In the rolling farmland south of Rochester, Tom Rowekamp drives truck and works construction. In 2011, Rowekamp asked Dave Nisbit, a friend and farmer, about opening a sand mine on Nisbit’s land. Rowekamp would operate the mine and sell the sand for livestock bedding. Nisbit said, “Yes.” Winona County said, “Slow down.”

“If I had come in six or twelve months earlier, I’d have gotten a permit within weeks,” Rowekamp says. But increasing concern about the impact of silica sand mining for an oil drilling process called hydraulic fracturing spilled over onto Rowekamp’s proposal. “As soon as they attached [the mine proposal] to the oil companies, it brought out all the opposition.”

More than 300 miles away, in Minnesota’s boreal forest south of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, Ron Brodigan teaches people how to build log cabins and operates a resort. “I teach people who want to build their own homes,” says the owner of Snowshoe Country Lodge and Great Lakes School of Log Building. “The resort is a side business.”

In late 2011, Brodigan learned from a neighbor that the state of Minnesota, which owns the mineral rights beneath his resort, had sold 50-year mineral leases to two mining companies. The leases allow these companies to access Brodigan’s property to explore for copper, nickel, and other metals. “It’s been consuming our lives ever since,” Brodigan says.

Between Rowekamp and Brodigan, in a cluttered St. Paul office, sits Dennis Martin, the minerals potentials manager in the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Lands and Minerals. A 30-year veteran of the DNR, Martin picks up one of several drill core samples on his desk to illustrate a point, then walks to the map on his door to show the location.

When it comes to mining in Minnesota, location is critical, Martin says. Valuable minerals aren’t spread evenly or conveniently across the globe. “We can only mine where the minerals are.”

Minnesota is rich in minerals, most notably iron ore and taconite. Now it appears that we are also home to world-class deposits of copper, nickel, and silica sand.

Who is the “we” involved in minerals exploration? The we, it turns out, is everyone involved in the supply and demand of these minerals, including those who are caught—or place themselves—in the mix.

We the consumers are driving the demand for the gadgets that are in turn driving the demand for these minerals, especially our insatiable need for oil and for cell phones and other handheld devices. Those who own these valuable minerals, directly through property ownership or indirectly as shareholders in the companies that explore, mine, and market the minerals, stand to make a lot of money, if the initial exploration pans out and mining is permitted.

On the other hand, because mines are most often located in rural areas, rural Minnesotans like Rowekamp and Brodigan find themselves caught up in massive trends driven by global demand and advances in technology. Then there are those who work the mines, drive the trucks, manage the resorts, outfit the canoes, live with the noise, the dust, and the potential for pollution, the associations and activists who lead the never-ending debates, and the public officials, from township board members to the State Executive Council, who are charged with balancing our competing, conflicting, contradictory interests.

Ownership: Surface and mineral estates

When it comes to minerals and the land they’re found on, there are two types of property rights: “surface estate” and “mineral estate.” The surface estate is what people typically think of as a piece of property: defined by its dimensions and the things found within those dimensions, such as buildings and trees. Lying beneath the surface estate, though, is the mineral estate, encompassing the minerals found below the surface. The rights to the surface and mineral estates can be “severed,” bought, sold and leased independent of one another, according to Mineral Rights Ownership in Minnesota, a fact sheet published by the DNR.[i]

Policies regarding mineral rights ownership aren’t very specific. No uniform depth divides the surface from the minerals. The rights are defined by the original document severing the two estates. If the language is ambiguous—for example, our understanding of “all valuable minerals” may change over time—the courts will attempt to determine the original intent.

Mineral rights ownership hasn’t been directly addressed by the Minnesota Supreme Court, but under legal precedent it’s generally held that the rights of the mineral estate owner supersede the rights of the surface estate owner. Unless otherwise noted on the severance document, the DNR’s fact sheet on the subject says, “the mineral estate carries with it the right to use so much of the surface as may be reasonably necessary to reach and remove the minerals.”

