Public transit is important to all communities across the state, but the form it takes and who uses it varies a lot depending on location. This article and the accompanying fact look at the top things to know about public transit in Minnesota, including who operates it, how it’s funded, and most importantly, who uses it and why.

Rural Reality: City Transit, Rural Transit | Click to download the pdf

City transit, rural transit

January 2016

There is no law requiring any entity to provide public transportation, but it is such a vital service, most communities work hard to offer it in some form. We are a society in motion, and in both the Twin Cities and Greater Minnesota, public transportation keeps the wheels of commerce turning by getting hundreds of thousands of people to work, school, services, shopping, and health care, particularly those people who cannot drive or do not own a car.

In 2014, public transit systems provided 12 million rides in Greater Minnesota and almost 98 million rides in the Twin Cities. That number is only expected to grow in the coming years as the elderly population doubles in both the Twin Cities and Greater Minnesota. Added to that, a 2015 court decision has raised the importance of public transportation by ensuring people with disabilities the right of access to jobs, health care, shopping, and other aspects of independent living.

What are key items to know about public transportation in Minnesota at the start of 2016?

- Public transportation/transit is more than light rail: While light rail has received most of the attention in the news lately, it makes up only part of the state’s transit system. Of the 110 million rides taken in Minnesota in 2014, nearly three quarters of them were on a bus. [1]

- We have a transit-dependent population: Right now, 52% of Twin Cities bus riders reported not having a working car. In 2010, a little over 50% of transit riders in Greater Minnesota reported not having either a car or a driver’s license. That share rose to 70% for small rural systems.[2] The number of “transit-dependent” people is only expected to grow as the senior population is expected to double over the next 20 years.

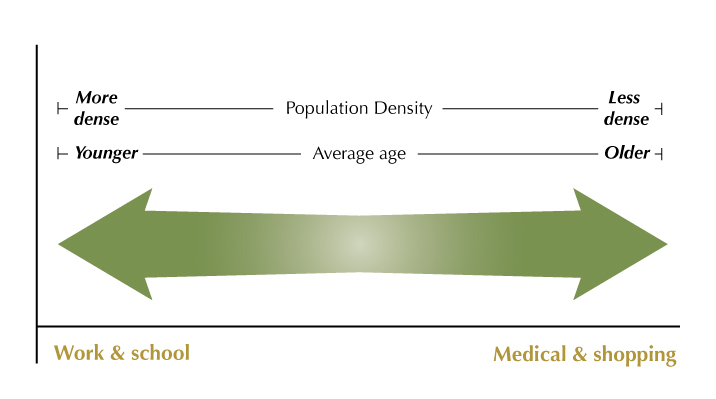

- Transit is used by different audiences in different places: While about three fourths of riders in the Twin Cities and the state’s other large cities are commuters, riding to work or school, in smaller communities and rural areas, that share of riders goes down while the ridership for seniors and persons with disabilities goes up.

- Getting along: The trend with rural systems right now is to merge into multi-county systems for greater efficiency and cost savings, but there are policies in place that can create problems, including barriers to coordination between the transit service and county human and family services agencies, especially when it comes to operating across county lines.

- New mandates: In 2015 the courts approved a plan for the state of Minnesota to comply with the Supreme Court decision of Olmstead v. L.C., which requires that government entities do not discriminate against persons with disabilities by denying them opportunities to live and work in the most integrated environments possible that are still appropriate to their needs. Public transportation plays a fundamental role in this decision.

Just what is public transportation?

Public transportation is a good example of a “public good,” a service the government and the people believe is important enough to be provided regardless of whether it pays for itself or not, like roads and national defense. In 2013, Minnesotans used buses, paratransit, trains, and vanpools to take nearly 107 million rides somewhere in the state.

Public transportation comes in several different forms in the Twin Cities, where the Metropolitan Council regional government operates an extensive network of buses, Metro Mobility mini buses for seniors and the disabled, the Northstar commuter train line, and two light rail lines.

In Greater Minnesota, public transportation comes in the form of local and regional transit systems operated by dozens of county and city governments, joint powers agreements, community action programs, and nonprofits, staffed by both paid workers and volunteers and using buses, vans, and cars.

