Access to Mental Healthcare for Rural Minnesota’s Communities of Color

By Mitra Milani Engan, MME Consulting,

& Marnie Werner, Vice President of Research & Operations

November 2025

Rural Minnesota is changing. Across its small towns and open landscapes, people of color are becoming a larger part of the community—some newly arrived from other countries, others whose families have called this region home for generations.

As our previous research has shown (here and here), finding help for mental health concerns can be a struggle for anyone living in rural areas, but it can be even harder for BIPOC residents (Black, Indigenous and People of Color). Whether they are recent immigrants trying to navigate an unfamiliar system or long-time Minnesotans seeking care that understands their experiences, the challenges of finding accessible mental health services that meet their needs remain significant.

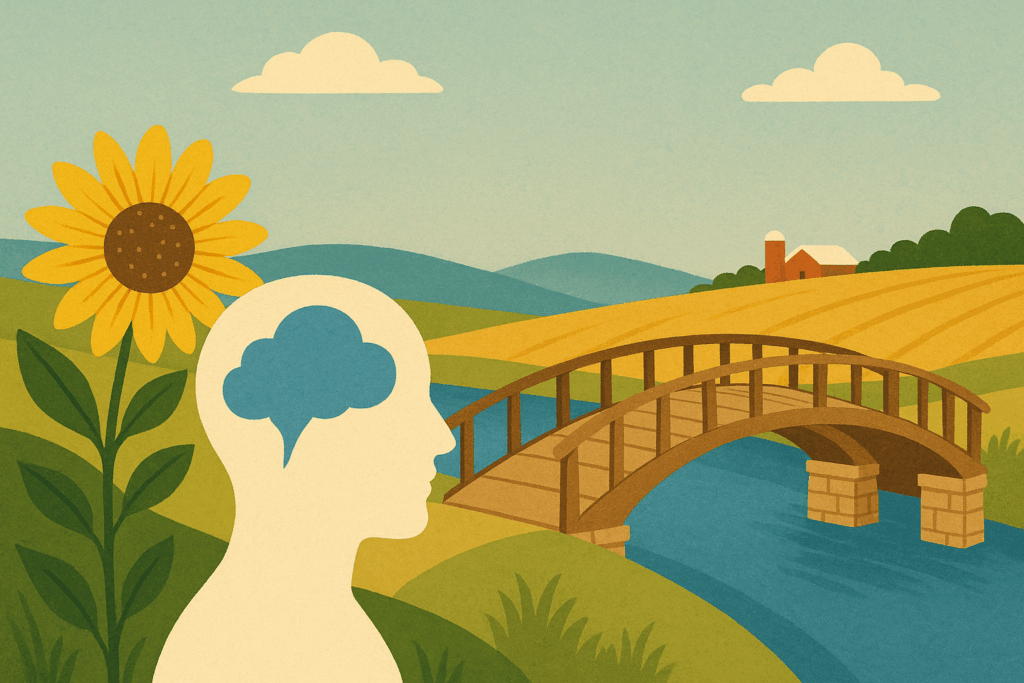

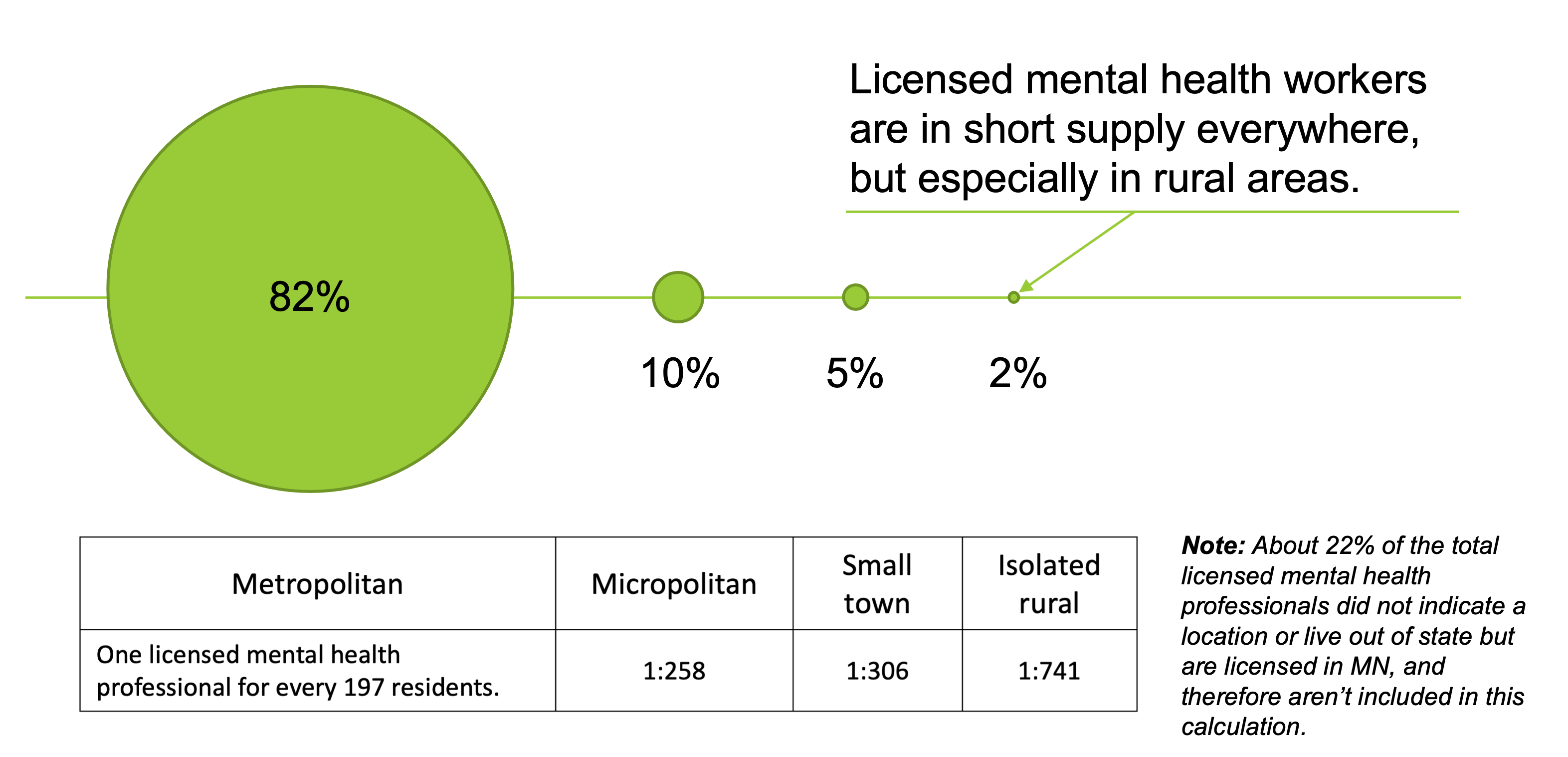

The acute shortage of mental health providers and services in Greater Minnesota is real.[1] The ratio of mental health care providers to residents shows just how much the supply of providers in Minnesota goes down as the population density of an area also goes down (Figure 1). And yet, demand is growing all the time (Figure 2 & Table 1).

Figure 1: In December 2022, 82% of licensed mental health providers lived and/or worked in the Twin Cities or one of the state’s larger cities. The licensed provider-to-client ratios vary considerably around the state. Center for Rural Policy & Development & MN Department of Health.

Figure 2: Reports of self-harm among U.S. adolescents have risen steadily, especially among girls, since 2010. Data: Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, WISQARS.