Most Minnesotans aren’t concerned about severed mineral rights thanks to geology, historical settlement patterns, and public policy choices. When Minnesota became a state in 1858, the federal government granted millions of acres of land to the state government, railroads, and individuals, and put up for sale millions more acres. Lawmakers quickly sold holdings in southern Minnesota, where settlers and speculators saw valuable farmland, according to the DNR.[ii] Consequently, property owners in southern and central Minnesota typically own the minerals beneath their land.

That isn’t necessarily the case in northern Minnesota, where few people bought land until iron mining ramped up in the early 1880s. As ore poured out of the Iron Range, mining companies and speculators poured in, purchasing large tracts of land in St. Louis, Lake, and Cook counties. An 1889 law allowed the state to retain the mineral rights on land sales in those three counties. The law was expanded, though, eventually requiring the state to retain mineral rights on all of its property sales and transfers.[iii] Consequently, the state owns more acres of mineral rights than surface rights.

Private landowners also severed surface and mineral estates during the 1800s and 1900s. Over the decades, surface and mineral estates were bought, sold, leased, and divided through inheritance, but recordkeeping wasn’t always precise, making ownership difficult to determine at times.

Legislators attempted to clean up the mess in the 1970s by requiring severed mineral estate owners to claim ownership and pay an annual tax. Failure to do so forfeited the mineral rights to the state. Since then, more than half a million acres of mineral rights have been forfeit and are now managed in trust by the DNR. In addition, the state retains the mineral estate on any property forfeited anywhere in the state for failure to pay general property taxes. And because researching mineral ownership is only conducted on an as-needed, case-by-case basis, ownership remains unknown on millions of acres of land, according to the DNR.

Who owns—and who benefits from—Minnesota’s minerals?

The DNR estimates that about 70% of Minnesota’s mineral rights are privately held, primarily in the southern two-thirds of the state, where surface and mineral estates are less often severed. Among the private owners, mining companies own hundreds of thousands of acres. Large trusts and family estates with ownership dating back to the earliest prospectors and investors own thousands more. Some companies buy or lease mineral rights, then market them to the mining companies. [See sidebar: Minnesota Minerals.]

On the public side, the federal government owns 3.4 million acres of mineral rights, primarily in the Chippewa and Superior national forests. Native American tribes hold another 1.5 million acres.

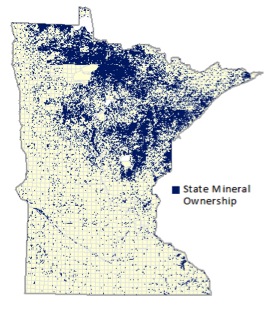

The single largest holder, however, is the state of Minnesota, with more than 12 million acres, over 20% of the state’s total area, including 2.5 million acres of land held in trust for Minnesota public schools. The DNR’s Division of Lands and Minerals manages the state’s mineral rights, as well as 25,840 acres of permanent university fund lands and an additional 21,373 acres of mineral rights owned outright by the University of Minnesota.[iv]

Minnesota’s policy, according to state statute, is to support “mineral exploration, evaluation, environmental research, development, production, and commercialization.” Consistent with this, the DNR leases out the rights to some of the state’s surface and mineral holdings for mining metallic and industrial minerals, construction aggregates, and peat.

“The minerals belong to the people of Minnesota,” says Martin. “My job is to convert the land asset into money for schools.” Cities, counties, and public agencies also benefit from these leases.

State mineral leases generate a considerable amount of money for the state: $198 million between fiscal years 2002 and 2011. These funds benefit public schools, the University of Minnesota, and the counties in which the property is located,[1] according to Revenue Received from State Mineral Leases, 1890-2011, Annual Report. [v]

Beyond rents and royalties, mining companies also pay state taxes, which totaled nearly $128 million in FY11, according to the Mining Tax Guide produced by Minnesota Revenue. The Taconite Production Tax raised $80 million for schools, counties, cities, and townships within the Taconite Assistance Area, as well as the Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation Board, the region’s economic development agency.[2]

Three other taxes—the occupation tax, a form of corporate income tax; the state sales and use tax; and an income tax withholding on royalties—generated $47.1 million, allocated to the state’s general fund, K-12 education, and the University of Minnesota. [vi]