Who uses public transportation?

Four types of riders commonly use public transportation in Minnesota:

- Workers and students. A majority of riders in the Twin Cities (about 75%) use the Metro Transit system for going to work or school, according to a 2014 ridership survey conducted by Metro Transit, the public transportation division of the Metropolitan Council.[3] More than half of riders (54%) do the same in Greater Minnesota, says an on-board rider survey conducted by the Minnesota Department of Transportation in 2010.[4]

- Seniors. As people age and abilities like reflexes and eyesight fade, seniors can get to a point where they don’t feel comfortable driving themselves even a short distance. However, they still need to get to shopping and health care appointments.

- People with disabilities that prevent them from driving or affording a car need to access groceries and health care, too. Many seniors fall into this category as well; for that reason the number of persons with disabilities is expected to go up as the senior population grows. A Metropolitan Council report projected that, in the Twin Cities, the population of people with disabilities will grow anywhere between 36% and 92% by 2030.[5]

- Low-income. Accessing a reliable car is always a major challenge for low-income people. Many depend on transit to get to work, shopping, health care, and anywhere else farther than walking distance.

While ridership in the Twin Cities is very commuter-heavy, the mix varies quite a bit in Greater Minnesota, depending on population density and demographics. For example, in MnDOT’s 2010 on-board rider survey, 16% of respondents overall identified themselves as 65 or older, while only 3.8% did so in the large urban fixed route systems (e.g., Duluth, St. Cloud, Rochester). The number of senior riders rose to almost 32% for rural transit systems. (Transit systems in Greater Minnesota are designated either “large urban fixed route systems,” “small urban transit systems,” or “rural transit systems” depending on the population density of the area the system covers.) On the flip side, 52% of riders in large urban fixed route systems reported themselves as being age 18-34, but that number dropped to 22% for small urban systems and 18% for rural systems.[6]

What is “transit dependence”?

Much of whether a person uses public transportation has to do with whether he or she has a car or has the ability to drive one. When public transportation is a person’s only option for getting to work, groceries, or medical appointments, that person is “transit-dependent.”

In the larger communities in Greater Minnesota, ridership is spread fairly evenly among workers and students (both college and school-age), seniors, and persons with disabilities, but in very rural Minnesota, seniors and people with disabilities become the primary users, said Tom Gottfried, program director at MnDOT’s Office of Transit.

About half of respondents (51%) in MnDOT’s 2010 Greater Minnesota ridership survey said they did not have a driver’s license, and 53% said they were riding because they didn’t have a car or didn’t drive. When responses were broken down by the size of community, however, the percentages changed considerably. In smaller, less dense population areas, access to public transportation is more of a need than a choice.

Riders of small urban systems and rural systems were more likely to be older than the total Greater Minnesota average, were more likely to ride for shopping and medical appointments, and were less likely to have a car or a driver’s license. Riders of large urban route systems in Greater Minnesota tended to be younger than the survey’s statewide average, rode more often, and were more likely to ride to work or school. They were also more likely to own a car or have a driver’s license, but they still chose to use public transportation even though they had the option of driving. Interestingly, the latest survey by Metro Transit of Twin Cities riders found that 25% said one of the reasons they rode transit was because they “prefer a car-free lifestyle.”[7]

Income is also a major factor. In all parts of the state, accessing a reliable car is always a significant challenge for low-income people, and therefore public transit becomes critical. Nearly two thirds of respondents (62%) in the Greater Minnesota rider survey reported household incomes of less than $20,000. Likewise, in the Twin Cities urban core, 47% of bus riders and 34% of light rail riders reported having incomes of less than $25,000, according to Metro Transit’s 2014 transit rider survey.

How is public transportation funded?

There are three primary ways to fund public transportation:

- Customers pay fares in the form of cash, passes and punch cards.

- Public funding from federal, state, and local governments goes toward both operating and capital expenditures. The federal government is a major funder of capital expenses (buses, bus garages, and other equipment) for all types of transit systems, while the state puts in only a small percentage. On the operating expense side, the state puts in a much larger share than the federal government, but the federal government also provides support for service areas outside of large urban areas, for the intercity bus system, and for reverse commuting programs. The local government share is about the same for both types of expenses.[8]

- A portion of transit is also funded through reimbursements from county human services, family services, Developmental Achievement Centers, and health insurance for people receiving public assistance (seniors, low-income people, and people with disabilities).