Table 1: The Minnesota Student Survey, taken every three years, shows a distinct increase in mental health concerns among 11th graders who participated in the survey. Source: Minnesota Student Survey, MN Department of Health.

| Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless? | ||

| 2016 | 2022 | |

| Not at all | 54.5% | 45.5% |

| Several days | 27.6% | 31.3% |

| More than half the days | 10.0% | 12.5% |

| Nearly every day | 8.0% | 10.6% |

| Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things? | ||

| 2016 | 2022 | |

| Not at all | 46.5% | 35.4% |

| Several days | 33.1% | 38.6% |

| More than half the days | 12.3% | 15.1% |

| Nearly every day | 8.2% | 11.0% |

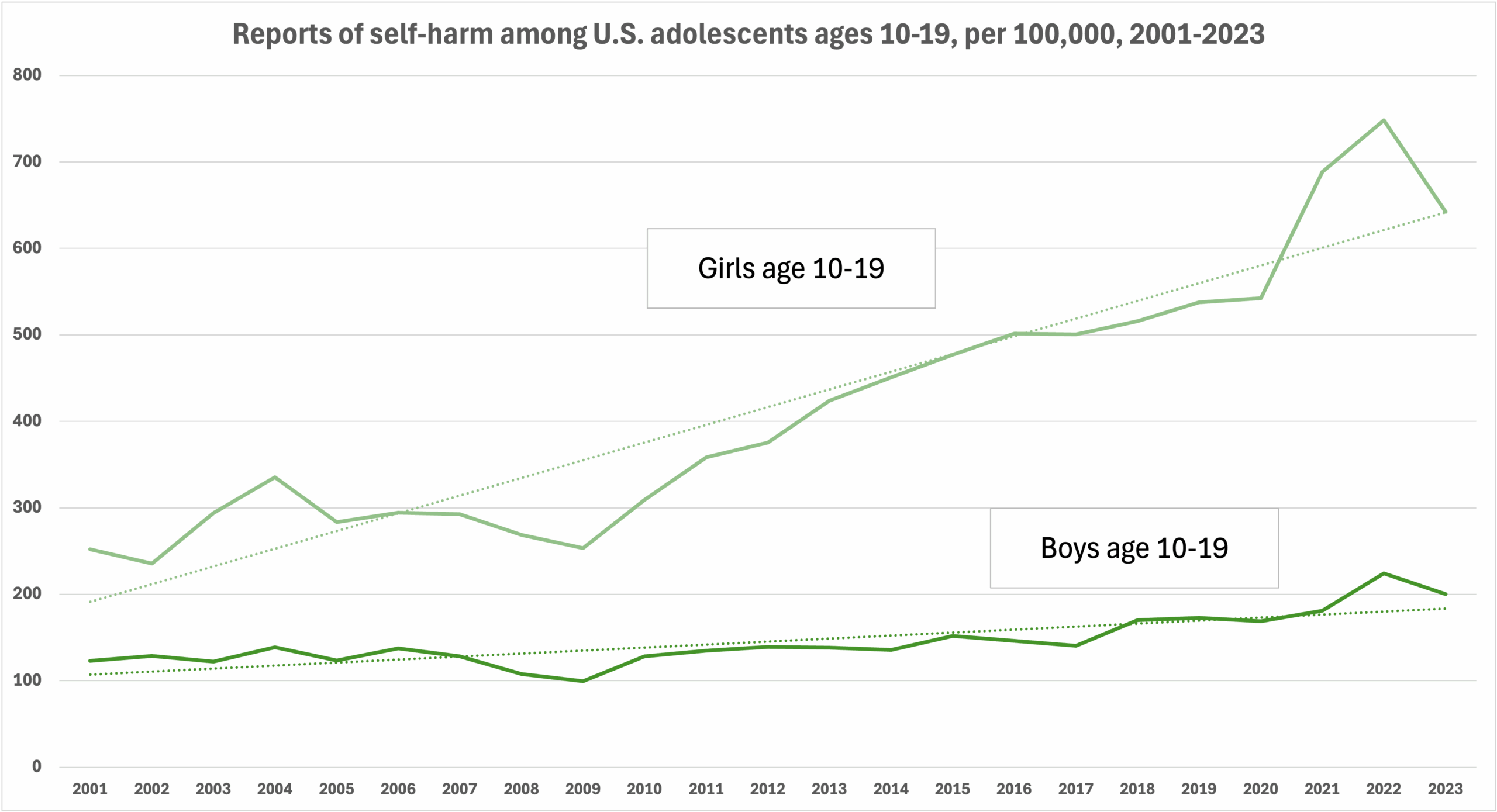

The reasons for this scarcity should be familiar by now. A large component of the problem is that more than half of mental healthcare service providers are over the age of 55 (Figure 3), but because of various bottlenecks in the training and licensing systems, not enough young people are moving into the field to make up for a future wave of retirements.

There is also a reluctance among new providers to move to rural areas for fear of not getting paid as much as in urban clinics. These are critical challenges that are well documented nationwide, and they are a part of the reason the rates of mental illness and suicide are higher in rural areas: rural people don’t have access to the services that can help them.

“We can provide suicide hotlines to farmers all day long, but that doesn’t address the root cause,” said Sam, a member of the Upper Sioux Community in southwestern Minnesota. (Given the sensitive nature of the topics, interviewees were given the option of using a pseudonym for this report.) Sam is a social researcher and land stewardship advocate who has worked with Minnesota farmers. “[A] suicide hotline is what you do during the crisis, but it’s not fixing any of the other issues that are actually going on that are causing it.”

While statewide outpatient statistics are not readily available, national evidence shows that rural residents face longer drives to outpatient clinics. The greater distance between communities and the sparse population of smaller towns create adverse economies of scale that increase the cost of providing services. This in turn has led to clinic closures and healthcare consolidation, further squeezing the supply of services over the years as healthcare companies try to keep revenue ahead of expenses. The closures also result in even longer drives to receive services.

Figure 3: Nearly 60% of Minnesota’s mental healthcare providers are over the age of 55. Data: MN Department of Health.

For inpatient mental health treatment, said Travis, an employee at a West Central Minnesota mental healthcare organization, “there’s a back and forth between hospitals and the crisis centers trying to be like, ‘Who’s got the open bed?’ And sometimes there’s not an open bed.” Open bed does not mean an actual physical bed, it means staff—having enough staff trained and licensed in the correct skills to treat patients effectively and safely.

Cost is, of course, a major issue. Whether people have health insurance through their employer, they buy it themselves, or they receive it through a public option, costs continue to rise, and so does the price of the insurance.[2]

“I can recognize when a kid is really struggling,” said Sylvia, a school administrator and social worker in Wilmar, but on more than one occasion, when she has recommended to a parent that their child be seen by a doctor for depression, the parent has replied, “Okay, but we don’t have health insurance.”

A lack of transportation or public transportation also limits people in rural areas,[3] who are more likely to not have their own vehicles or are unable to drive due to age, income, or disability even as the distances patients need to travel to get services continue to increase. According to a 2024 Minnesota Department of Health report on the state of rural healthcare, rural patients seeking inpatient mental health and chemical dependency treatment must travel three times farther than their urban counterparts.[4]

But while these challenges are tough for all rural families looking for help, they are even greater for people of color.

Rural Minnesota is becoming increasingly diverse. In 1980, people of color made up 2% of the state’s rural population, representing mostly Native American communities in northern Minnesota. By 2024, however, that number had increased to 14%, although people of color tend to be more concentrated in certain cities or counties around Greater Minnesota. For example, the two counties with the largest percentage of people of color in the state are Mahnomen at 55% and Nobles at 47% (Figure 4).[5]

Figure 4: Much of Greater Minnesota has seen significant changes in their demographics. Source: Center for Rural Policy & Development, “State of Rural Minnesota.”

Despite the growth in the BIPOC population, however, very little research has been conducted on their mental healthcare needs or how to help them access those services in Greater Minnesota. A study published in 1999 found that not only were mental health resources for communities of color simply not available, but there wasn’t enough data to analyze the issue. An updated study from 2020 found that little had changed.[6]

The challenges

People of color tend to have lower incomes, may not speak English or speak it well, or they simply don’t believe there is such a thing as mental illness and/or that anything can be done about it. These circumstances all make the standard rural barriers to help even higher.

Hovering over all of that, though, is an issue of trust. The history of healthcare in America is riddled with well-documented incidents of research that included everything from malaria studies on white prison inmates to radiation experiments on black cancer patients to the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments.

Consequently, many people of color, especially African Americans and Native Americans, see the healthcare system as simply a continuation of the systems that allowed these things to happen in the past.