Royalties from construction aggregate on school trust land generated $2.7 million during FY02-FY11.[vii] There are no statewide taxes specific to aggregate, but 35 counties imposed an aggregate production tax, collecting $5.7 million in FY11, according to House Research at the Minnesota Legislature.[viii]

Mining opponents point out that large multinational companies profit the most when it comes to selling Minnesota’s minerals. [See sidebar: Juniors and Majors.] “There is a growing awareness that some very large corporations, oil companies in particular, are profiting at the expense of the rest of us and the environment,” says Bobby King, a policy program organizer with the Land Stewardship Project. “That makes people angry.”

Scratching the surface

Every county has at least one aggregate mine—or gravel pit—where bulldozers and backhoes dig sand, gravel, and crushed stone used in construction and everyday products like glass, pottery, abrasives, semiconductors, and solar cells, according to the Aggregate and Ready Mix Association of Minnesota (ARM).

Nonmetallic minerals found on or near the surface are part of the surface estate. While rights to surface minerals may be severed, in the case of nonmetallic minerals, property owners typically choose to lease the land to mining operations. Different operators may mine the same tract of land simultaneously or at different times over the life of the mine.

Aggregate mines are usually small, locally owned and operated. “But the trend has been toward consolidation in operations, because there is significant capital involved,” says Fred Corrigan, ARM executive director.

Depending on their scope or location, aggregate mines may need state or federal permits. But counties, townships, and cities are the primary regulators—and often the largest customers. Aggregate is an essential component for road maintenance and construction. Heavy and expensive to haul, most aggregate is used locally.

Counties set the baseline for regulation. Zoning ordinances and land use permits balance the rights of property owners, neighbors and taxpayers by regulating conditions like location, setbacks, operating hours, noise levels, water use, and truck traffic. Counties may collect taxes and fees to offset additional public expenses. Townships and municipalities may impose additional restrictions and fees, but cannot issues permits that are less restrictive than the county’s.

Local control creates a patchwork of rules and standards that may at times seem arbitrarily applied. It can also create friction when a city or township imposes, or refuses to impose, stricter standards, says Kent Sulem, an attorney with the Minnesota Association of Townships.

From Ortonville on Minnesota’s western border to St. Charles in the southeast corner, cities and townships have been swept recently into annexation fights as property owners and sand processors seek more favorable jurisdictions. Sulem says cities have the upper hand in these arguments, because they control if and when to initiate annexation and whether to go to court if a township objects.

“Property rights are always sticky issues, because what I do with my land may impact what you do with yours,” Sulem says. “Zoning is something people want done to their neighbors, not themselves.”

Super sand

Tom Rowekamp’s permit request to operate a 19-acre sand mine on Dave Nisbit’s property—normally a run-of-the-mill county board decision—ran headlong into a national debate about hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. The drilling technique pumps water, chemicals, and a proppant under high pressure into wells, breaking the shale rock. The proppant holds the shale fractures open, allowing the trapped oil and natural gas to escape. The silica sand found in large swaths of land from northern Illinois to southeastern Minnesota is nearly pure quartz, very hard, strong, and smooth—making it some of the best frac sand in the world.

(Google Maps)

Silica sand also makes great livestock bedding, because it’s less abrasive than other sand, holds less bacteria than sawdust, and is easier to clean, says Rowekamp. “It’s not frac sand,” he insists. “It’s industrial sand. Until it gets to an oil field. Then it’s frac sand.”

Fracking made oil booms possible on shale fields in Pennsylvania, North Dakota, and Texas, and created a sand boom in Wisconsin. That boom has yet to hit Minnesota, where there are fewer than 10 active silica mines and minimal frac sand sales. But interest is building.

For some, frac sand is just a symbol of a bigger debate. The prospect of reducing U.S. dependence on foreign oil creates support for frac sand mining among some, while continued reliance on oil and gas draws opposition from others. For local officials, however, silica sand mining decisions are parochial and pragmatic. Sand sold for fracking can be as much as five times more profitable for the owner than the same sand sold for other purposes, Rowekamp says. Frac sand mines also tend to be larger and operate at higher capacity than traditional aggregate mines, creating more jobs in excavating, transporting, and processing.