A policy issue: Coordinating services

One policy barrier Greater Minnesota transit systems have been working to overcome has been making it easier to move passengers from one transit system area to another. Whereas public transit in the Twin Cities, including paratransit for the elderly and disabled, is managed by one agency, Metro Transit, public transportation in Greater Minnesota is a patchwork of many small, independently operated systems working side by side. These systems may or may not connect smoothly to each other, says the 2014 annual report[9] from the Minnesota Council on Transportation Access (MCOTA), a partnership among several state agencies that was created by the Minnesota Legislature in 2010 to help improve the coordination, accessibility and cost-effectiveness of the state’s transportation services. This is especially an issue in Greater Minnesota, where a person may have to travel 30 miles or more to a clinic appointment or the grocery store, crossing from one transit territory into another. Who is responsible for the cost of taking that passenger to his or her destination, and who is responsible for bringing that person back?

The problem has been partly taken care of by merging transit systems, thereby increasing the area covered by a single system. For example, Paul Bunyan Transit, covering Beltrami County and the city of Bemidji, merged in early 2015 with Far North Transit, serving Roseau and Lake of the Woods counties.

Despite mergers, though, the issue remains and stands out in one area in particular: subsidized rides.

The relationship between rural transit systems and human services is perhaps not well understood by people who aren’t directly involved, but it is important since it provides a vital link for seniors, the disabled, and low-income residents. Because of the strict requirements for confidentiality, sharing the information necessary to coordinate ride schedules has been problematic for county human services and similar entities, especially across county lines, according to a 2012 report by MCOTA.[10] Some entities have adapted better than others.

Arrangements with public services can vary from one transit system to the next, said Ted Nelson, transportation program manager for Prairie Five Rides, a part of Prairie Five Community Action Council Inc., serving Big Stone, Chippewa, Lac Qui Parle, Swift, and Yellow Medicine counties in western Minnesota. The public transportation system operates 20 accessible buses and vans driven by more than 20 paid drivers, plus coordinates 30-40 volunteers driving their own cars.

As an example of how ride coordination works, Prairie Five Rides has contracts with all five county human services/family services agencies, plus two insurance companies, and local developmental achievement centers. Clients of these agencies make appointments for rides through their agency/insurance provider/DAC. Those agencies contact Prairie Five Ride’s dispatch office with the list of appointments, and the dispatchers assign a schedule for the drivers. After the rides are completed, Prairie Five Rides reimburses the volunteer drivers at the federal mileage rate (currently 57.5 cents a mile). The appropriate agencies are invoiced monthly for mileage and an administrative fee.

Because of the long distances involved in getting around rural areas, being able to coordinate riders’ schedules is key to keeping buses and cars running on the most efficient schedule possible, thereby getting the maximum number of people to where they need to go on any given day.

“In most cases our distances are over forty miles, and we are not always able to put more than one person in a vehicle,” Nelson said. “We do the best we can.”

Another policy issue: The Olmstead Plan

With the growing number of disabled riders comes an additional new policy challenge: upholding the requirements of Minnesota’s Olmstead Plan. In 1999, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Olmstead v. L.C. that people with disabilities cannot be prevented from living, learning, or working in the most integrated setting appropriate to their needs, essentially reinforcing the Americans with Disabilities Act.[11] A suit was brought against the state of Minnesota in 2011 based on the Olmstead decision; in response, the state agreed to develop an “Olmstead Plan” that would expand opportunities for people with disabilities.[12] That plan was approved by the U.S. District Court in September 2015.

Transportation will be a critical element that ties into all parts of the plan. “A person’s ability to get to work, medical appointments, shopping, and social connections is key to independent living,” MCOTA’s 2014 annual report states.[13] The vision statement for the transportation portion of the Olmstead Plan lays out the important role transportation plays in meeting the requirements of the Olmstead decision and the Americans with Disabilities Act: “People with disabilities will have access to reliable, cost-effective, and accessible transportation choices that support the essential elements of life such as employment, housing, education, and social connections. They will have increased access to transit options and transportation modes.”[14]

The Olmstead Plan contains four goals for transportation:

- Making accessibility improvements to 4,200 curb ramps and 250 accessible pedestrian signals on MnDOT right-of-ways by Dec. 31, 2020, and by Jan. 31, 2016, have a target established for sidewalk improvements.