A recent example of this legacy was seen during the pandemic in the disproportionately high rates of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in communities of color in the previous year, a 2021 article in the New England Journal of Medicine stated, attributing it to a distrust of COVID-19 vaccinations within BIPOC communities. The article went on to state that the hesitancy toward not just the vaccines but seeking healthcare in general during the pandemic was rooted in those past abuses, which “have established doubt and skepticism about the trustworthiness of science, research institutions, and government that are not easily overcome.”[7]

This same trust problem has become a significant barrier to mental healthcare access for communities of color.[8]

One aspect of this trust barrier that may be easiest to see and understand is the lack of licensed mental health care providers who are also people of color. Erik Sievers is the executive director of Hiawatha Valley Mental Health Center, which serves a population of about 160,000 in five rural counties in southeastern Minnesota. “We’re an agency of about a hundred or so. We have one provider who’s not a white person. One,” he said.

According to Sievers, around 6% of the region’s population are people of color. “It’s a very small percentage, but still, it’s a percentage, and I think we are grossly underserving that population… and it’s further compounded by the lack of providers who understand or reflect a culture that isn’t white and English-speaking….”

A common understanding of a community’s experiences and culture is important, especially when it comes to mental health. Steve, whose heritage is both African American and white, hears similar things from the students he works with at a local college. “Representation, I think, is what’s stopping a lot of students [from seeking help]. It’s hard to be able to connect with people that you don’t think will understand what you’ve experienced.”

A simple example of the differences among cultures can be seen in attitudes toward individualism and collectivism among America’s various ethnic and racial groups. Mental health professionals from Latin American, Asian, African, and Middle Eastern backgrounds understand from their own experiences that multigenerational households are quite normal in those cultures.[9] On the other hand, a mental health professional of northern European descent, a culture that emphasizes individualism, might see extended family and multiple generations living together in one home as not normal or even healthy.[10]

According to Gabriel, a long-time school social worker in rural West Central Minnesota, it’s important that school social workers build trust with students, but the trust part often only comes when students see social workers who share their racial or cultural background.

“As a person of color, you’re looking for someone you can relate to, someone that maybe can understand your culture, because a lot of times, you know, in smaller towns, you feel isolated,” he said.

But there are barriers for people who want to become licensed mental health providers also. Student loans and the prospect of low pay are significant deterrents that keep people from entering the field and may explain in part why only half of people who graduate with a degree that leads to a licensed mental healthcare provider role actually attain a license.[11] For people of color, it’s even harder.

Jessica Estrada is a mental health therapist practicing in Spicer, Minn. (population 1,081), while also pursuing her doctorate in social work. “It’s hard for anyone to go to college with so much debt…,” she said, “but it’s even harder for those like Hispanics and Somalis, who are already struggling financially, to even try to think of going to school to get more BIPOC providers out there.”

The licensing process has its issues, too. In 2022, the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB) reported that a test taker’s demographics are the strongest predictor of whether that social worker will pass the exam required to become a licensed mental healthcare professional.[12] While 80% of white female examinees passed the ASWB clinical exam, pass rates for other groups were not as good. [13]

Table 2: The passing rate for one of the standard licensing tests varies

dramatically based on a person’s race or ethnicity. Source: Association of Social Work Boards,

“2022 ASWB Exam Pass Rate Analysis.” (See footnote 13.)

“Some of the standardized licensing board exams create barriers,” said Sievers. “They’re written for white people to respond to…. Are there ways to evaluate a provider that are more universal, no matter what your culture is?”

The two major organizations in the social work world—the Association of Social Work Boards, which develops and administers the licensing exam, and the National Association of Social Workers, the nation’s largest professional membership organization for social workers—disagree on the cause of this racial discrepancy. Is it baked into the test or is it baked into the educational system? But they both agree that something is affecting the passing rates of test-takers based on race or ethnicity, said Dr. Paul Mackie, a professor at Minnesota State Mankato, a Licensed Independent Social Worker, and past president of the National Association for Rural Mental Health.

At the same time, however, it shouldn’t be assumed that any provider of color will be fine for any person of color. There can be a tendency to lump people who are not totally white into one broad category—“people of color”—instead of recognizing that that category is made up of countless groups, each one unique based on people’s experiences, culture and history. Just as many people prefer a doctor of the same sex because they feel that person will better understand “what I’m going through,” people of color would often prefer to see someone of their same ethnicity and/or background, especially for the very personal experience of mental health services.

“The problem of putting [BIPOC people] all together is that you don’t recognize that the Somali community has specific traumas, Latinos have different traumas, Karen have different traumas in history,” says Juan, a community leader in Willmar, originally from Peru. “Our journeys have been different.”

This is the case for Native Americans. “Native people from Upper Sioux aren’t going to seek out mental health resources that are not provided by Upper Sioux,” says Brooke, a Dakota tribal member, healthcare provider, artist, and activist. Although Native Americans have experienced racism like other BIPOC groups, their struggles generally and Upper Sioux’s specifically are not about race and racism so much as they are about self-determination and who has the right to make decisions for their people and their land. A person who is not Native American, even if they are a person of color, may not understand that this historic lack of control over their own destiny is in large part at the root of Native Americans’ struggles, including their mental health issues.

“So if I’m going to go see a person of color as a therapist,” says Brooke, “there’s a tendency [for that therapist] to categorize the indigenous experience as racial rather than as socio-political, which then is a whole other level of like, ‘Okay, now I get to educate you on this during therapy hours that I’m paying for? Great.’”

Stigma & fear

A major and common barrier to seeking care for symptoms of mental illness, regardless of race, is stigma. The entire subject of mental health and mental illness can be difficult to talk about, especially in communities where these concepts are seen as only relevant to “other people.”

“How do you go about [saying], ‘Hey, I need help!’ without feeling too shameful or that people are going to look at you differently?” says Taharqah, originally from Ethiopia.

Stigma and the fear of what others will think, especially those closest to you, may be the biggest deterrents to seeking help. In small rural towns where there is little anonymity, a person who is already feeling stressed and/or experiencing elevated symptoms of their mental illness might feel distrustful, fearful and suspicious, making them isolate further and even less likely to ask for help.

“In working with families of color, I think that’s one of the biggest things,” says Gabriel, the middle-school social worker. They feel isolated in a community where most people don’t look like them. “It’s kind of like, ‘I’m not gonna put myself out there to get hurt.’”

“The stigma of it is, I think, a big piece in our community,” says Steve, the community resource coordinator at a local college, about the fear around mental health services. “If I told my father that I was going to go see a therapist, he would laugh me out of the room, or ask me really messed-up questions like, ‘What kind of white s*** is that?’ They would think that you’re sending them to a therapist so they can have their mind read and their soul dragged out of them.”

Many of the people of color interviewed for this report said that there is a perception in their communities that mental illness does not exist in their culture, and, understandably, even the definition of “mental health” is not well understood.

Filsan, a Willmar resident, points out the urgent need for people in her Somali community to learn more about what mental health is, as well as how to identify the symptoms of mental illness. Because of stigma, people in her community don’t understand that mental health is a real thing, she said, “so how are our kids supposed to know what mental health is? They just think, ‘Oh, well, I have to deal with it because my parents do, too.’… Not talking about it is what’s making it worse.”

Language barriers are another major isolating factor. With mental healthcare, patients need to be able to accurately relate their thoughts, feelings, perceptions, and physical symptoms, but the many dialects of a language can become a problem. Miranda, a Spanish-language interpreter, found with one patient, “They were speaking Caribbean Spanish. That is not my Spanish.”

A Latina social service provider said of one of her clients, who was struggling after her son passed away, “My client told me ‘I really want to have a [support] group. I know that they have a group, but they all speak English.’”

A mental health administrator in southwest Minnesota explained that because of the shortage of interpreters, there’s also a high likelihood in small communities that the only person able to interpret for a client at a healthcare visit is also a member of that client’s family. When that’s the case, “you’re not going to seek out services. So, we deal with that a lot to make sure that family members are not involved.”

Medication is another common barrier. “The whole piece about medication that you hear is, ‘Well, I’m not putting my kids on meds,’” says Sylvia, the school social worker. The parents may have experience with a family member who was a drug user, and they fear their own child could become addicted. “It’s kind of unrealistically based sometimes, but it’s real to them,” she said.

Encounters with the law

In 2017, we reported that when a person suffering from severe symptoms of mental health experiences a crisis, 911 is often the first call. Although mobile crisis response teams are located around the state, the travel time can mean that law enforcement is the first on the scene and there is a good chance that the person will end up at either the hospital or in jail.[14]

For many BIPOC groups, the possibility of an encounter with law enforcement can raise considerable fear that seeking out help will draw attention, resulting in deportation, separation from family members, and other legal consequences.