It’s the potential for dramatically increased activity that separates frac sand from aggregate or industrial sand mining. Several southeastern Minnesota counties imposed temporary moratoria on silica sand mining in 2011 and 2012 to provide more time to study these issues. In Winona County, where the Nisbit mine is located, engineers say the roads are designed to handle heavy truckloads from agriculture, manufacturing, and aggregate mining—but not at the heavy volumes associated with frac sand. County engineers calculated that a frac sand mine running 130 truckloads a day, six days a week would crush the expected life span of a road reconstruction project from 20 years down to as little as two years.[ix]

One option available to counties is to impose a production tax on aggregate. But state law dictates how that revenue would be distributed.[3] Rather than tax aggregate, Winona County, when it lifted the moratorium on silica sand mining in 2012, imposed a 22.5-cent per-ton, per-mile fee on sand sold for fracking, but not for other uses. This disproportionate user fee enables the county to collect revenue from a specific project and requires the county to direct the revenue to offset the impact of that project, explains Jason Gilman, Winona County director of planning and environmental services. “Our task is to make it as fair as possible,” he says.

While several silica sand mines have been proposed in the area, the Nisbit mine is the first to be approved. The mine, which opened in October 2013, isn’t currently selling sand for fracking, but that could change. Rowekamp doesn’t take issue with the three dozen conditions placed on the mine. But the road-use fee seems heavy. “I’m not sure why I have to completely pay for redoing the road,” he says.

The State Legislature steps in

Opponents point to other potential impacts of frac sand mining besides damage to roads and bridges. A report by the Land Stewardship project compiled people’s concerns about the effects of silica dust and diesel fumes on people and livestock; the potential for water pollution to spread quickly through southeastern Minnesota’s caves and crevices, called karst formations; the impact that pumping large volumes of water can have on groundwater levels and area wells; and the possible damage to tourism and property values.[x]

State lawmakers stepped into the fray in 2013, passing legislation that applies only to the southeastern corner of the state, called the “driftless” area. The law prohibits silica sand mining—but not aggregate mining—within one mile of a trout stream without first receiving a permit from the DNR.

The law also reduces thresholds triggering a mandatory Environmental Assessment Worksheet (EAW) for silica sand mines and storage facilities approved between July 2013 and July 2015. The EAW requirements include an assessment of existing water resources, a project’s impact on those resources, and mitigation plans.

In addition, state agencies adopted an air quality value for silica sand dust, approved rules to control silica sand dust, and created rules for reclaiming silica sand mines.

Lawmakers also directed the Environmental Quality Board to assist local decision-making by creating a library of local government ordinances and approved permits; assembling a silica sand technical assistance team; and developing model standards for mining, processing and transporting silica sand.

The initial draft of the model standards, released in September 2013, was widely panned, confirming the challenge of even suggesting standards for areas as diverse as the bluff country and the Minnesota River valley. But local officials appreciated other aspects of the law.

“We don’t need mandates,” says Sulem at the township association. “We do need guidance, support, access to expertise.”

“I like that they focused on issues like air quality that transcend jurisdictional lines,” Gilman says. “Most counties don’t have the expertise that the state has.”

But industry representatives are troubled by what they see as a double standard. “It’s the same equipment, the same processes,” says Mike Caron, director of land use affairs at Tiller Corporation. “It’s like telling a farmer that if you’re selling corn for cornflakes, you’re OK. But if you’re selling corn for ethanol, you’re not.”[4]

What lies beneath

When Ron Brodigan moved his school for log cabin building from Hinckley to a resort near Isabella in 1977, he knew he’d bought the land but not the minerals beneath it. More than 20 miles from the edge of the Mesabi Range, however, Brodigan wasn’t concerned. Mining at the time was contracting, not expanding.