- Expand transit service in Greater Minnesota through additional rides and service hours so that by 2025 the annual number of passenger trips will have increased to 18.8 million (an increase of approximately 50%).

- Expand transit coverage so that by 2020 at least 90% of the public transportation service areas in Minnesota will meet minimum service guidelines for access.

- Get the on-time performance of transit systems statewide to 90% or better.

Meeting the first goal will depend on where and when MnDOT road projects are scheduled, which will in turn depend on MnDOT’s budget, since these improvements will only be made as part of larger projects.

Applying the rest of the goals, however, will likely fall disproportionately on small urban and rural transit systems. According to MnDOT’s 2010 rider survey, riders in small urban and rural transit systems said the enhancements they would like most to see would be longer hours of service and service on more days.[15] These are often the systems where transit-dependent riders have fewer options, and longer distances and travel times make on-time service difficult. In addition, transit providers themselves have a harder time finding staff and the funding to expand services.

While public transportation faces challenges across the state, it is a vital infrastructure that keeps people and commerce moving throughout the state and adds to the livability of every community. With the prospect of a growing transit-dependent population in both Greater Minnesota and the Twin Cities, both maintenance and innovation will be needed to keep those wheels turning.

Recommendations

As the legislature discusses public transportation, here are a few things to be aware of:

- Keep in mind that public transportation is more than light rail. Don’t let the entire conversation be overtaken by one comparatively small issue to exclusion of everything else.

- Plan accordingly for the projected increase in a transit-dependent population. Already, a large segment of the population would be stranded without public transportation. This transit-dependent population is only going to get bigger as the number of seniors and people with disabilities grows over the next twenty years.

- Because of the Olmstead decision and court settlement with the state, the planned upgrades to accessibility in transit systems are not optional, and much of the work will probably fall on transit systems. Aside from that, though, these upgrades will make it easier for an entire growing segment of the population to get around and contribute to their communities and the state overall.

[1] Minnesota Department of Transportation, “2014 Transit Report: A Guide to Minnesota’s Public Transit Systems,” February 2015.

[2] Minnesota Department of Transportation, “Greater Minnesota Transit Investment Plan 2010 On-Board Survey Tech Memo,” August 2010.

[3] Metropolitan Council, “Transit rider survey shows high customer satisfaction,” April 30, 2015.

[4] Minnesota Department of Transportation, “Greater Minnesota Transit Investment Plan 2010 On-Board Survey Tech Memo,” August 2010.

[5] Metropolitan Council, “2014 Performance Evaluation Report,” April 2015.

[6] Minnesota Department of Transportation, “Greater Minnesota Transit Investment Plan 2010 On-Board Survey Tech Memo,” August 2010.

[7] Metropolitan Council, “Transit rider survey shows high customer satisfaction,” April 30, 2015.

[8] Minnesota Department of Transportation, “2014 Transit Report: A Guide to Minnesota’s Public Transit Systems,” February 2015.

[9] Minnesota Council on Transportation Access, “2014 Report on the Minnesota Council on Transportation Access,” January 2015.

[10] Minnesota Council on Transportation Access, “Planning for Enhanced Transportation Access and Efficiency,” April 2012.

[11] Minnesota Department of Human Services, “Minnesota’s Olmstead Plan.”

[12] Minnesota Council on Transportation Access, “2014 Report on the Minnesota Council on Transportation Access,” January 2015.

[13] Minnesota Council on Transportation Access, “2014 Report on the Minnesota Council on Transportation Access,” January 2015.

[14] Minnesota Department of Human Services, “Putting the Promise of Olmstead into Practice: Minnesota’s Olmstead Plan,” August 2015, page 64.

[15] Minnesota Department of Transportation, “Greater Minnesota Transit Investment Plan 2010 On-Board Survey Tech Memo,” August 2010.