For example, even though the people who answer the phones at the 988 suicide help line can’t tell a person’s identity or where they are calling from (unlike 911), because of past experiences over the decades, many people of color, especially Black Americans and Native Americans, are still reluctant to use it for fear of the police showing up at their door.

“In my community, there’s a 50% greater chance you’ll be charged with a crime for too many mental health calls to your home than actually receiving help,” said a Chisholm-based mental healthcare professional whose work includes providing services for Native American families in and around the Bois Forte Reservation.

“Who’s going to watch their kids?” said Sam from the Upper Sioux Community near Granite Falls. The act of engaging with the system can set many consequences in motion, “which then make you actively afraid to seek these things out. It cultivates a culture of fear and increased stigma, which I think is the opposite of the intended effect.”

Native Americans have their own long history of family separation and losing children to powers and systems they have no control over, and they are dependent on Western mental health treatment models that are “utterly devoid of cultural context,” said Brooke. Native communities need to develop their own mental healthcare services for their own healing, Sam and Brooke both emphasized.

Some Native American bands in Minnesota are doing that now. The Red Lake Nation in northwest Minnesota, for example, has reinvented their social services department using their own words, values and beliefs to make it better fit their needs. A 2022 article in MinnPost reported how instead of “clients,” the office now works with “relatives,” reflecting the band’s strong culture of family. Foster parents are known as “relative care community service providers,” and for a people who have experienced a long history of children being taken away from families, “child protection case management” is now called “reunification services.” The department itself has been renamed from Children and Family Services to Ombimindwaa Gidinawemaaganinaadog, which means “Uplifting All Our Relatives.” The new approach, Executive Director Cheri Goodwin explained, “focuses on keeping families together by looking at their strength and resiliency through a Native lens.”[15]

In 2015, the White Earth Reservation launched its own opioid addiction treatment program specifically for pregnant mothers.[16] The program seeks to support mothers, helping them manage their addiction with medication but just as importantly with the support of each other. Removing children from the homes of addicted parents and sending them to unrelated foster homes was the standard practice for social service programs working with Native Americans. In the years before the program’s start, “about 48 babies born to White Earth moms were taken away from their parents in the hospital and sent to foster care,” Julie Williams, a former substance abuse case manager, said in an article. Since the start of the MOMS program, there have been no more separations.

The people developing these programs are of the same cultural community and background as the people they are helping. By incorporating tradition and culture into the programs, they are creating not just a safe and familiar atmosphere, but also an atmosphere that says their culture is important and so are they.

Faith: A key part of rural life

Long before there were counselors and therapists for mental health, people consulted with their faith leaders when they felt something was wrong. Faith has a strong tradition in rural America, including among BIPOC communities, based on an understanding and belief that the spiritual aspect of a person’s makeup is very real and just as important as the physical. Whether it’s because of faith or simply the lack of anyone else they feel they can trust, people often go to their religious leader first.

It’s natural for a person to seek help from their pastor or faith leader, says Jonathan Stadler, Ph.D., a professor and chair of the psychology department at Bethany Lutheran College in Mankato, MN, because “that relationship is already there, and they are likely to think there’s a spiritual component to it.”

In some communities, religion is considered enough to address mental health problems. In the Karen community, says Smile, a Karen immigrant, entrepreneur, and language interpreter, “most Karen people, since they believe in a God, are going to show you that the therapy they’re going to [use] is ‘We should pray to God, worship God.’ So, we don’t have to worry about a thing out here, you know? So that helps. From what I know, not a lot of Karen people are depressed and stressed. I mean, they have stress but not a lot of depression. It’s a good thing, because the way they handle depression is first, they put God, and then second, their family.”

It’s somewhat similar in Filsan’s Somali culture. “In terms of dealing with stress or depression, we’re supposed to pray about it and read the Quran.” That will work, she says, “but then you need to talk about what’s bothering you inside, too.”

Mental illness definitely has biological and social or societal components to it, says Stadler.

“For instance, we wouldn’t just say to someone who’s suffering from diabetes to pray harder,” he said. “Absolutely, we should rely on God, but God gives us a lot of blessings for taking care of ourselves, including a right understanding of the psychological and biological factors that could be impacting one’s mental health.”

Bridging those barriers: How to expand access

Recognize the importance of programming developed by the people it’s intended to help

When it comes to developing mental wellness programs for people of color, our interviewees emphasized that incorporating a group’s heritage and culture into programs is crucial, and the initiatives need to be designed and delivered by the cultural communities they are intended to serve, as the Red Lake and White Earth nations’ programs did.

Research from the National Institutes of Health on suicide prevention programs for Indigenous people, for example, found that initiatives that were developed with and by the community, drawing on local culture, knowledge, need and priorities, had “substantial [positive] impact on suicide-related outcomes.…”[17]

And it doesn’t even need to be all that formal. Sam, for instance, has a colleague who organizes foraging walks, canoe paddling excursions, and other nature-based activities. “These are mental health services that he’s providing. He’s not a licensed therapist—he works for an insurance company. But he’s getting people out on the land, getting them out on the rivers, connecting them to one another.”

Crossing state lines

So far, 39 states are embarking on a major experiment in expanding access to mental health services. The Counseling Compact (counselingcompact.gov) is an agreement among states that will allow mental health providers to see people in not just their own states but in the other member states. Minnesota and Arizona are the first two states to complete the technical and regulatory work. Right now, only licensed professional counselors and licensed professional clinical counselors are allowed to apply for privileges to practice in each other’s states, but work continues to expand to many other counseling roles.[18] The state legislature plays a major role by approving policies and regulatory changes that make the compact possible.

Mentors for students

Being mentored by a professional with a similar background is vital for career development in the mental healthcare field, said Estrada, the mental health therapist and doctoral candidate from Spicer. “The lack of a strong support network in rural areas can be particularly isolating for people of color.”

Estrada was paired up with a BIPOC supervisor through the National Association of Social Workers, but the funding for that program is limited, “so it’s not everyone that gets it. I’m just lucky I got it…. Finding a mentor who understands the unique challenges of being a person of color in the mental health field can be difficult. Aspiring clinicians of color may feel they need to navigate the professional world alone, which can be discouraging and contribute to burn out.”

Licensure reform

The unbalanced passing rates for standardized licensing tests have not gone unnoticed among those who write the tests, and they are now encouraging social work licensure reform.[19] Some of the recommendations:

- Include more input from mental health providers of color in the development of standardized tests.[20]

- Replace standardized multiple-choice exams with alternatives like competency-based evaluations, portfolios, or supervised practice assessments. [21]

- Reduce cost and structural barriers. For example, remove retake waiting periods; provide free and low–cost test preparation resources; lower or remove exam fees; and offer language accommodations, including ESL support.[22]

In 2024, Minnesota passed legislation that would give people in groups that have traditionally had difficulty with the licensure test a pathway around the test. [23] Based on a successful pilot program with Hmong immigrants and others for whom English is a second language, licensing candidates now have the option to either take the traditional exam or complete additional supervision hours to receive their license.

Michigan is also working on the exam issue. The Michigan branch of the National Association of Social Workers, for example, is supporting a bill in the Michigan state legislature that would overhaul the state’s licensing requirements to make it easier for individuals to get and keep their license. Among other things, the bill would:

- Restructure licenses to better align with licensing standards in other states.

- Replace the ASWB exam requirement with a more affordable, open-book, state-specific & competency-based exam.

- Reduce the required clinical supervision hours from 4,000 to 3,000. Michigan’s current requirement is the highest in the nation.[24]

Direct-Entry Mental Health Practitioners

During her three years as Chief Impact Officer at Woodland Centers, a mental healthcare organization serving seven counties in West Central Minnesota, Kim Madsen has dealt with barriers and worked on bridges to better mental healthcare in the communities they serve.

She recommends allowing mental healthcare providers to get more on-the-job training as a supplement to or even replacement for academic education. This direct-entry model would allow for faster expansion of the mental healthcare workforce.

“What’s really needed is what you have seen with, for example, plumbers and electricians, where [employers] hire them, and there’s a [training] process, right? So you’re a journeyman for two years, and then you get to move up. We need to figure out a system of education where people can come into the field directly in some capacity…. We would do it in a heartbeat if there was money.”

