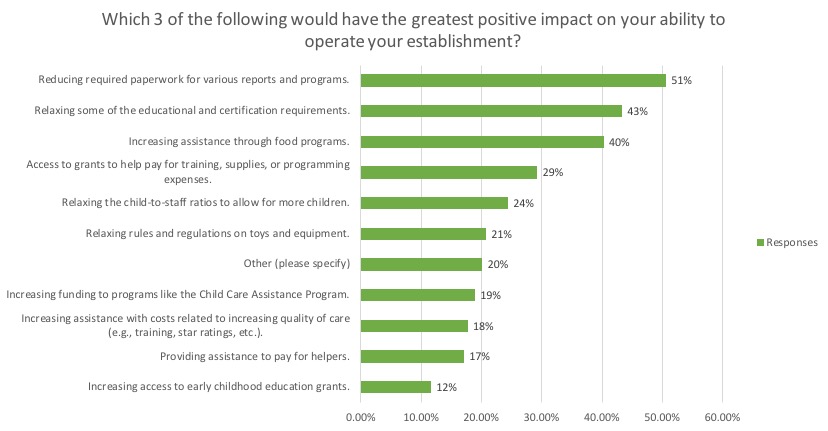

- Both FCC and CCC providers cited regulations as an issue, but when asked what three moves would have the greatest positive impact on their ability to provide child care, FCC providers ranked relaxing the amount of paperwork and the level of required certification and/or education the highest.

As we dig further into the data, we’ll get a better picture of the concerns of child care providers in both Greater Minnesota and the Twin Cities. In the meantime, we do know this about providing care in rural areas: Focusing on centers as a means of replacing family providers will be a tough go unless something can be done to lower startup and overhead costs while at the same time making pay more attractive.

But as we also explained above, hitting the problem with top-down solutions that are too specific or inflexible could just compound the problem, while not wanting to make a wrong move can cause paralysis.

Many leaders in many communities understand this and, rather than wait around, are going ahead and working on their own solutions. They are convening parents, local government, educators, churches, nonprofits and others to first identify what their community needs, then figuring out how to get there. In Benson, one solution has come through the school district, while in Harmony, a large employer in town, Harmony Inc., started its own child care center.

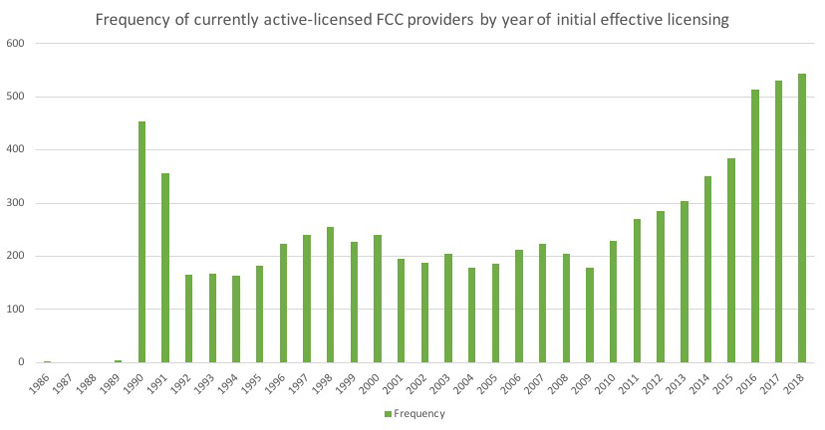

And we shouldn’t abandon the idea of growing the ranks of FCC providers. The chart below shows the number of FCC providers with active licenses at the end of 2018, grouped by what year they were first licensed. There’s a definite drop-off in the first few years, indicating that there are quite a few providers who start in the business but don’t stay in the business.

The fall-off could be attrition as a certain number of women decide the business isn’t for them. What the chart might be showing, too, though, is the well-known pattern of new mothers starting a family child care business and staying in for just a few years, until their own babies are old enough to start school. Is there a potential solution here as well?

What’s next?

The nature and extent of the child care shortage will require a major, long-term focus to fix it. It took at least two decades to get to this point, so it will not be fixed overnight. Fortunately, the state wields a great deal of power in the realm of child care, which means it also wields a great deal of power to help fix this problem. With the emphasis on help.

Essentially, the trick when it comes to solving the child care shortage across Minnesota will be this: Trying not to stifle innovation with good intentions. It will take a lot of work, but it should be possible for state-level policymakers to develop parameters for quality child care that allow communities to find solutions—whether for center or family child care—that work for them while maintaining the quality and safety we all desire.