For more than a century, the Iron Range—the Vermilion, Mesabi, and Cuyuna ranges—produced 75% of the ore mined in the United States, according to the Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation Board (IRRRB), a state agency focused on economic development in northeastern Minnesota. But the ore was nearly gone by the late 1970s.

Then University of Minnesota researchers developed the technology to extract the iron ore from taconite. Once considered waste rock, taconite became profitable, and the Range recovered. Today, Minnesota mining is booming again. With six active taconite operations producing 40 million tons of taconite a year,[xi] Minnesota still turns out about 75% of the United States’ total iron ore production.[xii] In addition, 18 new projects and expansions are under development.[xiii]

Regionally, mining still represents around 30% of the Arrowhead’s economy, more than tourism (11%) and forestry (10%) combined, according to a study by the Labovitz School of Business and Economics at the University of Minnesota, Duluth. The study estimates that 4,150 jobs were directly involved in mining in 2010 with 7,600 spinoff jobs.[xiv]

New fault lines in old bedrock

It’s the prospect of nonferrous—or not iron—mining that excites supporters but keeps its detractors awake at night. “When rain falls on the waste from iron mining, it makes rust,” reads the Friends of the Boundary Waters Wilderness sulfide mining page. “When rain falls on sulfide ore waste, sulfuric acid is produced.” [xv]

In 1948 geologists found copper, nickel, platinum, and other valuable metals locked up in the northern Minnesota bedrock. These metals are essential for everyday activities like turning on a light, turning on the water, talking on a cell phone, and sending an email. But the copper-nickel concentrations were too low for the available technology to allow cost-effective mining in Minnesota.

The economics and technology have changed, however. Growing global demand for base metals like copper, nickel, lead, zinc, and titanium and precious metals like gold, silver, and platinum makes Minnesota’s estimated 4.4 billion tons of nonferrous metals increasingly valuable. New hydrometallurgical processes can separate the metals from the sulfide. And the opportunity to reuse a closed taconite plant and existing rail lines reduce capital costs.

While there are 10 active state and federal leases for nonferrous mining in northern Minnesota, there is, as yet, no nonferrous mining in the state. After more than a decade of planning, the NorthMet open pit project proposed by PolyMet is furthest along. The proposal covers 16,700 acres of privately held mineral rights beneath an unmined section of the Superior National Forest near Ely and Babbitt. The ore would be processed at the shuttered taconite plant outside Hoyt Lakes. Open pit mining isn’t allowed in the national forest, so PolyMet is pursuing a land exchange with the U.S. Forest Service.

Twin Metals, a proposed 32,000-acre underground mine on federal, state, and private property east of Babbitt, is the largest nonferrous proposal to date. After more than five years, the company expects to release a feasibility study in 2014, which will trigger the multi-year environmental review process.

If all the proposed ferrous and nonferrous projects are implemented, the Labovitz report estimates, the total economic impact of mining in the region would grow to $7.8 billion, up from $3.2 billion in 2010. Direct mining employment would more than double to 9,600. Total employment attributable to mining could exceed 27,000.[xvi] Tax, lease, and royalty revenue would increase proportionately. The DNR estimates that nonferrous rents and royalties alone could raise between $1 billion and $2 billion over the next 20 years.

Opponents, however, challenge the economic benefits of mining. In 2007, Thomas Power, an economics professor at the University of Montana, analyzed the decline in mining jobs in the region over the previous 25 years against overall increases in per-capita income. “As a result of declines in the iron industry and expansion of the rest of the economy, the relative importance of the iron industry as a source of income and jobs declined dramatically,” the report states.[xvii]

Although employment is likely to increase with nonferrous mining, the report contends that mining employment won’t return to peak levels and questioned the impact of a few thousand jobs in a regional economy with a total employment at the time of 152,000 people.[xviii]

A Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement on the NorthMet project, released in December 2013, launched a 90-day public comment period. Environmental groups warn that any economic benefits of sulfide mining—their preferred term—come at a high cost. They point to a long history of environmental damage around the world caused by sulfuric acid leaching heavy metals and chemicals into lakes, rivers, and groundwater. In northern Minnesota, the affected areas could include the BWCA, Lake Superior, countless other lakes, rivers, and streams—and the tourism industry that depends on those resources. The environmental analysis estimates that water from the site will have to be treated for hundreds of years following the mine’s closure, raising concerns about the mine’s operation and long-term financial assurances to protect the environment and Minnesota taxpayers. Mining supporters point to Minnesota’s strong environmental laws and the industry’s commitment to new, more environmentally friendly technologies. “Minnesota is known for being a state that takes big issues seriously and does things right,” says Tony Sertich, commissioner of the IRRRB. “Companies will not get permits if they can’t meet Minnesota standards. But if they can meet our standards, we should move forward.”

But Kathryn Hoffman, an attorney with the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy, isn’t convinced. Pointing to expired permits, permit violations, and variances in taconite mining, Hoffman says, “Minnesota has strong environmental laws and applicable federal laws, but those laws are only as good as their enforcement.”

You want to dig on my property?

For more than 40 years, nonferrous lease sales by the DNR attracted bids from mining companies, but drew little public attention—for good reasons. Lease sales are a mundane process. [See sidebar: An Overview of Mineral Lease Sales.] The pool of eligible bidders is small. In most cases, the state owns both the surface and mineral estates. And lease sales rarely lead to exploration, let alone discovery of mineable minerals.

(Google Maps)

Public attention to lease sales surged in 2011, however. It was at this time that Ron Brodigan learned the DNR had leased out the mineral rights beneath his resort to a pair of mining companies, Duluth Metals and Encampment. Surprised and angry, Brodigan and others affected by the sales complained about the process to the State Executive Committee—the governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, secretary of state, and state auditor—which approves the leases. The committee delayed but eventually approved the sale of the leases.

A second group of property owners challenged state lease sales in 2012, this time arguing in court that the DNR should complete an Environmental Assessment Worksheet prior to any lease sale. The DNR argued that such assessments aren’t applicable because there are no specific proposals to assess and that exploration alone causes no significant environmental damage. Landowners lost in the district and appeals courts but have appealed to the State Supreme Court. Again, the Executive Committee delayed but ultimately approved the lease sales.

The DNR’s Martin says landowner concerns and objections are based on a misconception about mineral leasing, exploring, and mining. A lease, he says, gives the holder permission to look for minerals—but not mine them. Actual mining requires environmental reviews along with federal, state, and local permitting that take years to complete.

Further, Martin says, mining companies may lease large areas of land but conduct physical exploration on a fraction of their holdings. Companies take surface samples from about one-fifth of the parcels leased in Minnesota and drill exploratory holes on less than 3%, according to DNR statistics.[xix] Exploratory drilling has picked up, however, with 24% of all drill holes since 1966 occurring in the past five years.

Despite the increase in exploration, though, leases rarely pan out. Nearly 90% of the time, leaseholders allow their leases to lapse within a few years of purchase, according to the DNR. More than 99% of all nonferrous leases sold on state land since 1966 have lapsed within 10 years of purchase.

Those statistics don’t comfort Brodigan, who says he’s disgusted by the thought of mining companies prospecting and potentially mining in the area, mixing the drone of heavy equipment and bedrock drills with the sound of the lake and the woods. “Who in their right mind would want to come here if that’s going on?” he asked.

Mineral estate owners have the right to access their property, but also the obligation to compensate surface owners for loss of surface rights or damages. “We try to minimize our impact and work with property owners in the area,” says Phil Larson, senior geologist with Duluth Metals.

If a mining company and surface owner can’t agree on compensation, the company can ask the state attorney general to condemn the property with approval from the commissioner of natural resources. Minnesota has never exercised eminent domain for a mining interest. Not yet, anyway, Brodigan cautions. “Neither company has come and asked to drill,” he says. “When they do, I expect most of us will say ‘no.’”

“I can’t think of a case when we asked permission and were told to go away,” Larson says. “The law exists to help the sides come to a reasonable agreement. If you deprive someone of access to their [mineral estate], that’s a taking as well.”