The “money” has to do with supervised hours. One thing that is often not mentioned is that to become licensed, a graduate must obtain a certain number of hours where they see clients while supervised by a licensed provider. Those hours cost the host clinic money, as was discussed in the Center’s 2023 report on the mental health workforce shortage. “Clinicians are reimbursed (paid) by the insurance company, Medicaid, Medicare, or another payer for their time spent seeing clients, but not so when they are supervising interns.”[25] As a result, the clinic either can’t afford to supervise students, but hosting a student is one of the most effective ways to attract—and keep—a student to a rural clinic.

Telehealth

Telehealth can especially help rural people of color access appropriate, effective mental healthcare, says Terica Toliver, Senior Director of Clinical Therapy at Louisiana-based Iris Telehealth, which provides therapy via telehealth through her contract with ElevaCare in Southwest Minnesota. Telehealth gives people of color a broader range of providers to choose from, including providers who share the same racial and cultural backgrounds.

It’s not a perfect solution, however. Hundreds of thousands of Minnesotans don’t have access to the broadband internet service required for telehealth to work reliably,[26] and telehealth isn’t for everyone. Some patients simply don’t feel comfortable talking to a stranger about their mental health on a digital screen.

Peer Support

Peer support, which has its roots in the 1970s, is another form of support gaining momentum in the last few years. Peer support connects trained peer mentors—individuals who have experienced mental illness and recovery themselves—with community members who need support. According to a 2024 article in Psychiatry Advisor, while peer support has about the same level of effectiveness as clinical practice on outcomes like preventing rehospitalization and relapse, peer support scores better in areas related to the recovery process, or how a person gets along after treatment, especially in areas like feelings of empowerment and engagement.[27] The benefit comes from the connectedness with people who understand what clients are going through.

Teaming up with first responders

There is a growing movement nationwide toward greater collaboration between first responders (police, firefighters, emergency medical services, etc.) and social workers experienced in working with people with mental health issues. Motivated by a number of dynamics, including the rising number of 911 calls related to mental health crises and the limits of traditional police training, programs like these increase the likelihood that citizens receive appropriate medical care while leading to fewer arrests and less use of force.[28]

Ashley Kjos is Chief Executive Officer of Woodland Centers. “I would love it if every law enforcement officer had a mental health professional riding with them. It’s not a scary thing, it’s just, ‘Hey, let’s just do a ride.’” When Kjos did a ride-along to learn more about policing, the second call was a death by suicide. Once the scene was cleared, Kjos was able to bring in their mobile crisis team to talk with the family. “We said, ‘Yes, let’s get your team here. Let’s [all] work on this.’”

The current challenges to putting together team-ups like this include the need for training and funding, as well as the ongoing debate over the risks and benefits of having armed officers present in a mental health crisis situation.[29] Despite this, team-ups like these, called “co-responder teams,” are already active in communities like St. Paul[30]; Denver[31]; Eugene, OR[32]; Albuquerque[33]; and Cleveland, OH.[34]

More and Better Mental Health Support in Schools

Pete, one of our interviewees and a recent high-school graduate, is acutely aware of the need for both better mental health support and mental health education in high schools. Pete lost a close friend, a 17-year-old Somali youth, to suicide in 2024. Now he advocates for mental wellness education in all of Minnesota’s high schools.

He feels optimistic despite the challenges many rural communities face when it comes to a lack of mental health services. He says he definitely sees “an uptick in people organizing things [at school], and that’s really cool. I feel that we are waking up to these problems and addressing them and having more conversations…. I want to have my career be rooted in helping people wake up.”

* * *

Because of the amount of time it takes to pass legislation that will change policy, approve funding, and move students from start to licensed in today’s system, most of the above ideas will take time. Fortunately, where rural communities lack formal resources, they do have a substantial capacity for informal resources: people helping each other out.

Let’s talk

Soon after George Floyd was killed in South Minneapolis in 2020, Dr. Remi Douah, a Minneapolis-based public health researcher, created an impromptu outdoor therapist’s office on the street, free of charge. He began bringing two chairs to a green space nearby, a memorial dedicated to black people who had died while in police custody, he explained in a 2021 US News & World Report article. “I was seeing people coming to this place, all shattered. And they wanted to talk to someone, and I was there….”[35] Soon, he needed more chairs. Since then, he and his son have co-founded the non-profit organization 846s (www.846s.org), which focuses on mental wellness education through youth workforce training, wellness workshops, and peer support groups.

While Dr. Douah is in Minneapolis and has a degree, residents of rural communities are quite capable of doing something similar: providing a place where people feel like they can talk about “things” and don’t have to feel alone. The impact of isolation and loneliness on mental health is well researched and well documented, especially since the pandemic. [36] Isolation can be difficult for a mentally healthy person; for a person struggling with mental health symptoms, it can make things worse. This is why Robert Putnam, the author who brought loneliness to public attention in his 2000 book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, said in a 2024 interview, “Loneliness. It’s bad for your health, but it’s also bad for the health of the people around you.”[37]

This is where we see the importance of coffee shops and diners where people can get together informally; book clubs; religious study groups; and in men’s sheds,[38] a movement based on the principle that men talk about things in ways that are different from women. Notice that these are informal settings where the activity isn’t technically about mental health, but they are all opportunities to simply talk. To help with these conversations, a collaboration between the University of Minnesota Extension and the Minnesota Department of Agriculture offers COMET, a program that teaches average people how to ask their loved ones, “How are you doing?”[39]

Getting coordinated, keeping it fun

A common problem for many rural communities is that while they have some help for people dealing with mental illness or activities around creating mental wellness, the help is not comprehensive or coordinated with other efforts, and getting the word out about services or even the importance of talking about mental health is difficult.

To address this in the Willmar area, Woodland Centers collaborated with other organizations in 2023 to launch Kids Connection, a weekly gathering for families at the mall. One day a week, for a few hours after school, the local mall hosts activities for the kids while the adults learn about mental healthcare resources available in the community. The event attracts a diverse cross-section of this very diverse community.

Reconnecting kids with their heritage

Gabriel, the school counselor, uses the power of activities that build resilience by leading a multicultural club at his district’s middle school. He also brings his students to St. Cloud State University to experience the cultural celebration put on there by the university’s international students every other weekend, where “…they get to experience the culture of others and eat the food,” he said. These cultural activities are important, according to Gabriel, because they tell his students parts of their own stories that they are not necessarily hearing elsewhere. “I think a lot of the kids I work with don’t know their background. They don’t know their history…. What [they] see on TV, the evening news, is not always positive or representative of their community.” Seeing other people from the countries they or their ancestors came from teaches them about their own culture’s story—the positive attributes, the strengths, the accomplishments, in turn helping their overall mental wellness, Gabriel said.

Changing how we think about how people use spaces

There are many opportunities for “informal therapy” in rural places, but to create these spaces, we may need to change the way we think about how people use spaces.

Nearly every person interviewed mentioned the need for gathering spaces where people feel safe and welcome, but as rural populations shrink, towns have lost many of the traditional places where non-structured, informal gatherings were easy—local diners, coffee shops, churches, and bars.

Even in towns where these places do still exist, people of color may not feel welcome, so they create their own spaces. New immigrants often gather regularly at local parks and on small-town street corners where they can speak in their native languages, share stories, eat together, and play sports, all important to their well-being.

These outdoor gatherings aren’t as easy during a Minnesota winter, but like immigrant groups that came before them, newer immigrants are working to create more gathering spaces. While these spaces will look and feel different depending on each community’s needs, they all foster togetherness.

Even the most casual get-togethers and cultural activities strengthen mental wellness, says Miranda, the interpreter. Participating in activities like community gardening, Mexican folk dancing, and loteria, a traditional Mexican card game, can help people’s mental wellness by connecting them with each other and with their cultural heritage.

In conclusion

So many of the challenges creating barriers to mental health resources affect all rural Minnesotans. The lack of service providers, the distance people must travel, the stigma and fear around even talking about mental health, plus other negative social determinants like chronic poverty and substance abuse, can all compound, influencing a person’s health and mental health even more than healthcare access or lifestyle choices.[40]

And yet, there is still very little research on the mental healthcare needs of communities of color in rural Minnesota or in other rural areas of the U.S. The characteristics of rural BIPOC communities can vary quite a bit around the country, but when it comes to accessing mental healthcare and healthcare in general, they all share the unique combination of the barriers impacting rural residents and barriers impacting people of color. More research is needed into just what that intersection means.

And then, of course, research requires action to go with it. As discussed, there are several ways that people of color and their communities are tackling these issues themselves. Here’s a summary.

Make it okay to talk about mental health. Stigma and the fear it creates is epidemic in both white and BIPOC communities, keeping people from seeking help. Getting the message out that it’s okay to talk about mental health will help.

Get information out there. Information transfers more slowly in rural areas, and BIPOC communities can be disconnected from regular channels. We can encourage better communication on what’s working in different communities and among different ethnic groups.

Informal help. Isolation is the enemy of good mental health. Figuring out ways to get people together to talk about what’s bothering them or to even just have a good time may be the most important solution of all.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to each interviewee who shared their insights and experience with us. We are also grateful to the following people for their advice and encouragement: Dr. Ronald Ferguson, Thad Shunkweiler, and Dr. Remi Douah. Finally, heartfelt thanks to research assistants John Rodriguez and Tess Hessin for their hard work and attention to detail.

About the author

Mitra Milani Engan is an independent researcher and writer who has spent the past 30 years studying the role of culture in human interactions. Her current work explores how cultural factors influence access to mental healthcare in rural Minnesota, bridging social understanding with community wellbeing.

References

“2022 ASWB Exam Pass Rate Analysis.” Association of Social Work Boards, August 2022. https://www.aswb.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/2022-ASWB-Exam-Pass-Rate-Analysis.pdf

Abrams, Abigail. “Black, Disabled People at Higher Risk in Police Encounters.” Time, June 25, 2020. https://time.com/5857438/police-violence-black-disabled/

Alang, Sirry. “Are There Disparities in Causes of Perceived Unmet Need for Mental Health Care?” Conference Papers – American Sociological Association, January 2014, 1–17.

Allard, Sam. “Cuyahoga County Eastern Suburbs to Collaborate on Crisis Response.” Axios Cleveland, May 8, 2024. https://www.axios.com/local/cleveland/2024/05/08/cuyahoga-county-eastern-suburbs-collaborate-crisis-response-first-call

“Alternative Transit Approaches for Rural Communities.” Crossroads, August 9, 2023. https://mntransportationresearch.org/2023/08/10/alternative-transit-approaches-for-rural-communities/

“Barriers to Transportation in Rural Areas – RHIhub Toolkit.” Rural Health Information Hub. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/transportation/1/barriers

Bloxom, Quincy, and Brandi Anderson. “Deconstructing Social Work Exam Bias: Advocacy Practice Guidelines to Close the Gap.” Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work 21, no. 2 (November 9, 2023): 236–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2023.2278691

“BIPOC Mental Health: Barriers and Ways to Support.” Lyra Health, June 30, 2023. https://www.lyrahealth.com/blog/bipoc-mental-health/

Brann, Melina. “Social Work Licensure Modernization Act Introduced!” National Association of Social Workers–Michigan Chapter, October 19, 2023. https://www.nasw-michigan.org/news/655628/Social-Work-Licensure-Modernization-Act-Introduced.htm

Carney, Courtney J. Jones. “The Role of Experimentation and Medical Mistrust in COVID-19 Vaccine Skepticism.” The Elm, January 24, 2021. https://elm.umaryland.edu/voices-and-opinions/Voices–Opinions-Content/The-Role-of-Experimentation-and-Medical-Mistrust-in-COVID-19-Vaccine-Skepticism-.php

Cooper, Samantha, ed. “Mental Health Care Stigma in Black Communities.” Counseling Today, February 28, 2023. https://ct.counseling.org/2023/02/mental-health-care-stigma-in-black-communities/

Davies, Nicola. “Exploring the Value of Peer Support for Mental Health.” Psychiatry Advisor, May 20, 2024. https://www.psychiatryadvisor.com/features/exploring-the-value-of-peer-support-for-mental-health/

DeCarlo, Matthew P. “Racial Bias and ASWB Exams: A Failure of Data Equity.” Research on Social Work Practice 32, no. 3 (December 2, 2021): 255–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497315211055986

Division of Health Policy. “Rural Health Care in Minnesota: Data Highlights, Nov 2023.” Minnesota Department of Health, November 16, 2023. https://www.health.state.mn.us/facilities/ruralhealth/docs/summaries/rhcmn.pdf

Division of Health Policy. “Rural Health Care in Minnesota: Data Highlights, Nov 2024.” Minnesota Department of Health, 2024. https://www.health.state.mn.us/facilities/ruralhealth/docs/summaries/rhcmn.pdf

Eldred, Sheila Mulrooney. “Native-Led Program Rewrites the Rules for Moms’ Opioid Recovery.” The Imprint, November 21, 2024. https://imprintnews.org/top-stories/a-native-led-program-on-the-white-earth-reservation-is-rewriting-the-rules-on-opioid-treatment-for-parents-its-working/256144

“Ensuring Health across Rural Minnesota in 2030.” National Rural Health Resource Center, November 2020. https://www.ruralcenter.org/resources/ensuring-health-across-rural-minnesota-2030

Esserman, Dean. “Co-Responder Models in Policing: Better Serving Communities.” National Policing Institute, August 27, 2021. https://www.policinginstitute.org/onpolicing/co-responder-models-in-policing-better-serving-communities/

Fuhrman, Emma, Teia Kopari, Cody Reinke, and Josie Schultz. “Investing in a Culturally Diverse Mental Health Workforce in Minnesota. Issue brief.” Minnesota State University Mankato, April 2021. https://ahn.mnsu.edu/globalassets/college-of-allied-health-and-nursing/social-work/pdfs/diverse-mh-workforce.final4.5.21.pdf

Garcia, Sandra E. “Where Did BIPOC Come From?” The New York Times, June 15, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/article/what-is-bipoc.html

Harless, Lavina. “Licensure: The Future of the Social Work Licensing Exams.” Social Work Today, 2024. https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/Spring24p32.shtml

Hay, Andrew. “New Mexico Mental Health First Responders Are Increasingly Civilians, Not Police.” Reuters, April 16, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/new-mexico-mental-health-first-responders-are-increasingly-civilians-not-police-2024-04-06/

Hernandez, Esteban L. “What’s Next for the Police Response Alternative STAR as It Turns Five.” Axios Denver, June 9, 2025. https://www.axios.com/local/denver/2025/06/09/whats-next-police-response-alternative-star

“Karen History.” Karen Organization of Minnesota, February 8, 2021. https://mnkaren.org/history-culture/karen-history/

“Licensure Modernization Hub.” National Association of Social Workers–Michigan Chapter. Accessed June 15, 2025. https://www.nasw-michigan.org/page/miswlicensureupdates

Louwagie, Pam. “Surroundings Make Racial Reckoning Look Different in Rural Minn.” Minnesota Star Tribune, December 5, 2020. https://www.startribune.com/surroundings-make-racial-reckoning-look-different-in-rural-minn/573305361/

Marill, Michelle Cohen. “Beyond Twelve Steps, Peer-Supported Mental Health Care.” Health Affairs, June 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00503

“Mental Health.” World Health Organization. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_1

“Mental Health Care in BIPOC Communities – Closing the Gap.” United Brain Association, June 30, 2022. https://unitedbrainassociation.org/2021/07/09/mental-health-care-in-bipoc-communities-closing-the-gap/

“Mental Wellness.” Global Wellness Institute, June 26, 2024. https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/what-is-wellness/mental-wellness/

McGuire, Thomas G., and Jeanne Miranda. “New Evidence Regarding Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health: Policy Implications.” Health Affairs 27, no. 2 (March 2008): 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393

Minot, David. “Mental Health in BIPOC Communities: How to Reduce Stigma and Barriers.” Behavioral Health News, April 19, 2023. https://behavioralhealthnews.org/mental-health-in-bipoc-communities-how-to-reduce-stigma-and-barriers/

“NASW-IA ASWB Test Disparities Response.” National Association of Social Workers–Iowa Chapter. Accessed June 15, 2025. https://naswia.socialworkers.org/Professional-Development/Iowa-Professional-Issues/NASW-IA-ASWB-Test-Disparities-Response