Conclusion

From the Arrowhead to the Bluffs Region, “We need a conversation” is a phrase often heard in relation to mining. The specifics are different. The people are different. But the topic inevitably boils down to who owns Minnesota’s minerals, who holds the rights and responsibilities of ownership, and how we decide what to do with our mineral wealth.

Those conversations are already taking place. As Sertich at the IRRRB says, “We’ve been living this conversation for generations.” Nevertheless, the phrase “We need a conversation” suggests that we are far from finding a balance in our competing, conflicting, contradictory interests.

— Tom Teigen is a freelance writer from St. Paul

Footnotes & Endnotes

[1] From 2002 through 2011, leases on permanent school trust lands earned $120 million, which was deposited into the Permanent School Fund. University of Minnesota lands generated $65 million for the University. Various other categories of state-owned property earned the remaining $13 million, with most of the revenue distributed to the host counties.

[2] In 2011, revenue from the taconite production tax was distributed to a variety of entities: Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation Board, $17.9 million; school districts, $15.6 million; counties, $13.3 million; property tax relief, $12.8 million; cities and townships, $10.4 million; the Taconite Economic Development Fund, $10 million; and the Range Association of Municipalities and Schools, $110,000.

[3] The county can retain up to 5% for administration; 100% of the remainder is divided among the host township (42.5%); the county roads and bridge fund (42.5%); and a reserve fund for abandoned pit reclamation (15%).

[4] The Environmental Quality Board issued a revised draft of the model standards in mid-December. Tools to Assist Local Governments in Planning for and Regulating Silica Sand Projects is available at http://www.eqb.state.mn.us/. The nearly 170-page document provides “information and recommendations related to a number of issues, including such things as water quality, natural vegetation and wildlife habitat, air quality and transportation,” according to the EQB website.

[i] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Lands and Minerals. (November 2000.) Mineral Rights Ownership in Minnesota.

[ii] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Lands and Minerals. (May 2000.) Public Land and Mineral Ownership in Minnesota: A Guide for Teachers. Page 15.

[iii] Ibid. Page 23.

[iv] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Minnesota’s Permanent University Land and Fund.

[v] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Lands and Minerals. (April 2012.) Revenue Received from State Mineral Leases, 1890-2011, Annual Report. Page 8.

[vi] Minnesota Revenue. (December 2012.) Mining Tax Guide. Inside cover & Page 2.

[vii] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Lands and Minerals. Data accessed at http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/aboutdnr/school_lands/revenue/aggregate.html. Used only data from FY02-FY11 to coincide with similar data from metallic mineral leases.

[viii] House Research. (August 2013.) Short Subjects: Aggregate Tax.

[ix] Department of Public Works, Winona County. (February 2012.) Sand Mining Road Impacts. Slide 30.

[x] Land Stewardship Project. (September 2013.) The People’s EIS Scoping Report.

[xi] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Lands and Minerals. (February 2013.) Iron Mining on the Mesabi Range: Taconite and Iron Ore Mine Lands.

[xii] Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation Board. (March 2013.) Explore Minnesota: Iron Ore

[xiii] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Lands and Minerals. (February 2013.) 2012/2013 Mineral Development and Exploration Highlights.

[xiv] University of Minnesota Duluth, Labovitz School of Business and Economics. (November 2012.) The Economic Impact of Ferrous and Nonferrous Mining on the State of Minnesota and the Arrowhead Region, including Douglas County, Wisconsin. Pages 4 & 27.

[xv] Friends of the Boundary Waters Wilderness. Sulfide Mining page. Accessed November 2013 at http://www.friends-bwca.org/issues/sulfide-mining/.

[xvi] Ibid. Page 32.

[xvii] Power, Thomas Michael, Economics Department, University of Montana. (October 2007.) The Economic Role of Metal Mining in Minnesota: Past, Present, and Future, A report prepared for the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy and the Sierra Club. Pages III.

[xviii] Ibid. Page 21.

[xix] Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Lands and Minerals. Data accessed October 2013 at http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/lands_minerals/metallic_nf/leasing.html#F.