National Alliance on Mental Illness. “Guest Commentary: Representation Matters – Culturally Affirming Mental Health Care for Black Communities.” Austin Daily Herald, February 2, 2024. https://www.austindailyherald.com/2024/02/guest-commentary-representation-matters-culturally-affirming-mental-health-care-for-black-communities/

Onque, Renée. “Why Therapists of Color Are Leaving the Profession.” CNBC, September 28, 2022. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/09/28/heres-why-therapists-of-color-are-leaving-the-profession.html

“Office of Broadband Development Annual Report 2023.” Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development, January 15, 2024. https://mn.gov/deed/assets/2023-office-broadband-annual-report_tcm1045-606701.pdf

PeopleGroups.org. Accessed November 3, 2024. http://PeopleGroups.org/

Perzichilli, Tahmi. “The Historical Roots of Racial Disparities in the Mental Health System.” Counseling Today, July 18, 2022. https://ct.counseling.org/2020/05/the-historical-roots-of-racial-disparities-in-the-mental-health-system/

Plotts, Joseph. “Reducing Mental Health Stigma in Rural Minnesota.” MinnPost, August 28, 2023. https://www.minnpost.com/threesixty-journalism/2023/08/reducing-mental-health-stigma-in-rural-minnesota/

Poindexter, Morgan, Julea Shaw, Aarthi Sekar, Rowan Boswell, Caitlin French, and Jordan Varney. “Guest Commentary: Toward a New Model of Policing for Davis.” Davis Vanguard, September 1, 2020. https://davisvanguard.org/2020/09/guest-commentary-toward-a-new-model-of-policing-for-davis/

Quinn, Sandra C., and Michele P. Andrasik. “Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy in BIPOC Communities — Toward Trustworthiness, Partnership, and Reciprocity.” The New England Journal of Medicine, March 31, 2021. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2103104

Rep. Equity of Care: A Toolkit for Eliminating Health Care Disparities. American Hospital Association, January 2015. http://www.hpoe.org/Reports-HPOE/equity-of-care-toolkit.pdf

Ricciardelli, Lauren, Stephen Vandiver McGarity, Mbita Mbao, Kristen Erbetta, Joseph Herzog, and Matthew Knierem. “Racial Disparity in Social Work Professional Licensure Exam Pass Rates: Examining Institutional Characteristics and State Licensure Policy as Predictors.” Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work 21, no. 2 (November 24, 2023): 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2023.2285887

Seewer, John, Holbrook Mohr, Jennifer McDermott, Jeff Martin, Ryan J. Foley, and Reese Dunklin. “Why Did More than 1,000 People Die after Police Subdued Them with Force That Isn’t Meant to Kill?” AP News, June 3, 2024. https://apnews.com/article/associated-press-investigation-deaths-police-encounters-02881a2bd3fbeb1fc31af9208bb0e310

Shmerling, Robert H. “Is Our Healthcare System Broken?” Harvard Health Publishing, July 13, 2021. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/is-our-healthcare-system-broken-202107132542

Sjoblom, Erynne, Winta Ghidei, Marya Leslie, Ashton James, Reagan Bartel, Sandra Campbell, and Stephanie Montesanti. “Centering Indigenous Knowledge in Suicide Prevention: A Critical Scoping Review.” BMC Public Health, December 19, 2022. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9761945/

Smith, Kylie M. “How Bigotry Created a Black Mental Health Crisis.” The Washington Post, July 29, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/07/29/how-bigotry-created-black-mental-health-crisis/

“Social Determinants of Health.” World Health Organization. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

Staff, NASW-IL. “ASWB First-Time Pass Results Released: This Is Not OK.” National Association of Social Workers, August 8, 2022. https://www.naswil.org/post/aswb-first-time-pass-results-released-this-is-not-ok

Steiner, Andy. “Red Lake Nation Recognized for ‘Decolonized’ Approach to Child and Family Services.” MinnPost, February 6, 2024. https://www.minnpost.com/greater-minnesota/2022/01/red-lake-nation-recognized-for-decolonized-approach-to-child-and-family-services/

Sue, Derald Wing, David Sue, Helen A. Neville, and Laura Smith. Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory and Practice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2022.

Thomas, Marilyn D., Nicholas P. Jewell, and Amani M. Allen. “Black and Unarmed: Statistical Interaction between Age, Perceived Mental Illness, and Geographic Region among Males Fatally Shot by Police Using Case-Only Design.” Annals of Epidemiology 53 (January 2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.08.014

Triandis, Harry C. Individualism and Collectivism. New York, NY: Routledge, 1995.

Wade, Patrick. “New Academy Trains Social Workers and Police Officers Together.” Public Safety, July 15, 2022. https://police.illinois.edu/new-academy-trains-social-workers-and-police-officers-together/

Wendt, Dennis C., William E. Hartmann, James Allen, Jacob A. Burack, Billy Charles, Elizabeth J. D’Amico, Colleen A. Dell, et al. “Substance Use Research with Indigenous Communities: Exploring and Extending Foundational Principles of Community Psychology.” American Journal of Community Psychology 64, no. 1–2 (2019): 146–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12363

Weniger, Deanna. “As Law Enforcement Embeds Social Workers, Police See Positives, But Training Needed.” Police1, November 26, 2021. https://www.police1.com/mental-health-outreach/articles/as-law-enforcement-embeds-social-workers-police-see-positives-but-training-needed-0A22fZGKRh1hvCMK/

Werner, Marnie. “Identifying Bottlenecks and Roadblocks in the Rural Mental Health Career Pipeline.” Center for Rural Policy and Development, February 22, 2023. https://www.ruralmn.org/identifying-bottlenecks-and-roadblocks-in-the-rural-mental-health-career-pipeline/

White, Ruth. “Why Mental Health Care Is Stigmatized in Black Communities.” USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, February 12, 2019. https://dworakpeck.usc.edu/news/why-mental-health-care-stigmatized-black-communities

Williams, Monnica T., Alan K. Davis, Yitong Xin, Nathan D. Sepeda, Pamela Colón Grigas, Sinead Sinnott, and Angela M. Haeny. “People of Color in North America Report Improvements in Racial Trauma and Mental Health Symptoms Following Psychedelic Experiences.” Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy 28, no. 3 (December 10, 2020): 215–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2020.1854688

Williams, Joseph P. “After Police Reform Defeat, Minneapolis Residents Still Seek Change.” U.S. News & World Report, December 2, 2021. https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2021-12-02/after-police-reform-defeat-minneapolis-residents-still-seek-change

Zielinski, Sarah. “Henrietta Lacks’ ‘Immortal’ Cells.” Smithsonian Magazine, January 22, 2010. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/henrietta-lacks-immortal-cells-6421299/

Footnotes

[1] Werner, Shunkweiler, Rutherford Self, “Identifying bottlenecks and roadblocks in the rural mental health career pipeline,” Center for Rural Policy & Development, February 2023. https://www.ruralmn.org/identifying-bottlenecks-and-roadblocks-in-the-rural-mental-health-career-pipeline/; Marnie Werner, “Youth mental health: Where rural families can find help now,” September 2024. https://www.ruralmn.org/youth-mental-health-where-rural-families-can-find-help-now/

[2] Snowbeck, Christopher, “Health insurers propose hiking Minnesota prices between 9% and 26%,” Minnesota Star Tribune, June 17, 2025. https://www.startribune.com/health-insurers-propose-hiking-minnesota-prices-at-least-14-next-year/601372365

[3] “Alternative Transit Approaches for Rural Communities,” Crossroads, August 9, 2023, https://mntransportationresearch.org/2023/08/10/alternative-transit-approaches-for-rural-communities/.

[4] Division of Health Policy, “Rural Health Care in Minnesota: Data Highlights, Nov 2024,” Minnesota Department of Health, 2024, https://www.health.state.mn.us/facilities/ruralhealth/docs/summaries/rhcmn.pdf.

[5] “Rural of Minnesota Atlas,” Center for Rural Policy & Development, https://center-for-rural-policy.shinyapps.io/Atlas_2025/

[6] “Mental Health Care in BIPOC Communities: Closing the Gap.” United Brain Association, June 30, 2022. https://unitedbrainassociation.org/2021/07/09/mental-health-care-in-bipoc-communities-closing-the-gap/.

[7] Quinn, et al. Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy in BIPOC Communities — Toward Trustworthiness, Partnership, and Reciprocity | New England Journal of Medicine, March 31, 2021. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2103104

[8] Kylie M. Smith, “How Bigotry Created a Black Mental Health Crisis,” Washington Post, July 29, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/07/29/how-bigotry-created-black-mental-health-crisis/; Tahmi Perzichilli, “The Historical Roots of Racial Disparities in the Mental Health System,” Counseling Today, July 18, 2022, https://ct.counseling.org/2020/05/the-historical-roots-of-racial-disparities-in-the-mental-health-system/.

[9] Harry C. Triandis, Individualism and Collectivism (New York, NY: Routledge, 1995).

[10] Derald Wing Sue et al., Counseling the Culturally Diverse: Theory and Practice (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2022).

[11] Kammer, et al. “Unfinished Business: Examining Barriers to Obtaining Mental Health Licensure Among Minnesota Graduates: Findings and Recommendations,” a research collaboration between the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Minnesota Center for Rural Behavioral Health at Minnesota State Mankato and the Wilder Foundation, 2025. https://www.wilder.org/wilder_research/unfinished-business-examining-barriers-to-obtaining-mental-health-licensure-among-minnesota-graduates-findings-and-recommendations/

[12]Ricciardelli, Lauren, Stephen Vandiver McGarity, Mbita Mbao, Kristen Erbetta, Joseph Herzog, and Matthew Knierem. “Racial Disparity in Social Work Professional Licensure Exam Pass Rates: Examining Institutional Characteristics and State Licensure Policy as Predictors.” Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work 21, no. 2 (November 24, 2023): 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2023.2285887

[13]“2022 ASWB Exam Pass Rate Analysis,” Association of Social Work Boards, August 2022, p. 73. https://www.aswb.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/2022-ASWB-Exam-Pass-Rate-Analysis.pdf.

[14] Werner, Marnie, “Mental health services in Greater Minnesota,” Center for Rural Policy & Development, May 2017. https://www.ruralmn.org/mental-health-services-in-greater-minnesota/

[15] Andy Steiner, “Red Lake Nation recognized for ‘decolonized’ approach to child and family services,” MinnPost, Jan. 24, 2022. https://www.minnpost.com/greater-minnesota/2022/01/red-lake-nation-recognized-for-decolonized-approach-to-child-and-family-services/

[16] Sheila Mulrooney Eldred, “A Native-led Program on the White Earth Reservation is Rewriting the Rules on Opioid Treatment for Parents. It’s Working.” The Imprint, 11/19/2024. https://imprintnews.org/top-stories/a-native-led-program-on-the-white-earth-reservation-is-rewriting-the-rules-on-opioid-treatment-for-parents-its-working/256144

[17] Erynne Sjoblom et al., “Centering Indigenous Knowledge in Suicide Prevention: A Critical Scoping Review,” BMC public health, December 19, 2022, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9761945/.

[18] https://counselingcompact.gov/

[19] Matthew P. DeCarlo, “Racial Bias and ASWB Exams: A Failure of Data Equity,” Research on Social Work Practice 32, no. 3 (December 2, 2021): 255–58, https://doi.org/10.1177/10497315211055986; NASW-IL Staff, “ASWB First-Time Pass Results Released: This Is Not Ok,” NASW, August 8, 2022, https://www.naswil.org/post/aswb-first-time-pass-results-released-this-is-not-ok; “Beyond Data: A Call to Action,” Association of Social Work Boards, August 30, 2022, https://www.aswb.org/beyond-data-a-call-to-action/.

[20]Renée Onque, “Why Therapists of Color Are Leaving the Profession,” CNBC, 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/09/28/heres-why-therapists-of-color-are-leaving-the-profession.html.

[21]Lavina Harless, “Licensure: The Future of the Social Work Licensing Exams,” Social Work Today, 2024, https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/Spring24p32.shtml; “Licensure Modernization Hub,” National Association of Social Workers-Michigan Chapter, accessed June 15, 2025, https://www.nasw-michigan.org/page/miswlicensureupdates.

[22]Melina Brann, “Social Work Licensure Modernization Act Introduced!,” National Association of Social Workers-Michigan Chapter, October 19, 2023, https://www.nasw-michigan.org/news/655628/Social-Work-Licensure-Modernization-Act-Introduced.htm.

[23] Minnesota Board of Social Work, “Apply for Provisional License,” https://mn.gov/boards/social-work/applicants/applyforprovisional/

[24] National Association of Social Workers, Michigan branch, https://www.nasw-michigan.org/page/miswlicensureupdates.

[25] Werner, Shunkweiler, Rutherford Self, “Identifying bottlenecks and roadblocks in the rural mental health career pipeline,” Center for Rural Policy & Development, February 2023. https://www.ruralmn.org/identifying-bottlenecks-and-roadblocks-in-the-rural-mental-health-career-pipeline/

[26] “Minnesota Governor’s Task Force on Broadband 2024 Annual Report,” Minnesota Office of Broadband Development, p. 23, https://mn.gov/deed/assets/2024-broadband-task-force-report_tcm1045-664936.pdf

[27] Davies, Nicola. “Exploring the Value of Peer Support for Mental Health.” Psychiatry Advisor, May 20, 2024. https://www.psychiatryadvisor.com/features/exploring-the-value-of-peer-support-for-mental-health/

[28]Patrick Wade, “New Academy Trains Social Workers and Police Officers Together,” Public Safety, July 15, 2022, https://police.illinois.edu/new-academy-trains-social-workers-and-police-officers-together/.

[29]Morgan Poindexter et al., “Guest Commentary: Toward a New Model of Policing for Davis,” Davis Vanguard, September 1, 2020, https://davisvanguard.org/2020/09/guest-commentary-toward-a-new-model-of-policing-for-davis/. Esserman, Dean. “Co-Responder Models in Policing: Better Serving Communities.” National Policing Institute, August 27, 2021. https://www.policinginstitute.org/onpolicing/co-responder-models-in-policing-better-serving-communities/.

[30]Deanna Weniger, “As Law Enforcement Embeds Social Workers, Police See Positives, But Training Needed,” Police1, November 26, 2021, https://www.police1.com//mental-health-outreach/articles/as-law-enforcement-embeds-social-workers-police-see-positives-but-training-needed-0A22fZGKRh1hvCMK/.

[31]Esteban L. Hernandez, “What’s Next for the Police Response Alternative Star as It Turns Five,” AXIOS Denver, June 9, 2025, https://www.axios.com/local/denver/2025/06/09/whats-next-police-response-alternative-star.

[32]Danielle Cohen, “Here’s How a 911 Call without Police Could Work,” GQ, June 12, 2020, https://www.gq.com/story/how-a-911-call-without-police-could-work.

[33]Andrew Hay, “New Mexico Mental Health First Responders Are Increasingly Civilians, Not Police,” Reuters, April 16, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/new-mexico-mental-health-first-responders-are-increasingly-civilians-not-police-2024-04-06/.

[34]Sam Allard, “Cuyahoga County Eastern Suburbs to Collaborate on Crisis Response,” AXIOS Cleveland, May 8, 2024, https://www.axios.com/local/cleveland/2024/05/08/cuyahoga-county-eastern-suburbs-collaborate-crisis-response-first-call.

[35] Joseph P. Williams, “After Police Reform Defeat, Minneapolis Residents Still Seek Change,” U.S. News & World Report, December 2, 2021, https://www.usnews.com/news/health-news/articles/2021-12-02/after-police-reform-defeat-minneapolis-residents-still-seek-change.

[36] Berg-Weger, Marla, Thomas Cudjoe, and Yingying Lyu. Addressing the Impact of COVID-19 on Social Isolation and Loneliness. National Academies of Science, 2024. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27874/addressing-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-social-isolation-and-loneliness.

[37] Garcia-Navarro, Lulu. “Robert Putnam Knows Why You’re Lonely.” Magazine. The New York Times, July 13, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/13/magazine/robert-putnam-interview.html.

[38] “What is Men’s Shed?”, US Men’s Shed Association, https://www.usmenssheds.org/what-is-mens-shed.html

[39] “COMET: Changing our mental and emotional trajectory,” Unviersity of Minnesota Extension, https://extension.umn.edu/care-self-and-others/comet-changing-our-mental-and-emotional-trajectory

[40] “Social Determinants of Health.” World Health Organization. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1.